Why do citizens in some countries oppose austerity policies more forcefully than citizens in other states, even when the impact of such policies on living standards is relatively similar? Achim Kemmerling presents a psychological explanation for this variation in opinions across Europe. He argues that countries with a stronger belief in the ‘zero-sum’ nature of labour markets are more likely to oppose austerity measures.

Why do citizens in some countries oppose austerity policies more forcefully than citizens in other states, even when the impact of such policies on living standards is relatively similar? Achim Kemmerling presents a psychological explanation for this variation in opinions across Europe. He argues that countries with a stronger belief in the ‘zero-sum’ nature of labour markets are more likely to oppose austerity measures.

Economics is fifty per cent psychology and the rest is imagination. This bon mot sounds exaggerated, but the global financial crisis has revealed how accurate it is. The truth is that whatever approach economists adopt – be it neoclassic, heterodox or neo-Keynesian – they can never be right if the people don’t believe their narratives. If people don’t believe in the benefits of debt reduction then they will save, protest or emigrate; but if people don’t believe in the benefits of increased spending then they will also save, protest or emigrate.

Economic policies can only work if the people accept and believe the rationale behind the policy in question. A good economic equilibrium is therefore only as good as the underlying political equilibrium of accepting economic outcomes. European governments are now facing a gulf in expectations as the two equilibriums diverge.

A psychological explanation for why people don’t believe in austerity

The basic story put forward to justify austerity is that a reduction in debt will generate an economic turnaround, but why have people rejected this narrative? Some economists would say that people have rejected it simply because it is wrong, but the problem is more protracted than this. Everything depends on the individuals in question, and there are fundamental structural reasons why interpretations in Europe differ to such a large extent. Many scholars argue that the reasons lie in huge differences in national culture and norms. There is clearly some truth in these claims, but these factors are nevertheless difficult to change or evaluate.

My focus lies somewhere else, namely on the belief that labour markets are zero-sum games. This is the notion that there is an upper limit to the total number of jobs in a society, and hence that jobs cannot be generated but only redistributed. In order to give a job to a younger or unemployed person, the idea goes, you need to remove a job from someone else in society. In its dynamic version, people may even think that this upper limit of total jobs will fall as time passes, due to processes of globalisation or technological change. The belief is old, dating back at least to the Luddite movements which destroyed mechanical weaving looms in 19th century Europe.

Economists like Paul Krugman call this belief the ‘lump of labour’ fallacy. Alternatively, Jeremy Rifkin has described a similar process as the ‘end of work’ problem. Again, we can fight ideological, philosophical and empirical debates over the veracity of these claims, but the important aspect is not whether this claim is true or false, but rather whether people believe in it. It turns out that Europeans differ very much in this belief.

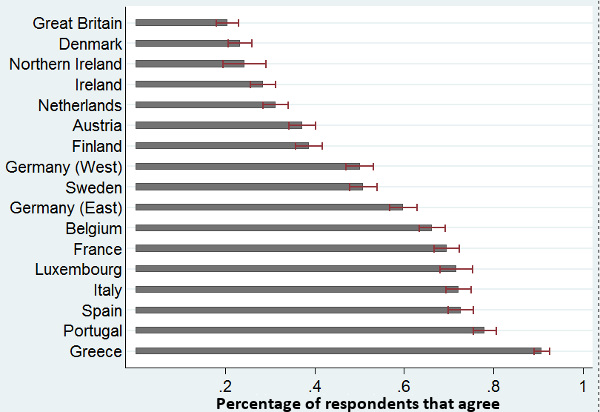

Chart 1 below shows that around a quarter of those in the UK would accept the statement that “people in their late 50s should give up work to make way for the young and unemployed”. In contrast, more than 90 per cent of Greek respondents indicate they agree with the statement. If these respondents take the view that jobs are only created by people leaving the labour market, then a preferred option will clearly be people going into retirement.

Chart 1: Percentage of citizens in selected EU countries/regions who agree that “people in their late 50s should give up work to make way for the young and unemployed”

Note: The chart was created by the author using Eurobarometer data (2001 series). The extensions to the bars represent 95 per cent confidence intervals.

What are the political consequences of this belief? For a start, people who believe that trade-offs between the old and the young exist are liable to find the policy recommendations of recent austerity packages particularly ill-conceived. Take the example of pushing back the retirement age. While this might make sense to experts who worry about the sustainability of public pension schemes and the public debt arising from demographic change, those who believe that working longer takes jobs away from younger generations will have precisely the opposite perspective.

