Both the Conservatives and Labour are keen on a ‘Covid bond’, which would encourage savers to fund the post-pandemic recovery. But the economic rationale is not immediately clear. Natacha Postel-Vinay (LSE) looks at how bonds could help the government navigate two possible challenges: rising inflation and tax hikes.

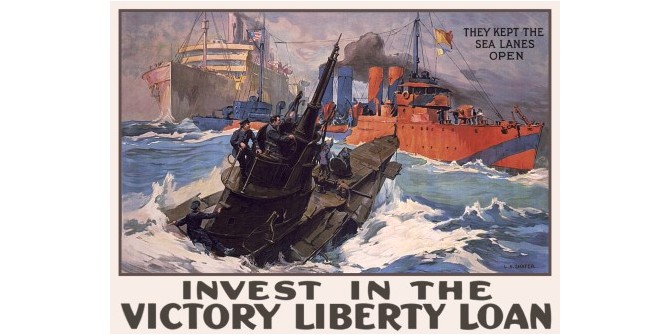

During the second world war, the UK government needed money badly, but it couldn’t raise taxes: people were already sacrificing a great deal for the war effort, and increasing taxes would have been very unpopular. At the time international markets were less developed and interest rates high, making it was more difficult to borrow through that route. So war bonds were issued. They were not a new idea: in 2014, the Treasury announced it would repay the 5% bonds sold a century before, though efforts to recruit savers during the first world war had not been particularly successful. But in 1940 the government launched a big advertising campaign urging people to ‘Save Your Way to Victory’ by patriotically investing in Britain’s future: ‘War Bonds Are Warships.’ The US (‘Liberty Loans’), Canada and other European countries also issued them.

Now both some Conservatives and Labour have expressed an interest in ‘Covid bonds’ – or, as Keir Starmer described them in his speech on 18 February, ‘British recovery bonds‘, whose proceeds would go to a new National Infrastructure Bank. In some ways, this is surprising. Interest rates are very low, so governments can borrow cheaply. It is not clear that international and institutional investors would find ‘Covid bonds’ more attractive than other forms of UK government debt. So the appeal will presumably be to ordinary citizens – perhaps older, wealthier people who have been unable to find much to spend their income on during the pandemic, and accumulated savings which are earning a poor rate of interest in banks and building societies. The Covid bond interest rate would offer a better rate than High Street banks currently do – perhaps 2% in five- or 10-year issues – and the bonds would be advertised as a patriotic investment to get Britain back on its feet.

However, that still doesn’t explain why issuing Covid bonds would be economically helpful for the government. But I can imagine two scenarios in which they might become useful.

The first is in the event that people go on a spending spree after the pandemic is over, pushing up inflation and therefore leading to a rise in interest rates. A mini-boom would be good for the economy, but too much demand creates scarcity and that will increase inflation. If the Bank of England does raise interest rates, government debt will end up being more expensive, and a 2% bond would encourage people to save rather than splurging their cash and driving up inflation further. Two per cent is more than it pays now, but less than it would have to pay if rates rise significantly.

Nonetheless, investors will ask themselves how secure Covid bonds are. In 1927 and 1932, for example, the government had to convert interest rates because it could no longer afford to pay back the promised amount.

Another reason why Covid bonds might appeal to the government is that they would be a way of securing public consent for the planned tax hikes. This quid pro quo would sweeten the pill of a tax rise. But the danger, as John Maynard Keynes and Winston Churchill argued in the 1920s when Austin Chamberlain increased taxes, is that this fiscal consolidation would be seen as redistributing wealth from taxpayers to ‘idle savers’. Much would depend on what kinds of taxes the Chancellor decides to raise, and on the bond buyer profile. In short, Covid bonds may be of limited practical appeal to the government right now, but as we emerge from the pandemic their use could become apparent. So would their challenges.

This post represents the views of the author and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE.

Hi,

Would there be a case of reintroducing the savings stamps of the 50’s and 60’s that were available from the Post Office at that time.??

Patriotic reasons might tempt savers of all ages (including children) to buy stamps as and when they felt like it with no reward payable but with a cast iron guarantee that the money was totally safe like the NS & I. The sole benefit to savers would be peace of mind in the knowledge that the savings would be risk free and stamps could be cashed in easily and without fuss. Children were able to buy stamps weekly from the teacher in the classroom in the 60’s.