The Polish economy has largely managed to avoid the pandemic-induced troubles experienced in Western Europe. But as Paweł Bukowski (LSE) and Wojtek Paczos (Cardiff University) argue, contrary to government claims of able stewardship, what has got the country through relatively unscathed is a combination of good fortune, making GDP a priority over health and restrictions centred more on personal freedoms than economic freedoms.

In 2020, Poland’s GDP contracted by ‘only’ 3.5%, significantly less than the OECD average of 5.5%. In the UK, the comparable figure stood at a staggering 9.9%. While unemployment rates have soared across Europe, the official Polish figures have hardly budged, and are the lowest in the European Union, according to Eurostat figures in early 2021.

We should keep in mind that the Polish economy was also performing very well before the pandemic. It had been forecast to grow by 3.1% in 2020, according to the International Monetary Fund’s (IMF) World Economic Outlook from October 2019. But the Polish economy’s drop to 6.6 percentage points below the expected growth figure is still a milder slowdown than in many other countries. For example, in the case of the Czech Republic, it was 8.1 percentage points (from +2.6% to -5.5%), Hungary 8.3 percentage points (from +3.3% to -5%), the UK 11.4 percentage points (from +1.4% to -10%) and Spain almost 13 percentage points (from +1.8% to -11%).

While the Polish economy has clearly managed to navigate the pandemic relatively well thus far, the reasons for this are less clear. The country’s government has been quick to claim the success of its various anti-crisis measures. The reality, however, is that the Polish response to the economic fallout was neither more innovative nor more generous than those of other countries. According to Eurostat, public spending rose by 9.1% of GDP in Poland between the first and third quarters of 2020, while the EU average in that period was 10.1%. Contrary to government claims, we think that a relatively lax approach to economic lockdown and a bit of sheer luck are the main reasons for the relatively good performance of the Polish economy.

Getting lucky in the first wave

By ‘sheer luck’ we mean all the factors that are beyond the direct control of policies but affect the transmission of the pandemic and the country’s economic fortunes nevertheless. Poland was ‘lucky’ in three important respects: its semi-peripheral location and its geographical as well as economic structures. As we will argue, those factors markedly affect the trade-off between the economy and public health.

Due to its semi-peripheral location, the first coronavirus case appeared in Poland relatively late, giving the government more time to prepare and implement a lockdown strategy. The first restrictions were introduced when the seven-day average of daily cases stood at just nine – rather than 674, as was the case in the UK. New research by the IMF suggests that early but tight lockdowns are most effective in containing the spread of the virus. They are also (potentially) the least harmful to the economy because, if successful, they can be lifted more quickly.

Second, Poland’s geographical structure meant that the ‘natural’ speed of transmission in Poland was slower than in more densely populated West European countries. In Poland, 40% of the population lives in the countryside, which greatly limits the number of daily contacts. The ‘lived density’ of the population in Poland equals only 196 per populated square kilometre, compared with 531 in the UK.

Restrictions: when, what and how?

During the first, spring 2020 wave of the coronavirus, there was no statistically significant increase in the number of excess deaths (above the five-year average) in Poland and the economy was doing well. The policy of early and tight restrictions circumvented the painful trade-off between public health and the economy. This changed dramatically during the second, autumn wave of the pandemic, which reached its peak in November. The government then implemented a ‘wait-and-see’ approach, introducing belated measures that ultimately proved less adequate. This can be interpreted as favouring the economy over public health.

