The COVID-19 outbreak has proved to be a critical turning point for China, write Chris Alden and Kenddrick Chan (LSE). Facing increasing global criticism over claims that it intentionally misled the world by covering up the true extent of the coronavirus, China has now sought to actively push back against such criticism. Termed ‘Wolf Warrior’ diplomacy, this pushback has been noted for its propensity to call out and aggressively hit back against perceived criticism against China. Twitter is the platform where this new brand of Chinese diplomacy is most prominent. Data gleamed from the official Twitter accounts of various Chinese embassies and spokespersons reveal that official Chinese Twitter activity has gone into overdrive as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic, indicating China’s desire to influence and shape the debate via its new diplomatic strategy.

Why is China using Twitter for diplomacy?

Although virtually all of the 193 of the UN member states (including China) have some form of presence on Twitter, China is relatively new to using Twitter as a platform for diplomacy (“Twiplomacy”) with the official account of the Chinese Foreign Ministry (@MFA_China) having joined only as recently as 2018. Nonetheless, as the data will show, there has been a relative surge in the amount of Twitter activity of official Chinese accounts since the COVID-19 pandemic broke out. There are three possible intertwined reasons for China’s active embrace of Twitter as a platform to conduct public diplomacy, with all three reasons largely revolving in some way or other around the notion of public opinion management.

