Britain’s biggest cities were the slowest to recover after lockdowns. But does this mean that they face greater long-term challenges? Not necessarily, says Valentine Quinio (Centre for Cities).

While some high streets up and down the country were already facing tough challenges before the pandemic hit, none of them were spared by the COVID crisis. The “stay-at-home” orders last spring, now reintroduced, have triggered an unprecedented hollowing-out of our city centres. But what happened when restrictions were released?

In order to track the recovery of the UK’s 63 largest city centres, the Centre for Cities has monitored footfall, using near real-time anonymised mobile phone data. What it showed is that throughout the different phases of the crisis, city centres have coped very differently with the pandemic

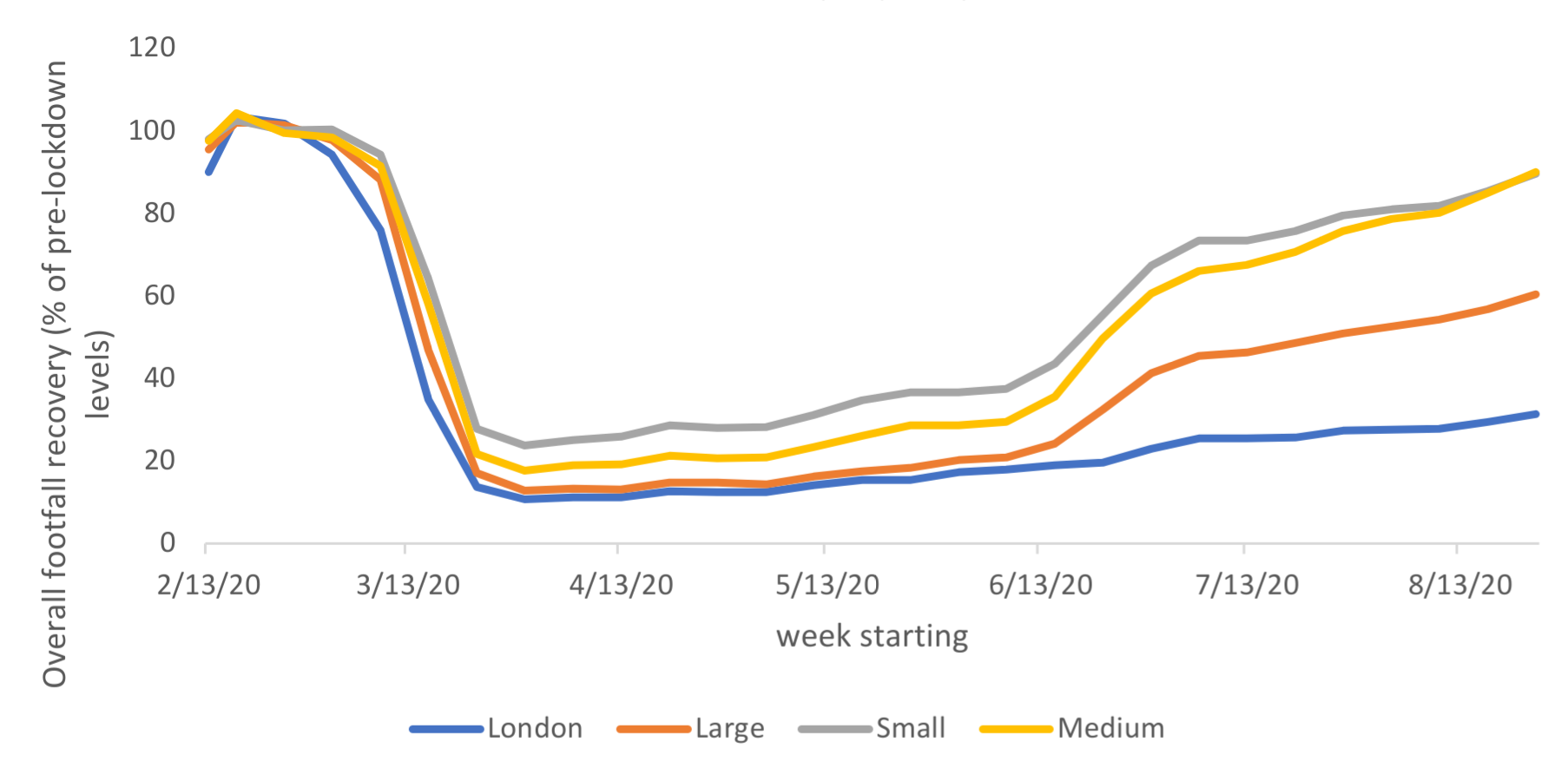

Larger cities, and London in particular, have struggled to recover

All city centres experienced a significant drop in footfall when the first lockdown started, but activity fell much further in larger cities. Partly as a result, when shops and pubs reopened earlier in the summer, small and medium-sized cities bounced back much quicker than London and other large cities. At the end of August, before the second wave hit, smaller cities had reached 90 per cent recovery, while in London it was only 30.

Figure 1: Footfall recovery by city size

Source: Locomizer, 2020

The reason why the reopening of amenities did not trigger massive flows of people back to the high street in larger city centres mostly has to do with work-from-home patterns. Because of the sectorial or industrial specialisation of their labour markets, different cities have a different proportion of their working population whose job can be done from home, and larger city centres tend to have a denser concentration of office jobs. In the UK, this varies quite significantly. In Barnsley, estimates suggest that only 18 per cent of workers can work from home, against more than 40 per cent in London.

This has had a massive impact on retail and hospitality

To some extent, the pre-pandemic strength of large city centres, which saw daily inflows of workers who poured money into the local economy by getting a sandwich for lunch or staying in the evening for dinner, has become a weakness. This has a knock-on impact on the high street businesses which lost their customer base, whether in the hospitality or retail sector. In London, for instance, the latest update of the High Streets recovery tracker showed that only 30 per cent of people were back – meaning 70 per cent fewer customers for these sectors, and putting almost half a million jobs at risk.