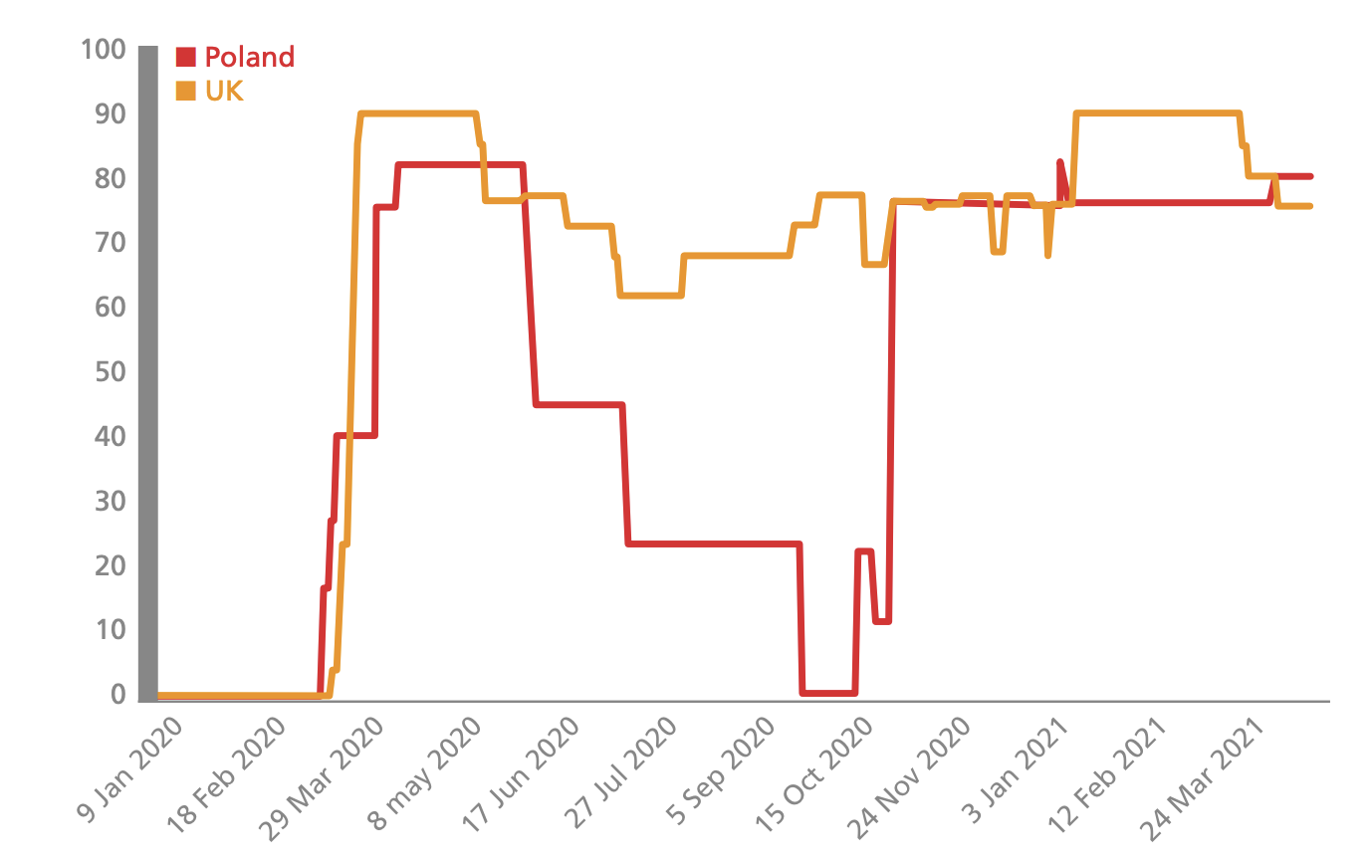

In Figure 1, we modify the Oxford Covid-19 stringency index to show the composite measures that are most harmful to the economy. The original index is based on nine indicators rescaled to a value from 0 to 100, where 0 is the pre-pandemic situation and 100 stands for the most stringent measures implemented in all categories. Our modification includes six categories that we believe are most harmful to the immediate economic situation. We exclude school closures and bans on international travel and include the remaining six categories: workplace closures, cancellation of public events, restrictions on gatherings, limits on public transport, stay-at-home orders and internal movement restrictions.

The economic severity index

Figure 1 shows that the Polish restrictions were strict during the first wave and then almost nonexistent in the summer. The increase in restrictions in the autumn, when compared against the number of cases, is, in our opinion, much belated. By contrast, in the UK the restrictions were kept high during the summer and the increases in restrictions in the autumn were much better timed. This may have hurt the economy more, but also resulted in the much slower transmission during that second, autumn wave. The difference, in some part, may also be explained by a different approach to restricting economic and personal freedoms in each country.

Our intuition is that the Polish approach put less burden on the economy, while the British one is probably more effective in limiting virus transmission

In the UK, for example, there have been few limits on individuals: masks were never made compulsory outdoors; schools remained open for several months; and – from the authors’ own experience – quarantine enforcement has been relatively lax. But home-working was recommended for almost the entire year. During the lockdowns, Britons could only buy nonessential products online and had no access to any form of indoor services.

Figure 1: The economic severity index in Poland and the UK

By contrast, in Poland masks were made compulsory even on empty streets, schools were fully opened for only six weeks, and those in quarantine were checked on regularly by police officers. But remote work was only strongly pushed for a few scattered weeks. For most of the past year, Poles could still go to a shopping mall or even visit a sauna. Our intuition is that the Polish approach put less burden on the economy, while the British one is probably more effective in limiting virus transmission.

This is supported by the data relating to the total death toll of the pandemic. We use a measure of ‘excess mortality’ (number of deaths above the five-year average) as these data are free from potential differences in (mis)reporting and classification. During the first wave in spring 2020, early and tight lockdown in Poland resulted in virtually no excess deaths, while in the UK delayed restrictions led to excess mortality of over 100%. But then the situation was almost the reverse during the second, autumn wave. In the year between March 2020 and March 2021, the UK lost almost 121,000 additional lives, while Poland lost more than 95,400. In relation to the country’s respective populations – with the UK being 80% more populous – Poland had 42% higher excess mortality per capita. Virtually all of the difference falls on the second wave.

Services suffer, manufacturing booms

Moreover, the composition of the Polish economy also makes it more resilient to lockdown measures. In 2019, 27% of workers were employed in sectors that were later directly affected by the lockdown (such as hospitality or tourism), compared with 34% in the UK and 37% in Spain, according to Eurostat. Since a smaller part of the economy had to hibernate, the direct effect on GDP was less negative. But there was also a second, indirect, channel. Poland is the only big EU country that has a growing share of manufacturing in both employment and production. This kept more of the economy humming when the services sector had to be locked down. Also, thanks to this, the country was able to benefit from the global shift in consumption from services to durable goods induced by the pandemic.

Size matters too. A big domestic market reinforces the positive effects of the business-friendly lockdown and a resilient economic make-up. Smaller countries in the region, such as Hungary or Slovakia, are more dependent on the economic situation in the rest of Europe. The larger economic fallout in Germany or the UK will thus drag down smaller economies more.

Because of its size, Poland’s domestic economy could in part compensate for the loss of external demand. Poland and the UK pursued different paths during the first and second waves of COVID, providing a natural experiment on how the form and timing of lockdown policies can affect economic slowdown and virus containment. Moreover, the sectoral composition of the economy and geographical distribution of the population also play crucial roles. Although the performance of the Polish economy during the pandemic appears surprisingly robust, we do not think it was the result of a thought-through strategy. On the contrary, percentage points in GDP figures can never justify the price of almost 100,000 excess deaths. As the first wave in Poland demonstrated, this is a price that was entirely avoidable.

The original version of this article was published on the Notes from Poland blog in April 2021 and subsequently on LSE EUROPP and in the Centre for Economic Performance’s newsletter.