France votes on Sunday in the second round of elections for the lower house of its parliament, the Assemblée nationale. New President François Hollande has been lauded for appointing a parity government, but what are the chances of equality in parliament after the coming elections? Using data from the presidential and the first round of the parliamentary elections Rainbow Murray predicts a rise in the number of women députées from the current 19% to nearly 30%. While this is a significant improvement, parity is still clearly a long way off.

France votes on Sunday in the second round of elections for the lower house of its parliament, the Assemblée nationale. New President François Hollande has been lauded for appointing a parity government, but what are the chances of equality in parliament after the coming elections? Using data from the presidential and the first round of the parliamentary elections Rainbow Murray predicts a rise in the number of women députées from the current 19% to nearly 30%. While this is a significant improvement, parity is still clearly a long way off.

In May, François Hollande appointed France’s first parity government (albeit with women mostly in less powerful roles). Will this achievement be mirrored by a similar proportion of women in parliament, some twelve years after France passed a gender parity law?

When this law was enacted in 2000, women’s level of representation in parliament had barely broken into double figures and France lingered near the bottom of international league tables. It was in this context that France became the first country in the world to introduce a 50% gender quota. If the law was ambitious, its outcomes thus far have been modest; the proportion of women crept up barely a single point to 12.3% in 2002, then rising to 18.5% in 2007. Reasons for these disappointing outcomes include France’s electoral system, with single-member districts placing a heavy emphasis on incumbents who are predominantly male and difficult to replace. The law also applies only to candidates and not to the number of women elected, leading parties to field women predominantly in unwinnable seats. Finally, the sanctions for non-implementation are a reduction in state subsidy that mainly constrains small parties, while large parties opt to lose millions of Euros each year rather than select more women candidates. Parties on the right have been particularly slow to feminise.

Why expect an improvement after the 2012 parliamentary elections? Firstly, the financial penalties for non-implementation have increased by 50%, making it even more costly for parties to circumvent the law, although this does not address the ongoing issue of women’s placement in unwinnable seats. An additional cause for optimism is the anticipated return of the left to power for the first time since the law was enacted. Left-wing parties have consistently performed better for women’s representation (indeed, the proportion of women elected would have been substantially higher in 2002 and 2007 if the left had won). Furthermore, having been out of power for a decade, they have a number of target seats with neither a male incumbent, nor a previous occupant of the seat seeking to reclaim it. This has enabled them to select women in potentially winnable seats. Hollande’s Socialist Party claimed that up to 40% of their seats would be held by women after the election. Does this claim hold up, and what will the rest of parliament look like?

I ran two different models to forecast the gender composition of the French parliament after the election. The first uses second round data from the presidential election. Within each parliamentary constituency, if Nicolas Sarkozy won more than 50% of the vote, I assume that the leading candidate on the right would win the seat, and vice versa for left-wing candidates where Hollande led. While the presidential elections are a good predictor of the overall outcome of parliamentary elections, this model is somewhat crude as it takes no consideration of other constituency factors, such as incumbency effects. Dissident candidates may qualify at the expense of the official party nominee, and the presence of a far-right candidate in the second round might split the vote and alter the predicted outcome. Despite these caveats, this model is still a useful indicator of whether women are being placed within seats that their party might aspire to win, and it compensates for the forecasting limitations presented by recent redistricting.

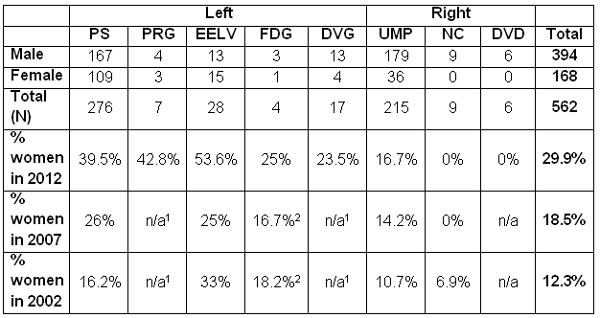

Table One: Forecast of women MPs using results of presidential election

1 Data for the PRG and DVG are incorporated into the data for the PS in 2002 and 2007

2 Figures for 2002 and 2007 are for the Parti Communiste Français

Table One provides an overall estimate of nearly 30% women elected, which is a dramatic rise on previous years. This reflects an improvement across most parties, but especially those on the left. According to this model, the Socialists have indeed honoured their promise of electing 40% women. However, the poor performance of parties on the right has pulled down the overall proportion of women.

The second model uses the first round results of the parliamentary elections. Some seats were won in the first round (if a candidate obtained an absolute majority of votes). Similarly, in some seats only men or only women have qualified to the second round. For all these seats we can already be certain of the sex of the deputy. In some other “safe” seats, the sex of the likely victor can be predicted fairly reliably. In the remaining seats, the result is too close to call because the seat is very marginal, has a high proportion of far-right voters whose second round voters are uncertain, or is otherwise unstable. Where these seats featured at least one candidate of each sex, with no clear picture of who would win, the sex of the victor could not be forecast.

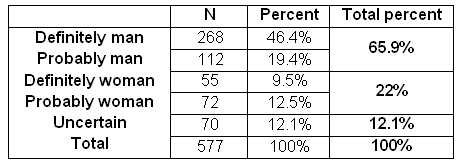

Table Two: Forecast of women MPs using first round parliamentary election results

This model provides a much more modest forecast for women. There are few seats where a woman deputy is guaranteed. Of the 500 seats where the result could be estimated, women won only 127 seats (25.4%). If we assume that women have an equal chance of emerging victorious in one of the uncertain districts, this would rise to 162 seats, or 28%. This is more in keeping with the first forecast, although the lower estimate and greater uncertainty both reflect the fact that women are more frequently placed in marginal seats. This builds on findings in my earlier research indicating that women are more often found in seats that are harder to win and easier to lose. The proportion of female Union for a Popular Movement (UMP) deputies would have been even lower in 2002 were it not for the scale of the UMP’s victory, resulting in women winning seats that would normally go to the left. If these seats now return to the left, the benefits of a left-wing victory will partially be offset by the electoral wipeout of many women on the right.

It appears that the French may still be some way from the elusive goal of parity, despite increased efforts from all sides. Nonetheless, it is clear that 2012 will see a sharp rise in French women MPs. For the first time, France will overtake the UK, possibly by a considerable margin. If the French can overcome the many hurdles to women’s representation, why can’t the UK do the same? Time for a British gender quota à la française?

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/KsJPpa

_______________________________________

Rainbow Murray – Queen Mary, University of London

Rainbow Murray – Queen Mary, University of London

Rainbow Murray is a Reader in Politics at Queen Mary, University of London, and a visiting research fellow at CEVIPOF (Sciences Po, Paris). Her research interests lie in political representation, gender and politics, candidate selection, French and comparative politics, political parties and elections. She is the author of Parties, Gender Quotas and Candidate Selection in France (Palgrave, 2010) and the editor of Cracking the Highest Glass Ceiling: A Global Comparison of Women’s Campaigns for Executive Office (Praeger, 2010).