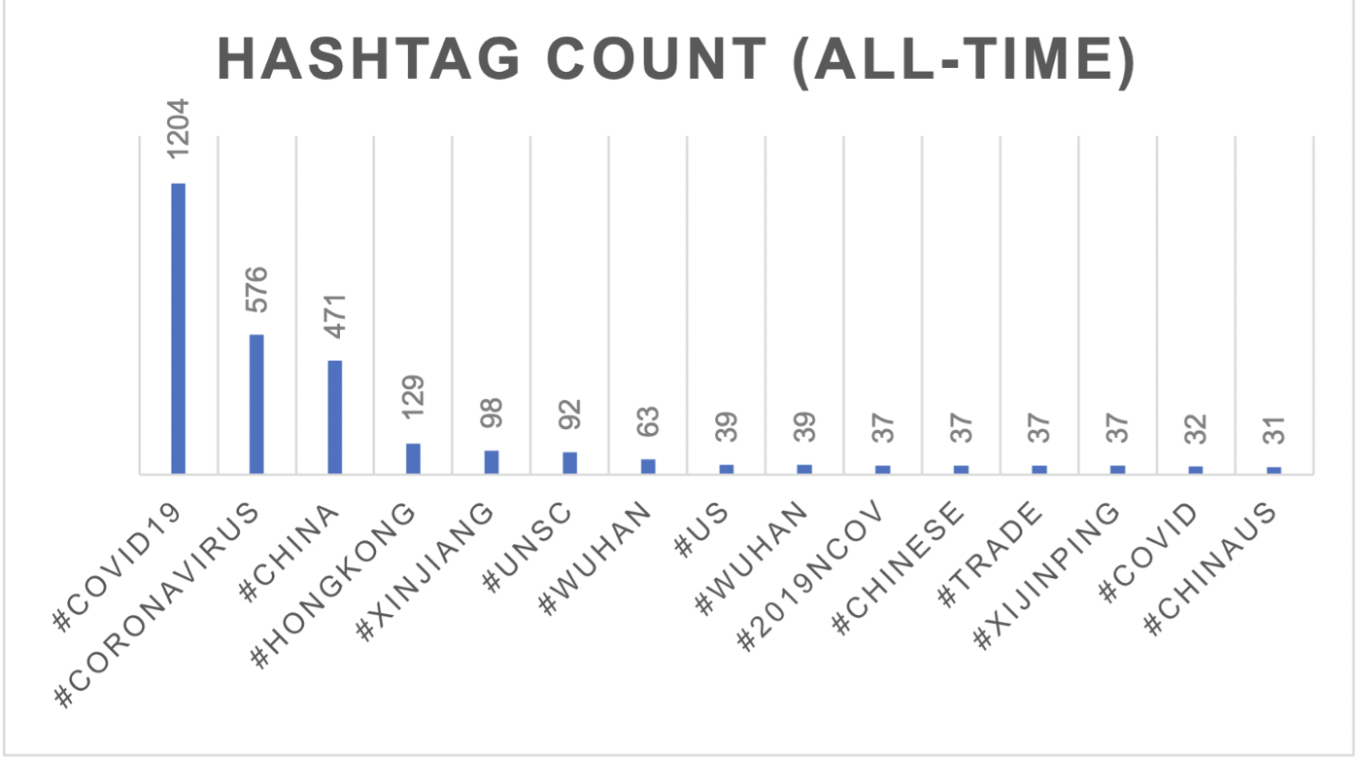

The first reason is the targeted outreach capabilities that Twitter has to offer. Twitter activity is often characterised by the presence and prevalence of the hashtag (#), which allows users to ‘tag’ their posts to a wider conversation. Twitter therefore enables China to reach an international audience (Twitter’s userbase) rapidly and effectively. By utilising the hashtag in the messages it puts out, China ensures that other Twitter users will be able to see the messages that its accounts put out when they search for the hashtag. This is regardless of whether these other users follow its accounts. Twitter also encourages brevity by limiting messages to only 280 characters, therefore affording China the necessity of skipping the pleasantries and getting ‘straight to the point’. For example, by using the #covid19 or #coronavirus hashtag in its tweets, China ensures that those tweets will show up in the search results of those looking to see the latest or top tweets on COVID-19. By using Twitter, China is therefore afforded the ability to select certain topics and put out its viewpoints in the hope of potentially swaying a wide international audience.

This leads us to the second reason, which is Twitter allows China to monitor and gauge international public opinion. As Twitter enables China to “broadcast” to the world, so too can it work the other way around. As evidenced by the Arab Spring or China’s censorship of its domestic social media landscape, Chinese policymakers are no strangers to the potentially intense digital public sentiment generated when it comes to heralding in large-scale social changes. Twitter therefore serves as a platform for Chinese diplomats to directly monitor and gauge the opinion of foreign publics towards it. Considering that traditional media sources have a much longer turnaround time as compared to social media platforms like Twitter, the insights that Twitter can provide as the situation changes ‘on-the-ground’ can be especially valuable at preformulating responses, especially when it comes to a rapidly evolving event such as the COVID-19 pandemic.

The third reason for China’s official usage of Twitter is the possibility that key members within China’s inner policymaking circle are now privy to the impact the platform can offer when it comes to public diplomacy and pushing back against what China views as unwarranted criticism. In one famous example, Zhao Lijian, the former Chinese deputy chief-of-mission (DCM) to Pakistan, deflected criticism of Chinese internments camps in Xinjiang by making statements concerning the racial composition of neighbourhoods within the United States. This provoked a heated public exchange on Twitter with the former US National Security Advisor Susan Rice. With close to 700,000 followers on Twitter — more than any other official Chinese Twitter account, Zhao now serves as the official spokesperson of the Chinese MFA, an indication that his higher-ups in Beijing are aware of the impact Twitter as a platform can have on its international messaging efforts.

How does China’s MFA use Twitter diplomacy?

To get a better idea of how China uses Twitter, we first looked at several official Twitter accounts of Chinese foreign policy entities (embassies and aid agencies). By connecting to Twitter’s API, we were able to access and extract the latest 3200 tweets (the maximum allowed) sent out by each of the following accounts. (Note that the extraction limit of 3200 tweets for each account is more than sufficient, considering that none of the accounts have even hit the 3200 tweet count.)

Chinese Ministry of Foreign Affairs @MFA_China

Chinese Mission to UN @Chinamission2un

Chinese Embassy in US @ChineseEmbinUS

Chinese Embassy in South Africa @ChinaAmbSA

China Int’l Development Cooperation Agency CIDCA @cidcaofficial

Apart from the tweets, other related data such as hashtag count, post type (tweet/retweet/reply) and user mentions were also extracted. All the data was then compiled and analysed accordingly. The following are our findings:

Finding 1: Twitter is used to discuss controversial issues, especially COVID-19

Looking at the combined all-time hashtag count of Chinese Twitter activity, we found that issues where China uses hashtags tend to be controversial issues. As stated earlier, the use of hashtags possibly indicates a desire by China to influence the conversation. A look at the top hashtags used by China (visualised in the chart below) show that COVID-19 leads the pack, followed by other controversial issues such as Hong Kong and Xinjiang, with other issues being relatively insignificant.

