One of the key challenges European policy-makers face in the context of the Eurozone crisis is tackling rising unemployment rates. Katrin Suder, Holger Haenecke and Julian Kirchherr argue that strengthening startups is one potential avenue to revive an economy. Drawing on the results of a case study on Berlin’s ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’, they outline a range of initiatives which can help jumpstart and accelerate the startup lifecycle in a city.

One of the key challenges European policy-makers face in the context of the Eurozone crisis is tackling rising unemployment rates. Katrin Suder, Holger Haenecke and Julian Kirchherr argue that strengthening startups is one potential avenue to revive an economy. Drawing on the results of a case study on Berlin’s ‘entrepreneurial ecosystem’, they outline a range of initiatives which can help jumpstart and accelerate the startup lifecycle in a city.

Europe’s labour market crisis is more alarming than ever: In the past twelve months Cyprus’ unemployment rate skyrocketed from 12 per cent to 17 per cent. In Spain, one out of every four people is unemployed. In Greece, every third adult is now out of work. Europe urgently needs more jobs, the big question is what policy-makers can do to boost job creation.

Strengthening startups may be one avenue to create more jobs. Indeed, policy-makers all over the world increasingly pursue this path. For instance, Berlin currently aims to launch a startup initiative to create more than 100,000 new jobs until 2020. London already started its entrepreneurial action plan in 2011 claiming to have raised its tech startups from 200 to 1,200 from 2010 to today. Meanwhile, Tel Aviv is running its “Startup City Tel Aviv” programme, which aims to create an “unparalleled early stage innovative ecosystem” in Europe and beyond. Many additional examples could be listed.

These examples raise a number of issues. Do they deliver on their promises? What can policy-makers really do to create or strengthen startup ecosystems that generate jobs and economic growth? What constitutes an entrepreneurial hub? To answer these questions, a team of 15 analysts conducted an in-depth case study on Berlin’s startup ecosystem which included more than 100 structured interviews with entrepreneurs, venture capitalists, corporations, policy-makers and academics from all around the world. In addition, about 500 reports, scientific papers and newspaper articles on the topic at hand were reviewed.

This new study constitutes a follow-up to “Berlin 2020- Fostering Competitiveness and Innovation“, our 2010 report on Berlin, which outlined strategic approaches to regional development for Germany’s capital. Many of the central findings of our new study can be extrapolated from Berlin to any emerging or current startup hub in the world. Our central findings are that entrepreneurs typically require capital, infrastructure, talent, networks and a city with a great entrepreneurial reputation and atmosphere to flourish. Indeed, a city’s reputation as a startup hub is largely the result of its capital, infrastructure and talent availability as well as its network density; a city’s overall atmosphere (cultural activities, bars and restaurants, architecture) –particularly evidenced by the case of Berlin – also plays a decisive role, though.

If policy-makers manage to address these 5 critical success factors (just as Berlin is trying to do now), a vibrant startup ecosystem can be constructed in many instances. The ideal tool to manage and coordinate the construction process is a delivery unit managing and coordinating implementation plans – in combination with a variety of particularly ambitious goals (‘stretch goals’) and concrete targets. Berlin is among the world’s top 15 startup hubs. Below we explain which questions cities need to ask in order to rapidly assess their performance as a startup hub. We also describe and provide examples for possible initiatives that could be undertaken to improve the startup outlook.

Capital

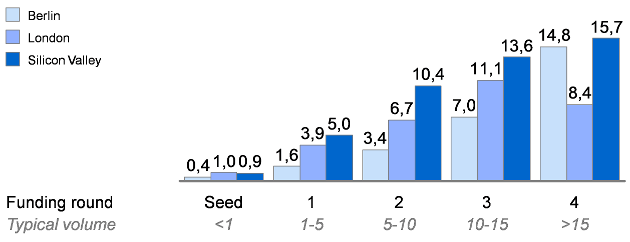

The first factor affecting a city’s startup ecosystem is capital. How easily can startups access financing along all stages of a company? How many of a city’s leading startups are funded by public funding instruments? Answering these questions helps assess a city’s availability of capital. One example of such an assessment is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1: Average deal investments in selected cities (millions of euros, 2000-2013)

Note: During ‘funding rounds’ start-ups raise capital from business angels and venture capitalists in order to scale their business. Typically, each successive funding round requires more and more capital. The ‘typical volume’ of a funding round depends not only on the development stage of the start-up and the validity of its business model, but also on its location, for instance. The data depicted above is based upon S&P registered transactions between 2000 and 2013YTD in the clusters digital tech, bio/med tech and urban tech.