Similar dynamics exist with other perceived trade-offs. The link between high levels of unemployment and opposition to immigration is well established. There is also likely to be opposition to policies aimed at deregulating or increasing working time regulations. Under this reading, those who believe labour markets are zero-sum games will ‘instinctively’ reject all types of labour market policies that entail an expansion of labour supply. In a recent paper I show that political preferences for people on diverse issues such as early retirement and immigration are indeed related to their belief in trade-offs within labour markets.

The role of employment protection legislation

So why do people in certain countries believe in these trade-offs? Again the answer is multi-layered and complex, but we can nevertheless identify some reasons. The belief is not restricted to those who are most directly affected such as the unemployed. Granted, if you are unemployed you are much more willing to believe in trade-offs. But people also learn about the way labour markets operate from other individuals and from other cues such as national rates of employment. Most importantly people who grow up in labour markets in which transitions between jobs, professions, or regions are difficult are much more likely to believe in these trade-offs.

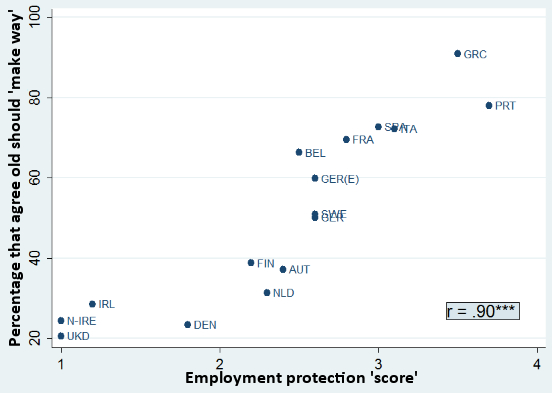

Chart 2 shows the relationship between the data in Chart 1 and the level of employment protection legislation. The latter is an indicator of how difficult it is for firms to hire and fire people, and a proxy to measure these barriers to labour market transition. The chart illustrates that there is a strong bivariate relationship: countries with a higher percentage of people believing in the trade-off are also those with more heavily regulated labour markets. More sophisticated statistical evidence shows that this finding is robust to changes in the years observed, and persists when we control for other factors.

Chart 2: Relationship between belief in the idea that older citizens should make way for younger workers and existing employment protection legislation

Note: The horizontal axis provides a measure of how extensive employment protection legislation is within a country (based on OECD figures from 2004 where a higher score signifies stricter protection). The vertical axis shows the percentage of citizens within that country who agreed with the idea that older citizens should make way for younger workers (shown in Chart 1). Chart is compiled by the author from Eurobarometer and OECD data.

Does this mean that countries should remove all laws regulating employment contracts? Clearly not. These laws show the fundamental policy preferences of the people, which can and must not easily be upset. Yet an austerity package without any popular deliberation, without any information campaign, without any components of compromise or package deals will push the will of the people and the will of the markets further apart. Ultimately, if governments and international organisations don’t learn how to communicate the necessity of reforms and renegotiate their contents, their efforts will either be in vain or excruciatingly painful.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1Bi8JCk

_________________________________

Achim Kemmerling – Central European University Budapest

Achim Kemmerling – Central European University Budapest

Achim Kemmerling is an Associate Professor of Political Economy at the Department of Public Policy at the Central European University Budapest. He has published on issues of tax policy, social and labour market policies, and fiscal federalism and worked as a consultant to the German Federal Parliament (Deutscher Bundestag), the German Society for Technical Cooperation (former GTZ, now GIZ) and the European Investment Bank (EIB).

UK model seems to be working on the jobs front so why change it? What we need is competition for jobs to drive wages up & that can’t change until we can control our borders to allow other countries unemployed to keep flooding in & taking up unskilled positions.

You’ve said we need competition for jobs, but are also advocating that we should reduce immigration (which thereby reduces competition for jobs).

As you said, the UK model is working fairly well. London is the perfect example of how a city can thrive by being a global city, where all of the world’s (or at least Europe’s) best and brightest compete for jobs and thereby drive up productivity. It works, so why are we advocating a change to it by putting barriers between employers hiring someone from another country? Make it as easy as possible for British employers to hire the staff they want from other countries and our businesses will thrive. It’s a principle that’s served the UK very well and I don’t see any reason to change it.

Are you being deliberately obtuse? Surely you realise that competition from a smaller gene pool will raise wages? An employer will not simply be able to pluck someone off the next Ryanair flight, If they want to fill vacancies they will have to compete with other employers rather than simply sucking in someone else’s unemployed. Now you refer to London as a Global City, quite right it isnt restricted to EU citizens that can barely utter a word of English but as it is at the moment the brightest & the best that create new jobs are being kept out to reduce the impact on our services, housing & infrastructure which is constantly under pressure from low skilled EU migrants. The UK isn’t Narnia we can’t keep taking them in, it isnt our fault their economies are broken, no one helped us with Subsidies, we just got on with it. We were still a net contributor to the EU project when we were under an IMF program ourselves in the 1970’s

You said competition for jobs. It’s clear now what you actually mean is competition between employers for staff.