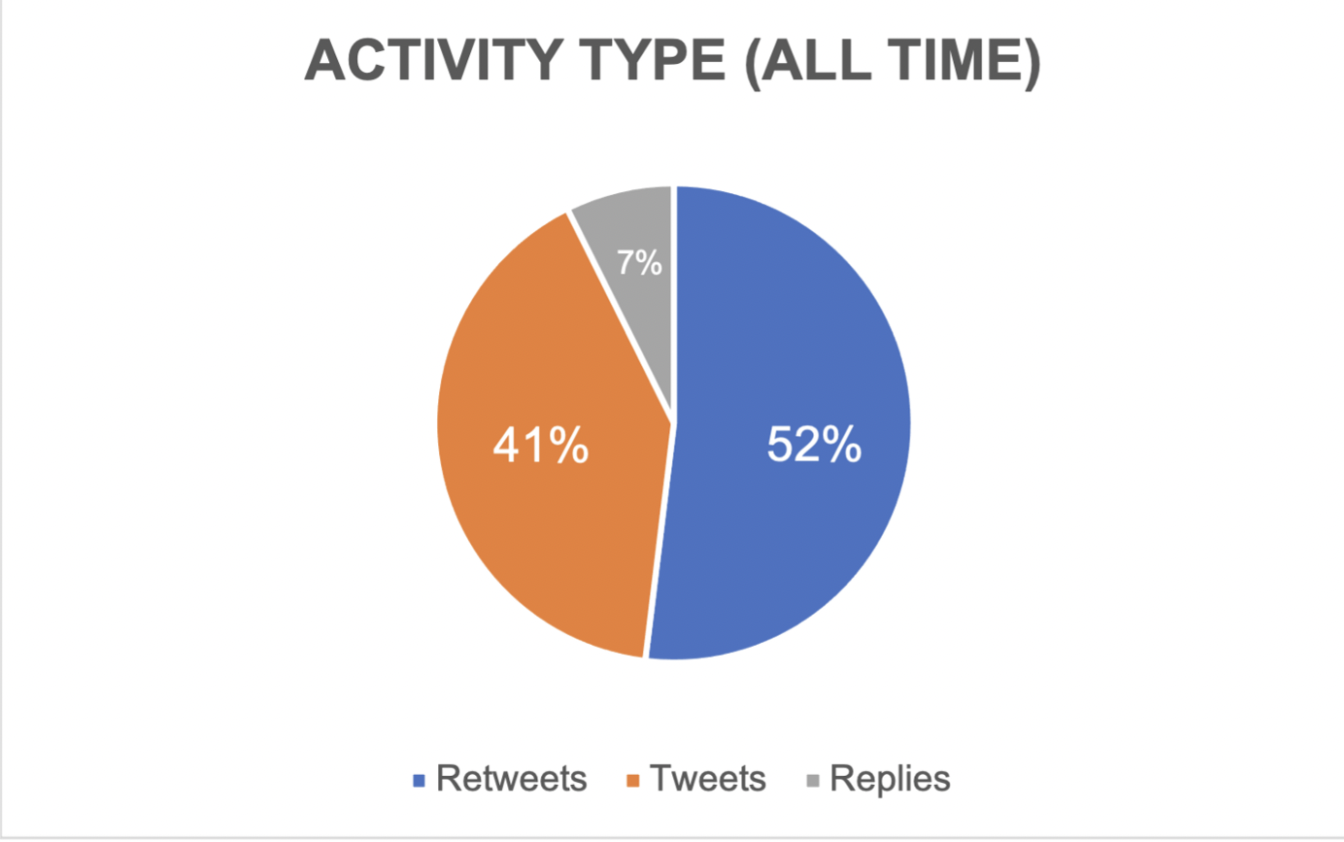

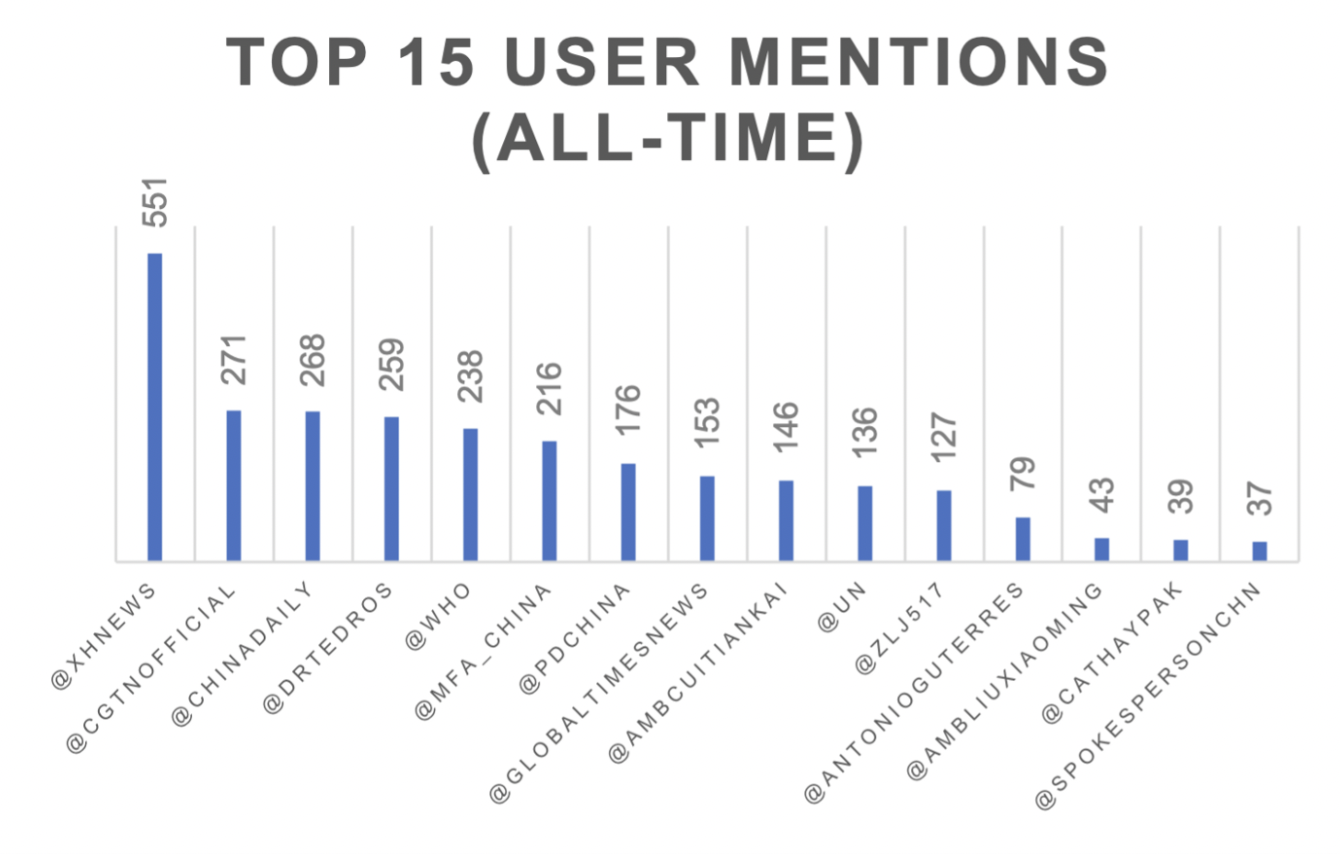

Finding 2: China’s narrative on Twitter remains tightly controlled and curated

Looking at the type of tweets, it appears that most official Chinese embassy accounts have a weak preference for retweeting (52%) rather than tweeting (41%). Direct engagement in dialogue appears to be rare (7%). As for the sources of retweeting, it appears that these official PRC embassy accounts having a primary preference for retweeting from state-based news media agencies. A look at the top 15 retweet sources shows that media outlets Xinhua News Agency, China Global Television Network (CGTN), China Daily round up the top three, with People’s Daily and Global Times coming in at 7th and 8th place respectively.

Interestingly, the preference for retweeting from official state media sources (which are vetted prior to official publication) as opposed to actual ambassadors seem to suggest the importance of retaining the ‘core message’ or narrative. As seen with Zhao Lijian’s verbal confrontation with Susan Rice, ambassadors might veer too far ‘off-track’ from expected standards of personnel conduct and diverge too much from the CCP party line — possibly explaining why tweets from ambassadors are lower in precedence as compared to state media sources. Other non-“wolf warrior” diplomats of the Chinese MFA had previously emphasised the need to steer clear of ‘extreme’ views if possible. Unsurprisingly, when asked about Zhao Lijian’s verbal confrontation with Susan Rice, the spokesman of the Chinese MFA indicated that the organisation was not aware of the specifics of the situation.