Source: Capital IQ; McKinsey

Indeed, any entrepreneur needs capital to develop and scale its business. No startup life cycle will even begin if young companies lack cash. Policy-makers can strengthen both the availability of private and public capital. Additional private capital can be attracted if policy-makers actively reach out to leading venture capitalists. For instance, London’s Tech City Investment Organisation, the city’s official startup unit, formally engaged with more than 29 United States venture capitalists via calls, meetings and conferences in 2011/2012, which has significantly increased the city’s access to capital.

If overseas venture capitalists are hesitant to join a European startup ecosystem, public funding instruments may boost capital availability. Berlin’s venture capitalist fund “Technologie Berlin” is a prime example of such a public funding instrument. With a total fund volume of 52 million euros, and a ticket investment of up to 3 million euros, it supports leading startups from Berlin such as OctreoPharm, mysportgroup and madvertise. Successful public funding instruments manage to support as much as 30 per cent of a city’s top 25 startups.

However, public capital ought to particularly focus on companies’ seed phases; it is the policy-makers responsibility to initiate the startup life cycle, not to accompany young companies from their formation until the exit. Thus, engaging with overseas venture capitalists ought to be the preferred capital policy tool.

Infrastructure

What is the office vacancy rate in a city? What is the rent per square meter? Answering these questions helps to gauge a city’s infrastructure attractiveness. For instance, Berlin’s rents are comparatively affordable (starting from 4 EUR/m2 for industrial real estate), while its office vacancy rate is quite low (8.4 per cent). However, such initial analysis must be complemented by additional investigations. Startups also demand space that is located centrally and can be rented flexibly. Reliable and fast high speed Internet is also part of a city’s infrastructure, just as efficient transportation systems are.

The most successful startup hubs create the environments startups need to flourish. For instance, London convinced Google to launch its first Google Campus in the heart of East London’s Tech City. The corporation claims that it “has the hottest startups under one roof, who benefit from one-to-one mentoring and visiting speakers such as top entrepreneurs and business leaders“. Meanwhile, Singapore has set up more than 25 special offices for startups since 2009, allowing entrepreneurs to rent space for as little as 15 US dollars per day.

Talent

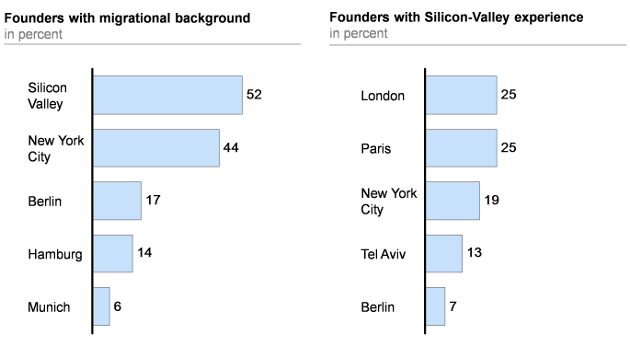

How many students start a business upon graduation? How many of a city’s entrepreneurs come from abroad? Answering these questions helps assess a city’s availability of talent – both domestic and foreign. Examples of such key talent metrics are shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Key talent metrics in selected cities

Source: Kauffmann Foundation; Bundesagentur für Arbeit; McKinsey

Indeed, a startup metropolis must be able to turn its brightest domestic minds into entrepreneurs rather than ‘corporationists’. In addition, it must be able to attract the most innovative and capable entrepreneurs from all over the world in order to truly boost its economy. Policy-makers can strengthen both the availability of domestic and foreign talent.

Nourishing entrepreneurial domestic talent starts at local universities. If professors advising student entrepreneurs are rewarded for their efforts, if there are a variety of courses in the curriculum related to startups, and if university competitions challenge students to found companies, then an entrepreneurial spirit is created in the medium-term which will eventually translate into more and better startups. The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is most likely the world’s prime example of the entrepreneurial university described here.

In terms of foreign talent, cities must be immigrant-friendly. However, attitudes of citizens towards migration are inherently difficult to influence. Policy-makers may create public one-stop-agencies answering all questions related to visas, working permits, driving licenses, the availability of office spaces and spots in the closest nursery for childcare. Nevertheless, locals sadly may still choose to send their children to a different nursery as a consequence of a large influx of foreigners in their district.

