Slovakia is due to hold the first round of its presidential elections on 15 March, with the second round scheduled for 29 March. Ahead of the elections, Daniel Kral provides an overview of the political landscape in the country, where the centre-left party Smer-SD is currently in power with a rare single-party majority. He writes that although the country’s prime minister Robert Fico is ahead in the polls, Andrej Kiska, an ‘apolitical’ candidate, has gained a substantial share of support. He argues that Kiska’s success likely represents widespread frustration with political elites among Slovakian voters.

Slovakia is due to hold the first round of its presidential elections on 15 March, with the second round scheduled for 29 March. Ahead of the elections, Daniel Kral provides an overview of the political landscape in the country, where the centre-left party Smer-SD is currently in power with a rare single-party majority. He writes that although the country’s prime minister Robert Fico is ahead in the polls, Andrej Kiska, an ‘apolitical’ candidate, has gained a substantial share of support. He argues that Kiska’s success likely represents widespread frustration with political elites among Slovakian voters.

On 15 March, Slovaks will go to the polls to elect, in two rounds of voting, their third president since the end of communism. The President of Slovakia has comparatively little power and his/her main political instrument, which is vetoing legislation, can be easily overturned by the Slovak Parliament. Nevertheless, the post has attracted a broad array of contenders. Following liberal candidate Peter Osuský’s withdrawal from the race in late January, fourteen different candidates have been competing for votes.

Who are the candidates?

It may come as a surprise to the external observer that current Prime Minister Robert Fico, leader of the ruling leftist-populist Direction – Social Democracy (Smer-SD), has decided to run, despite the fact that he enjoys much greater political power in his current role. Although his true motives remain the subject of speculation, Mr Fico could have designs on becoming a more active president, following the lead of current Czech President Miloš Zeman.

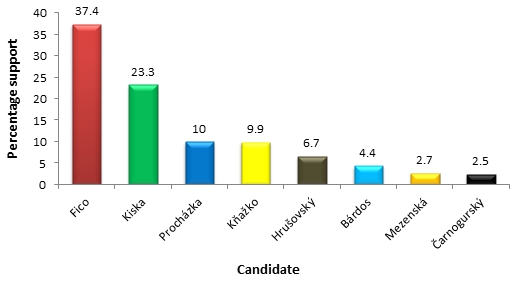

The mantra of Mr Fico’s campaign has been the need for stability and cooperation between political leaders, in order to navigate Slovakia through the tough crisis-ridden times. However, some are deeply worried that, should Mr Fico win, all the country’s national political institutions will be controlled by Smer-SD. It already boasts Slovakia’s first ever one-party government, with a parliamentary majority which rubber-stamps all government proposals and political nominations across state institutions. Nevertheless, such fears do not seem to concern Mr Fico’s broad and stable base of supporters, with polls consistently putting him first, with over 35 per cent of the vote. The Chart below shows the average preferences of voters across four polls conducted during February.

Chart: Average of four polls in February 2014 on voting intention at Slovakian presidential election

Note: Polls conducted by Focus, Polis, Median, and sme.sk

Note: Polls conducted by Focus, Polis, Median, and sme.sk

The candidate who has run the longest and most expensive campaign is Andrej Kiska, a successful entrepreneur who made his wealth in leasing companies, but is better known as a philanthropist. He prides himself on not having any political affiliations. Although his ideological credentials are rather ambiguous, his intensive campaigning appears to be paying off, as polls consistently rank him second. Indeed, one poll from mid-February put him only 3 percentage points behind Mr Fico. This has shattered the perception that Mr Fico would emerge as the undisputed victor of the first round of voting. Occasionally a target for allegedly having made his fortune through questionable business ethics, Mr Kiska’s lack of eloquence may cost him the race in the short term.

There are a number of candidates which fit on the centre-right of the political spectrum. Constitutional lawyer and former Christian Democrat Radoslav Procházka has tried to appeal to voters with his relatively young age and legal expertise, which he promises to use in order to improve Slovakia’s troubled judiciary. Milan Kňažko, an actor with political experience from the turbulent 1990s, campaigns on vague references to greater direct democracy, tackling corruption and smaller government. Former Speaker of Parliament and ‘political dinosaur’ Pavol Hrušovský of the Christian Democrats (KDH), is unlikely to receive more than a small percentage of the vote, despite being the joint candidate of the parliamentary centre-right parties and receiving support from outsiders like Angela Merkel.