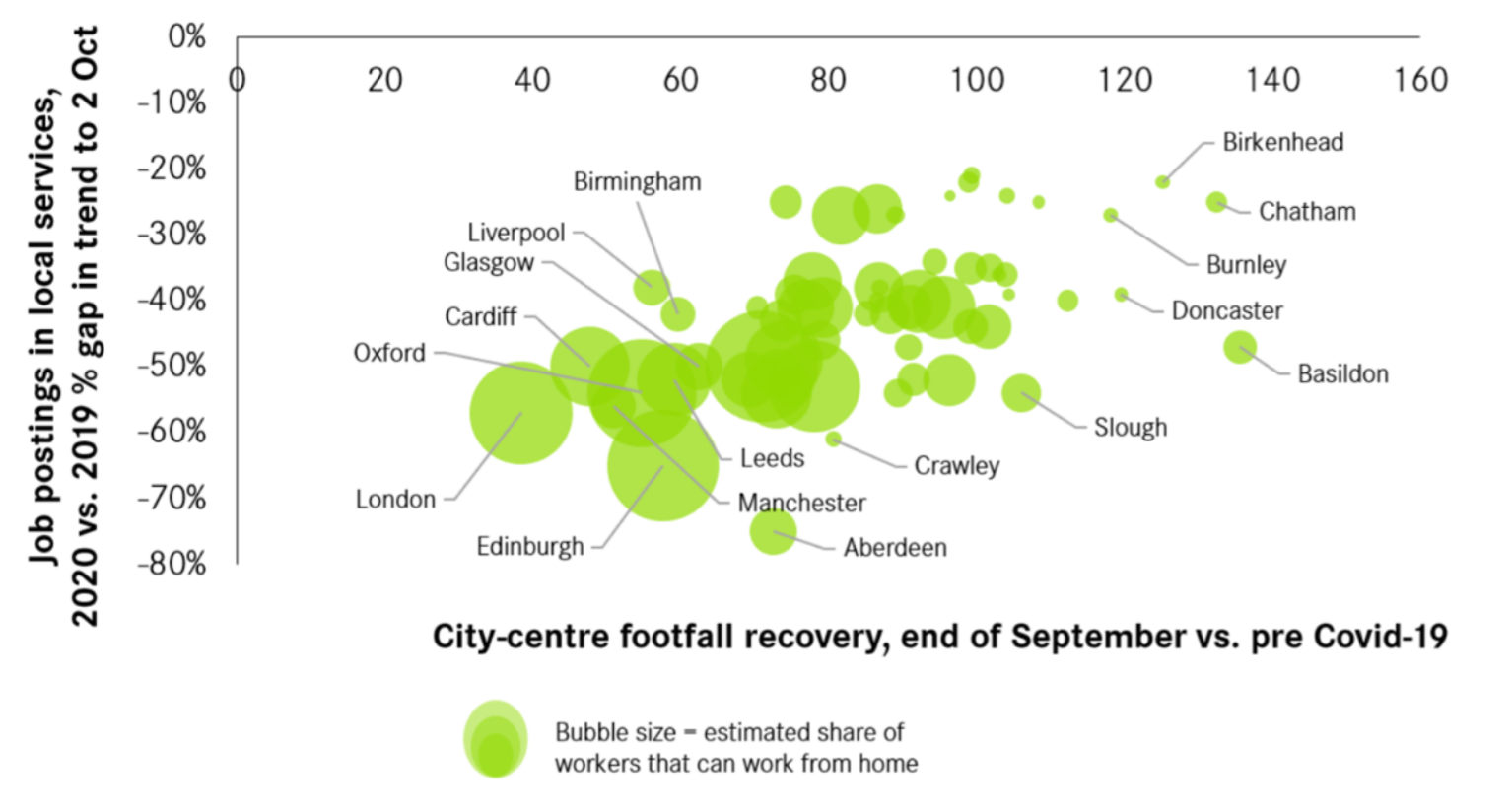

Looking at the relationship between the bounce back in footfall and the recovery in job postings for local services, we can see that the latter are slower to recover where more people work from home and stay away from city centres.

Figure 2: Job postings, work-from-home estimates and city centre footfall estimates, to end September 2020

Source: Indeed, Locomizer and Centre for Cities’ own calculations

This brings us to an interesting point about the impact of this crisis on inequalities. Does it mean that we’re now witnessing a levelling of the economy? Have inter-urban inequalities narrowed because it was (in September) easier to find a job as a bartender in Doncaster and Burnley than in London and Oxford?

Not really, because this is a relative recovery: the starting position in some places was already precarious. Take Doncaster, for instance, in the top right of the chart. Before the crisis Doncaster city centre was over-reliant on retail, which is now increasingly threatened by the rise of online shopping, and 18 per cent of its high street premises were empty. This was in marked contrast to a place like Oxford, which had already made the shift from retail towards more food and drink amenities, and only had an 8 per cent vacancy rate.

What this means is that the city centres which have seemingly suffered the least from this crisis actually face the toughest long-term challenges. In large cities like London, Manchester and Birmingham, a recovery will require workers to return, and if they don’t, more jobs will be lost. But it will only take workers to come back for these city centres to become vibrant again. In Birkenhead and Burnley, pre-COVID challenges will still need to be addressed by a range of policies, such as investing in skills.

In the past nine months, high streets have faced successive local and national lockdowns. Restrictions in the Christmas period, usually the busiest of the year, are likely to have compounded this. High streets are no doubt entering 2021 on their knees. But cities will bounce back – it’s a matter of when, not if – so let’s hope the vaccine rollout accelerates that. As the UK again goes into lockdown, Centre for Cities will continue to monitor the health of high streets and how it plays out across the country, so watch this space.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.