Language is one key enabler of successful migration. Cities whose operating language is English are at a natural advantage here. However, policy-makers can help to reduce language barriers in any city. For instance, Tel Aviv now runs almost all of its websites and publications in English, Arabic and Hebrew. Even most of its civil servants dealing with startups are now bilingual or even trilingual. Ideally, cities offer local language courses to new immigrants as soon as they have arrived.

Networks

How many events exclusively dedicated to startups (such as Berlin’s Startup Night) does a city offer per year? How many incubators from established companies are located close to startups? Answering these questions helps in assessing a city’s density of connections. Any startup will need venture capitalists, corporations, but also related startups in order to grow. Networks ensure access to capital, infrastructure and talent.

There are a variety of tools to intensify connections. The Finnish government, for instance, launched FinNode, a public information broker platform, which connects Finnish entrepreneurs to civil servants and corporations in the United States, China, Russia, Japan and India. Meanwhile, New York has unveiled its NY Digital Map in 2012, an online map plotting startups, investors and incubators across the city’s five boroughs. The tool is “a visual testament to the vibrant state of New York’s digital industry” and even allows users to review job postings.

Reputation

How many newspaper articles per year feature a city’s startup ecosystem? Does Google Search autocomplete “startup” when entering one’s city? Answering these questions helps in measuring a city’s startup reputation. A great reputation (Berlin, for instance, was recently featured as “Silicon Alley” by the New York Times) attracts both talents and capital. The downside is a rise in rental prices as well as a lack of centrally located rental property.

Policy-makers build a great reputation for a startup ecosystem when strengthening capital, infrastructure and talent availability as well as network density in a city. Credible public leaders committed to startup development also boost reputation. Examples of such leaders would be New York’s Michael Bloomberg or Berlin’s Klaus Wowereit. Certainly, the overall vibe of a city – the city’s artists and musicians from all over the world, cozy bars, restaurants and clubs as well as the mixture of historic sites and contemporary architecture – also enhance a city’s attractiveness for entrepreneurs.

If one chooses to spend the startup budget on marketing campaigns instead of directly addressing the root causes of a vibrant startup ecosystem, positive effects on the city’s young companies will, however, be short-term at best. After all, reputation follows substance.

Delivery unit and ‘stretch goals’

Once a city has assessed its strengths and weaknesses as a startup hub, specific initiatives to enhance the five key success factors outlined above must be designed. A startup delivery unit is the ideal tool to implement these initiatives. Such a unit is a group of around 10 individuals within a public administration (usually directly reporting to a city’s mayor) exclusively dedicated to implementing and encouraging all startup initiatives. Both recruited from the public and private sector and typically led by an established entrepreneur, delivery units committed to measurable impact coordinate and monitor implementation plans and inform the public at regular intervals on the city’s developments as a startup hub.

Ideally, such units deliver against a stretch goal set in the beginning of any startup initiative, such as the creation of an additional 100,000 jobs. Such stretch goals (including a variety of key performance indicators related to each envisaged action) ensure the strategic alignment of all initiatives as well as the maximum effort of all stakeholders involved.

The pro-bono-report “Boosting Entrepreneurship in Berlin – Five Initiatives for Europe’s Startup Metropolis” was published October 7th 2013. Its 2010 prequel “Berlin 2020 – Fostering Competitiveness and Innovation” outlined strategic approaches to regional development for Germany’s capital.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/15Sddkv

_________________________________

Katrin Suder – McKinsey & Company

Katrin Suder – McKinsey & Company

Katrin Suder is Director at McKinsey & Company. She currently leads McKinsey’s Berlin office as well as Germany’s Public Sector Practice. Both a physicist and linguist by training, Suder helps clients to master strategic challenges as well as to develop lean governmental administrations and innovative IT infrastructure.

–

Holger Haenecke – McKinsey & Company

Holger Haenecke – McKinsey & Company

Holger Haenecke is Manager of Professional Development at McKinsey & Company. The trained lawyer and former Engagement Manager at McKinsey & Company particularly works on talent management and organizational effectiveness.

–

Julian Kirchherr – McKinsey & Company

Julian Kirchherr – McKinsey & Company

Julian Kirchherr is Fellow at McKinsey & Company. Prior to joining the Firm, he ran an early stage startup and served as a City Councilor in Werl, Germany.

4 Comments