The remaining candidates are, more than anything, looking for the visibility which being a presidential candidate brings. Among them are the candidate of the traditional party representing the Hungarian minority (SMK) Gyula Bárdos, the once-prominent member of KDH Ján Čarnogurský, and the most vocal anti-establishment, Eurosceptic and esoteric candidate, Helena Mezenská, MP for the Ordinary People (OľaNO) party.

Old and new trends

The key question for the race is who will face Mr Fico in the second round. Most of the other leading candidates have promised to support whoever that turns out to be. Although it appears, and Mr Fico would arguably wish, that this will be the politically inexperienced Andrej Kiska, it is too early to write off other contenders.

However, a deeper issue is that instead of a political duel along traditional ideological lines, the choice for voters will be between Fico and ‘anyone-but-Fico’ – Kiska, Procházka or otherwise. The scenario is reminiscent of the presidential run-off a decade ago, which was characterised by widespread mobilisation against the illiberal-turned-liberal Vladimír Mečiar, who made it to the second round. In this respect, the election is firmly structured around a highly polarising figure, rather than on a meaningful political discourse.

Equally important, the run-up to this election has confirmed the long-term trend of a quarrelling and incoherent centre-right. The centre-right parliamentary parties have put forward a common candidate. However, the parties continue to splinter, and ever more new movements, parties and presidential candidates have broken off from them. Moreover, a recent bargain struck between the ruling Smer-SD and KDH has resulted in the traditional main centre-right party (SDKÚ) threatening to withdraw its support for Hrušovský. Thus, instead of bringing the fractured centre-right parties together, the presidential election has further exasperated the existing cleavages between them.

The fact that an ‘apolitical’ candidate, Andrej Kiska, has been so popular reflects voters’ widespread frustration with political elites and politics in general. Anti-establishment groups, such as the liberal Freedom and Solidarity (SaS) and its offshoot Ordinary People (OĽaNO), have together captured ever growing shares of the vote in recent general elections. In the Czech Republic, the electoral success of billionaire Andrej Babiš and his ANO party in the latest general election suggests that this phenomenon may not be confined to Slovakia. It would appear that Eastern European democracies increasingly favour political opportunists who have enough money to afford full but ambiguous campaigns in which they seem to convince voters that they are distinct from ‘the establishment’.

What is at stake?

Above all, the upcoming presidential election has symbolic meaning. It is not shaping up to be a ‘watershed election’ in which the future direction of the country will be decided. Although Mr Fico may wish to increase the powers of the president should he win, Smer-SD does not have the supermajority in parliament needed to do so and none of the opposition parties would likely sign up to it.

The most dramatic impact of the election could be for Smer-SD itself. If Mr Fico wins, it is unclear who would take over as prime minister. This could bring the potential of conflict in a party which has to date managed to maintain its unity. Similarly, Mr Fico’s loss would be a severe blow to his popularity, possibly signalling the beginning of the end of Smer-SD’s hegemony over Slovakian politics.

Despite the large number of candidates, the presidential election carries a rather hollowed-out political discourse, with little change on the country’s political landscape. It has also added to frustration of the centre-right voters, as they become increasingly susceptible to political opportunists unburdened by a political past.

More than anything else, the election will be a referendum on Mr Fico and his party’s domination in national politics. This has been epitomised in SDKÚ’s campaign slogan, ‘Smer can’t have it all!’ Whether Smer-SD gets it all, and how the political actors respond to the outcome, remain to be seen.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1cqaIsN

_________________________________

Daniel Kral – University College London

Daniel Kral – University College London

Daniel Kral is a postgraduate research student in the School of Slavonic and East European Studies at University College London. His research interests include small states and the politics and economics of Central and Eastern Europe. He is currently researching the dynamics of economic adjustment to the 2008-2009 financial crisis in Central-Eastern European states. Follow him on Twitter: @DanielKral1