Sweden will hold a general election on 14 September. Ahead of the vote Jonathan Polk and Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson provide an overview of the polling and the platforms for each of the mainstream parties. They note that while the ‘Red-Green’ opposition parties have been leading the polls, there is some momentum for the governing ‘Alliance’ coalition and it still remains unclear what government will emerge from the election.

Sweden will hold a general election on 14 September. Ahead of the vote Jonathan Polk and Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson provide an overview of the polling and the platforms for each of the mainstream parties. They note that while the ‘Red-Green’ opposition parties have been leading the polls, there is some momentum for the governing ‘Alliance’ coalition and it still remains unclear what government will emerge from the election.

The Alliance, a centre-right coalition of four parties led by the Moderate Party, will attempt to maintain its incumbency in the Swedish general elections on 14 September. Although the Swedish economy has fared relatively well in comparison to many other countries in Western Europe, and Prime Minister Fredrik Reinfeldt and the Alliance government received positive evaluations on handling the economic challenges of recent years, the Alliance continues to trail the Red-Green bloc of the Social Democrat, Green, and Left parties in all opinion polls. Forecasting models of the 2014 election highlight this paradox: A model based on standard economic variables predicts incumbent reelection, while opinion poll-based model predicts a defeat for the Alliance.

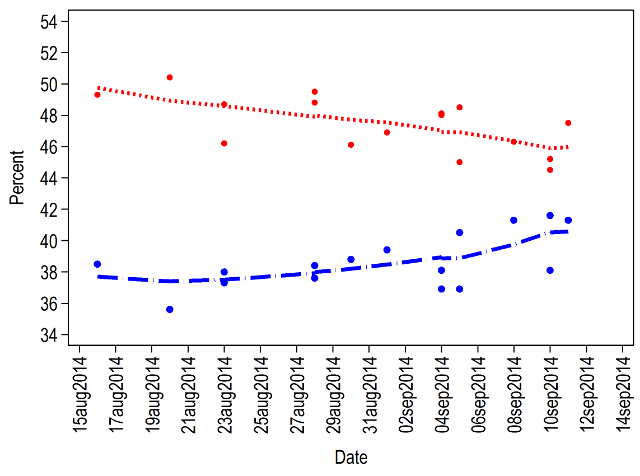

Chart 1: Estimate of vote share for Alliance parties (blue) and Red-Green opposition parties (red) in the 2014 Swedish general election

Note: The chart shows ‘lowess smoothing’ and point estimates of the electoral support of Alliance parties (blue) and the Red-Green opposition parties (red) based on opinion polling by Demoskop, TNS-Sifo, Ipsos, and Novus from 15 August to 11 September.

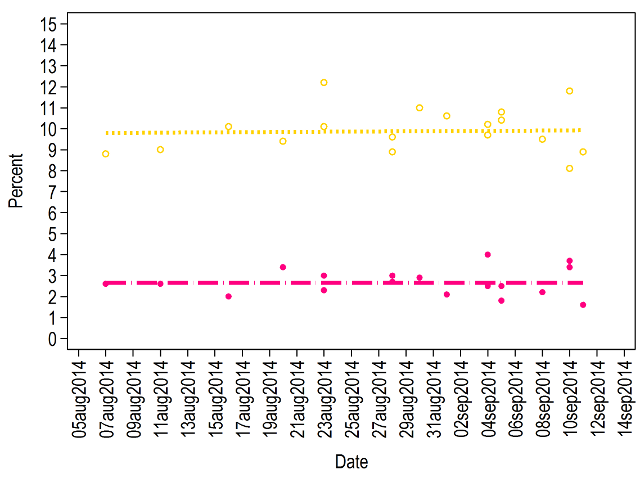

Issues such as unemployment, job creation, education and schools, and the role of private companies in the welfare sector have featured prominently in the campaign, as have questions of immigration. This latter issue is of particular interest to the Sweden Democrats, a nationalist and anti-immigration party that is expected to double its electoral support to around 10 percent (see Chart 2). Seven Riksdag parties have ruled out any co-operation with the Sweden Democrats after the elections because of the massive ideological differences on immigration issues.

Chart 2: Estimate of vote share for the Sweden Democrats (yellow) and Feminist Initiative (pink) in the 2014 Swedish general election

Note: The chart shows ‘lowess smoothing’ and point estimates of the vote shares for the Sweden Democrats (yellow) and the Feminist Initiative (pink) based on opinion polling by Demoskop, TNS-Sifo, Ipsos, and Novus from 15 August to 11 September.

In addition to potential changes in policy that we might – or might not – expect to see in a change of government, questions about the precise configuration of the centre-left or centre-right governments that could emerge after this election persist in the last few days of the campaign. Nine viable parties will compete for seats – the Feminist Initiative still has a slim chance to climb over the four per cent threshold – and none of the blocs will be able to form a majority because of the prohibition against the Sweden Democrats. This strategic context makes it increasingly difficult for Swedish voters to vote strategically, leading some commentators to speculate that this may lead to parliamentary chaos in Sweden after the elections.

