The European Parliament elections in Cyprus came a little over a year after the severe financial crisis which hit the country in 2013. James Ker-Lindsay writes that with the allocation of seats among parties remaining the same as it was in the 2009 European elections, public discontent was largely expressed through abstention rather than protest votes. Perhaps the biggest story of the campaign, however, was the participation of several Turkish Cypriot candidates, as well as the creation of special polling centres allowing Turkish Cypriot voters to take part in the election. Nevertheless, the turnout among Turkish Cypriots was exceptionally low at a little over 3 per cent.

The European Parliament elections in Cyprus came a little over a year after the severe financial crisis which hit the country in 2013. James Ker-Lindsay writes that with the allocation of seats among parties remaining the same as it was in the 2009 European elections, public discontent was largely expressed through abstention rather than protest votes. Perhaps the biggest story of the campaign, however, was the participation of several Turkish Cypriot candidates, as well as the creation of special polling centres allowing Turkish Cypriot voters to take part in the election. Nevertheless, the turnout among Turkish Cypriots was exceptionally low at a little over 3 per cent.

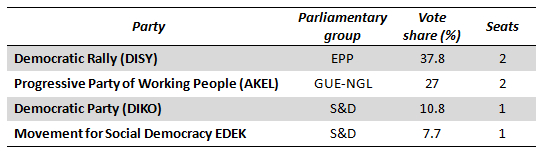

Sunday’s European Parliament elections in Cyprus, the third set of elections since the island joined the EU in 2004, yielded few surprises. As expected, the governing right-wing DISY, which is aligned with the European People’s Party (EPP), topped the results and returned two MEPs. In second place was the Cyprus communist party, AKEL, which is aligned to the European United Left (GUE-NGL), also elected two MEPs. The last two of the island’s six seats were allocated to the centre-right DIKO and centre-left EDEK; both of which are, somewhat confusingly, aligned to the Socialists and Democrats (S&D). Therefore, despite the fact that four of the six MEPs are new faces, the overall party allocation of seats remains the same as the last parliament. The Table below shows these results.

Table: 2014 European Parliament election results in Cyprus

Note: Vote shares are rounded to one decimal place. For more information on the parties, see: Democratic Rally (DISY); Progressive Party of Working People (AKEL); Democratic Party (DIKO); and Movement for Social Democracy EDEK. Full results are available here.

Nevertheless, behind these rather predictable results lie some interesting stories. Perhaps the most significant relates to turnout. Anger at the European Union stands at an all-time high in Cyprus following last year’s financial crisis that saw one of the island’s largest banks collapse and many tens of thousands of savers lose their savings. This has led to a major surge in Euroscepticism.

With no popular anti-EU party to take up the protest vote, rather in the way that UKIP has in Britain, frustration was expressed as abstention. Just 43.97 per cent of registered voters showed up at polling stations. Although slightly higher than the average turnout rate across the EU (43.11 per cent) – and considerably higher than Slovakia’s abysmal, and record breaking, turnout of just 13 per cent – it nevertheless marked a significant decline on the 59 per cent recorded in 2009. (It is perhaps worth noting that Cyprus, like several other EU members, such as Greece and Luxembourg, has compulsory voting – although there are no penalties for not casting a ballot.)

As for the actual results, ruling DISY will no doubt be pleased to see that its overall share of the vote rose to 37.8 per cent; a small 1.8 per cent increase from 2009. Although this can in part be attributed to its electoral alliance with another party, the government will no doubt be gratified to realise that after having faced the economic collapse, its support has held up so well. In contrast, AKEL saw a significant decline in its share of the vote. This time round it polled 27 per cent; down from 34.9 per cent in 2009. This would seem to indicate that the electorate – and even many of their own supporters – blame them for the financial crisis. They had, after all, been in power until just a few weeks before the crisis. DISY was merely left to deal with the mess.

At the other end of the scale, and given the concerns about the rise of extremist parties elsewhere in the EU, it is also worth noting that ELAM (National Popular Front) failed to make much headway. It received just 2.69 per cent of the Cyprus popular vote. Despite the economic situation in Cyprus, and widespread concerns about immigration, this is a long way off the 9.4 per cent received by its affiliate in Greece, Golden Dawn.

However, the biggest story of the election centres on the participation of Turkish Cypriots. In total, there were five Turkish Cypriots standing as candidates. Two were on a joint ticket with Greek Cypriots. Another two were the sole representatives of a Turkish Cypriot party. The final candidate stood as an independent. Meanwhile, for the first time, provision was made to allow Turkish Cypriots resident in the north of the island to cross over the dividing line and vote via special election centres. This potentially opened the way for 90,000 Turkish Cypriot voters to take part in the poll.

In the end, though, approximately a third of these were left off the electoral roll due to an apparent error concerning their registration. As a result, several Turkish Cypriot candidates have said that they will consider launching a legal challenge against the validity of the elections. In reality, the mistake – and there is nothing to suggest that there was a deliberate effort to keep the Turkish Cypriots from voting – will not have made much difference. Turkish Cypriot turnout was just 3.1 per cent. The vast majority heeded calls from Turkish Cypriot political leaders not to take part in the vote.

A version of this article first appeared at the Greece@LSE blog

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: J. Patrick Fischer (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/TRRC7b

_________________________________

James Ker-Lindsay – LSE

James Ker-Lindsay – LSE

James Ker-Lindsay is Eurobank Senior Research Fellow in South East European Politics at the London School of Economics. His main research interests relate to conflict, peace processes, secession and recognition. He is the author of Kosovo: The Path to Contested Statehood in the Balkans (I.B. Tauris, 2009), The Cyprus Problem: What Everyone Needs to Know (Oxford University Press, 2011) and The Foreign Policy of Counter Secession: Preventing the Recognition of Contested States (Oxford university Press, 2012). He can be found on Twitter @JamesKerLindsay