Performing time series analysis on the tweets to detect keywords spikes (which are associated with significant events) shows that COVID-19 related keywords only occur on 28 January, almost a full week after the lockdown was initiated in Wuhan and just two days before the World Health Organization declared a public health emergency. This strongly indicates that China views its use of Twitter as an extension of its desires to shape the global debate on China and COVID-19. This remained pertinent in the months following the onset of the pandemic, considering that the Chinese Ministry of State Security has warned Chinese leaders that China faces the highest levels of global anti-China sentiment since the 1989 Tiananmen Square incident. Similarly, performing sentiment analysis (using the SentiStrength opinion mining algorithm) on tweets since 30 December 2019 (when China went public with COVID-19) shows the language of China’s Twitter diplomacy to be carefully curated to avoid any perception of over exaggeration. For example, positive sentiment tended to be moderately-positive (91.85%) with the main words associated with the positive sentiment being: great, congratulations, good, hope, respect, progress etc.

What does this mean for Chinese Twitter diplomacy in the future?

Our reading of China’s Twitter diplomacy suggests that there are already some clear trends and even speculative avenues for understanding how China might use Twitter for diplomacy in the near future. First, the usage of Twitter diplomacy is effectively a ‘crisis messaging tool’ for Beijing. The global nature of the issue and its immediate strategic importance to China defines the necessity of utilising the Twitter to shape the emerging debate on a given topic, given how Twitter is the “preferred channel” for conducting digital diplomacy. Due to widespread domestic and international criticism of its handling of the COVID-19 pandemic, China’s carefully crafted image of itself as a capable global leader was in danger of receding.

Faced with momentous pressure to push back against an anti-CCP narrative, the Chinese authorities have sought to use Twitter as a vital instrument in their efforts to do so. Twitter provided an instrument for swift, targeted rebuttals that reached a global audience in near real-time. Twitter has served as a platform through which China can push out swift and targeted rebuttals, all whilst reaching a global audience. Twitter diplomacy has therefore given China some much-needed breathing room.

We note that as the COVID-19 crisis has ‘normalised’ in recent months — arguably a mark of China’s relatively successful transition out of crisis — and the focus has shifted to other countries’ management of the crisis, this has allowed other issues is creep up the agenda. As a result, Beijing’s use of Twitter diplomacy has similarly become routine, and the accompanying volume of traffic related to the COVID-19 pandemic has decreased in comparison from the height of the outbreak. We anticipate that this trend will continue, with China’s Twitter activism surging in line with its perceived necessity of managing the crisis narrative of a given issue. Doing so will allow Chinese authorities to potentially pre-empt any unfavourable narratives from gaining momentum.

Secondly, despite MFA’s granting of a measure of autonomy to ambassadors to communicate with the foreign public, the logic of the top-down party hierarchy, in many ways reflective of Xi Jinping’s centralisation of power, seems to have prevailed. Ambassadors who have developed distinctive voices over the last 20 or so months by entering into the national dialogue of their resident countries via Twitter are becoming less evident. The most vocal of the “wolf-warriors”, Zhao Lijian and Lin Songtian, have been recalled back to lead various key departments of China’s foreign diplomacy apparatus. For example, Lin Songtian is now the president of the Chinese People’s Association for Friendship with Foreign Countries (CPAFFC), an organisation known as the “public face” of the Communist Party’s United Work Front Department.

This indicates a conscious decision on the part of the party leadership to reign in such ambassadors while still retaining the benefits that “wolf-warrior” diplomacy provides. Additionally, what is notably absent to date in the Chinese approach to Twitter diplomacy is the kind of individual messaging pursued by national leaders, most notably with Trump but also many others. India’s Narendra Modi, Turkey’s Recep Tayyip Erdogan and Malaysia’s Mahathir Mohamad are good examples. It seems certain that a modern-day Mao Zedong, well-published in his day and whose legacy is undebated amongst Communist Party members, would have taken to social media with much ardour and alacrity.

Finally, in an era of global power competition and the growing trend towards a ‘splinternet’ in the digital world, how will this affect China’s Twitter diplomacy? Will the regulatory regimes currently being discussed and possibly implemented by the West’s social media giants impact China’s use of this platform? If so, how? Irrespective, it is hard to imagine that Beijing, having recognised the power of Twitter diplomacy in shaping global public opinion towards China on COVID-19, will not find a means of engaging audiences on social media to convey its messages in the future.

This post represents the views of the authors and not those of the COVID-19 blog, nor LSE. It first appeared at the LSE Ideas blog. The PDF of this article can be found in the list of Strategic Updates by LSE IDEAS and can be accessed here.