Reinfeldt and The Alliance seek a third electoral period with a centre-right government and the same Prime Minister, a difficult task in many economically advanced democracies, and a feat never achieved by a centre-right government in Sweden. The inherent costs of governing have combined with the thermostatic nature of public opinion in Sweden to produce an election environment that brings the gravitational center of the electorate closer to the Social Democrats, the party that dominated Swedish politics for much of the 20th century. This tendency for an electoral reversion to the mean could help explain the diverging expectations of forecasting models based on economic voting expectations and those derived from opinion polls.

Party platforms

The four parties that make up the Alliance – the Moderate Party, Liberals, Centre Party, and Christian Democrats – issued a joint election manifesto that emphasises reforms to education based on smaller class sizes, job creation, and an increase in housing construction. The parties committed themselves to building 300,000 homes by 2020, creating 50,000 new jobs, and improving the conditions for beginning and operating a business. In addition, the parties promised not to raise corporate or payroll taxes. The joint manifesto stands in sharp contrast to the opposition, which has not created a formal coalition and issued independent manifestos.

The Social Democrats have focused on Sweden’s 8 per cent unemployment throughout the campaign, and the party’s manifesto – issued one day after the Alliance’s – promises to cut Swedish unemployment to the lowest level within the European Union by 2020. The party also seeks to increase unemployment benefits, and guarantee young people a job, training, or educational position within 90 days of unemployment. The Social Democrat manifesto also emphasises education reforms, and recommends smaller class sizes in schools and higher wages for teachers. The package of policies proposed by the Social Democrats is projected to be more expensive than those put forward by the Alliance, and the party would finance the increase in spending on welfare, schools, and jobs by increasing taxes on banks, the VAT for restaurants, and high earning individuals.

The Green Partymanifesto (one of the few translated into English) prioritises reducing climate emissions, making investment in sustainability the cornerstone of new job creation, and decreasing the bureaucratic responsibilities of teachers throughout Sweden’s schools. The Left Party strongly opposes profit making in the sectors of education and health and elderly care, and would like to see the role of private companies in these areas diminished. These issues surrounding the role of private companies and profit in formerly public sectors could cause complications in a Social Democrat led government and have contributed to ongoing questions about what a Red-Green government would look like in practice.

The pre-electoral coalition of The Alliance in 2006 marked an important exception and potential turning point for a country where post-election government formation is the norm. The Social Democrats no longer command upwards of 40 per cent of the vote and in the elections of the 21st century face increased scrutiny about how the party would assemble a parliamentary majority. A pre-electoral coalition between the Social Democrats, Greens, and Left in 2010 coincided with a pronounced drop in the opinion polls for the centre-left leading up to a second straight electoral loss. Party leader Stefan Löfven has therefore been much more hesitant to commit the Social Democrats to a particular configuration of post-electoral cooperation despite consistent pressure from Reinfeldt to do so. A centre-left government would almost certainly rely on support from the Left Party, the traditional supporter of minority Social Democratic governments, but party leader Jonas Sjöstedt has indicated that the Left would require a cabinet position within the centre-left government.

The rise in support for the nationalist Sweden Democrats creates post-electoral complications for the centre-right on the other side of the ideological spectrum. After first entering parliament in 2010 with just under 6 per cent of the vote, opinion polls project that the Sweden Democrats – advocates of a 90 per cent decrease in immigration – will receive a larger share of the vote in 2014, which would potentially make them an important actor in the upcoming legislative period. In an attempt to further distance himself and the Alliance from the Sweden Democrats, Reinfeldt recently indicated that he would be willing to continue to work with the opposition on asylum and immigration issues with the goal of isolating the Sweden Democrats. Whether the Social Democrats or the Moderates emerge as the largest party after the election, the possibility that a weak government will emerge appears increasingly likely.

Following a period of stable results in the opinion polls, the final week of the election campaign has brought new hope for the Alliance parties. Numerous polls have confirmed that the gap between the Alliance and the Red-Green opposition parties is rapidly closing, potentially because issues of economy and governability have been introduced in the election campaign at the expense of environmental and welfare issues. Late Thursday evening, most “poll-of-polls” showed a five-percentage point lead for the Red-Green opposition but positive momentum for the Alliance parties.

As a third of the Swedish voters are expected to make a party choice in the final week, and about 10 per cent make the final decision on Election Day, the remaining few days of intense campaigning may turn the general elections into a thriller.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Feature image credit: Christopher Neugebauer (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1qKoz2j

_________________________________

Jonathan Polk – University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk – University of Gothenburg

Jonathan Polk is a Research Fellow at the Centre for European Research and the Department of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg.

Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson – University of Gothenburg

Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson – University of Gothenburg

Henrik Ekengren Oscarsson is Professor of Political Science at the University of Gothenburg.

1 Comments