That’s a genuinely dreadful idea from an economic perspective. You’re proposing that we artificially limit the pool of available workers so that employers will be forced to pay higher wages. That’s a recipe for completely destroying the competitiveness of British businesses. If we want to raise wages (which is not in itself a dreadful idea) then you do it with legislation, not by putting obstacles between businesses hiring the staff they want to employ.

Why economists dislike a lump of labor

Tom Walker

Review of Social Economy, 2007, vol. 65, issue 3, pages 279-291

Abstract: The lump-of-labor fallacy has been called one of the “best known fallacies in economics.” It is widely cited in disparagement of policies for reducing the standard hours of work, yet the authenticity of the fallacy claim is questionable, and explanations of it are inconsistent and contradictory. This article discusses recent occurrences of the fallacy claim and investigates anomalies in the claim and its history. S.J. Chapman’s coherent and formerly highly regarded theory of the hours of labor is reviewed, and it is shown how that theory could lend credence to the job-creating potentiality of shorter working time policies. It concludes that substituting a dubious fallacy claim for an authentic economic theory may have obstructed fruitful dialogue about working time and the appropriate policies for regulating it.

http://econpapers.repec.org/article/tafrsocec/v_3a65_3ay_3a2007_3ai_3a3_3ap_3a279-291.htm

What could be interesting in a next blog is to analyze why countries as Denmark or Netherland are far from media while having relatively high employment protection.

On other area, austerity policies are different – and probably this words have different meanings (false friends in translation jargon). This could be a reason why in some population countries reject it while others accept it..

A perfect example is Spain. Where I live.

Applied ‘austerity’ policies in Spain means to force regionals govt. to fire teachers or nurses, while central govt. contracts every year a few thousand more high scale civil servants or he continue its policy to build pharaonic – and useless- infraestructures. We had a good example a week ago , were was approved to build a station in a new High Speed railways line in a ‘city’ populated by 26 inhabitants (yes 26, this is not misspelling). Of course, nevertheless infraestructures minister is a few miles from there.

Do you imagine ducth, german or british people accepting ‘austerity’ policies how are undestood by spanish govt. ?. My guess is they would reject them as well.

That’s a well taken comment. I do agree that austerity means very different things in different places. Probably there is some commonality though, especially the problem of cutting public budgets, very often in pensions, social insurance etc. That was what I had in mind, but I do take the point.

Denmark is actually a country with relatively low protection levels (maybe because they have very few big firms, which could accomodate tougher firing laws). And the Netherlands is a fascinating case, it intelligently combines work sharing (part time economy) without creating too much burden for the social insurance schemes.

Three ideas on chart 1:

1) The opinion on early retirement could also show a correlation with a high level of youth unemployment. Getting older people to retire in order to help the young finding jobs makes much more sense if youth unemployment is a strong issue.

2) The real mean retirement age may vary considerably. This might mean that “retirement in one’s late 50’s” is perceived differently in different countries.

3) Cultural factors might play a role. All countries where a Romance language is an official language (this applies to Luxembourg, too) appear in the lower half of chart 1, whereas most countries in the upper half have a Germanic language as the dominant language. Most countries in the upper half (but none in the lower half) have predominantly Protestant traditions (and the exceptions, namely Ireland and Austria, may just cling to their neighbors with the same dominant language).

In the paper I try to account for all these possibilities, although the last one is admittedly the trickiest. The strongest impact did come from labour market regulation.

Maybe austerity programs can be explained by the fables economists were taught about those “idiot Luddites.”

Larry Summers from the unedited transcript, “Future of Work in the Machine Age” policy forum:

when I was an undergraduate at MIT in the 1960s there as a whole round of concern about this — will automation displace all the employment? And what I was taught as an undergraduate was that basically the people who thought it would were a bunch of idiot Luddites and that obviously there would eventually be enough demand and it would all sort of work itself out, and if people got more productive they’d be richer and they’d spend and maybe we needed some transition assistance, but that it was all basically going to be okay. That was what I was taught. That’s what Bob Solow thought; he was a hero and the other people were all a bunch of a goofballs was kind of what I learned. (Laughter)

That’s very true. Economists never really get at the heart of the issue. They easily disqualify this belief as a fallacy, but in my view it is a) actually not so easy to say whether it really is and b) why people worry about it, c) they do not reflect on the inherent normative choices of a society, for instance a society which wants to work less.