On 10 November, the minority government in Portugal led by Pedro Passos Coelho, which had taken power in elections in October, was effectively removed from office after losing a key vote in the Portuguese parliament. As James Dennison and Filipe Brito Bastos write, with the three main parties of the left combining to remove the government, it is expected that the next administration will be led by the Socialist Party’s leader António Costa. However they note that with the government likely to rely on the support of historically anti-euro and anti-NATO parties in the shape of the Left Bloc and Communists, Portugal has now decisively broken with the conventions that have dominated the country’s politics since the transition to democracy.

On 10 November, the minority government in Portugal led by Pedro Passos Coelho, which had taken power in elections in October, was effectively removed from office after losing a key vote in the Portuguese parliament. As James Dennison and Filipe Brito Bastos write, with the three main parties of the left combining to remove the government, it is expected that the next administration will be led by the Socialist Party’s leader António Costa. However they note that with the government likely to rely on the support of historically anti-euro and anti-NATO parties in the shape of the Left Bloc and Communists, Portugal has now decisively broken with the conventions that have dominated the country’s politics since the transition to democracy.

The Portuguese parliamentary elections of last month resulted in what turned out to be a pyrrhic, short-lived victory for the centre-right coalition of the Social Democratic Party (PSD) and CDS – People’s Party (CDS-PP). On 10 November, a majority in the Assembly, spearheaded by the Socialist Party (PS), rejected the government’s programme for their second term, effectively ousting Prime Minister Pedro Passos Coelho and his 13-day-old government. No Prime Minister had had their programme voted down in the Assembly since the even shorter-lived government of Nobre da Costa, in the late 1970s.

Indeed, the events of the last few weeks are destined to mark a watershed in Portuguese politics. By uniting the three major tribes of the left – the Socialist Party, Left Bloc (BE) and Communist Party (PCP) – António Costa, the Socialist Party’s leader, has effectively declared that political competition outweighs the continuation of the collection of unwritten political conventions in Portugal that had been designed to ward off extremism and tie the country to European integration after the Revolution.

First, the Assembly elected as its Speaker a prominent member of the Socialist Party, disregarding the convention that the role should be taken by a member of the largest party, currently Coelho’s PSD. Second, and more consequentially, for the first time the Assembly has derailed the President giving preference to the largest party when appointing a new government.

Finally, and most fundamentally, the Assembly has called an end to the era of the Arco da Governação, or Ruling Arch, by which the three centrist parties (PS, PSD and CDS) collectively sidelined the far left and agreed in principle on the most fundamental issues in the name of their shared support for European integration and the social market economy. Costa, rather than downplaying this rupture, has celebrated the end of these post-dictatorship conventions, comparing it to the fall of the Berlin wall, and stating that ‘a taboo has ended, a wall torn down, a prejudice overcome’.

The scale of these changes is perhaps best evidenced by the initial reaction to the election from the centre-right coalition, who had assumed that because of the mutual understanding under the Arco da Governação, victory was theirs in spite of not having a parliamentary majority. Some expected that even a majority could soon be theirs as Socialist MPs defected to the government. However, Costa did not stand down, despite many predicting his resignation on the night of the election and no PS members expressed an interest in defecting rightwards, despite indicating their disagreement with the direction taken by the party.

Also surprising was the willingness of the other two parties to drop their anti-Euro and anti-NATO policies in order to secure a workable left-wing majority. It is understood that Costa will uphold his country’s commitments to its creditors and Eurozone partners, while it is remains to be seen how the Left Bloc will square their participation in government with their commitment to ‘mass disobedience’ against austerity.

The undoubtedly dramatic events in Lisbon led, initially, foreign media and more sensationalist Eurosceptic commentators to denounce the appointment of the first government as a Eurozone-induced coup d’etat. Later, centre-right domestic politicians cried foul play over Costa’s manoeuvrings, with the Deputy Prime Minister calling the alliance ‘mathematically possible’ yet ‘politically illegitimate’. However, there was nothing extra-constitutional about either episode.

Indeed, the Portuguese constitution technically entitles its directly elected President to appoint whomever he sees fit, provided the electoral results are ‘taken into account’. For now at least, Costa will probably be Prime Minister for some time – the constitution bars the President from calling another election for six months and speculation that President Silva might attempt to appoint a government from outside of the Assembly would deeply contrast with his style up until now.

The major question is what kind of government will be formed – a formal coalition of the Socialist Party, the Left Bloc and the Communists or a Costa-led minority government propped up by the latter two parties in crucial votes (along confidence and supply lines). Given the President’s explicit reluctance to enable a government that committed to undermining the foundations of the post-Revolution Portuguese political consensus, the latter may be more likely.

Foxes in the henhouse or democracy redeemed?

Under the strain of intensely close political competition, long-standing unwritten conventions have been tossed aside in Portugal. Indeed, by doing so the Socialist Party have overcome the main obstacle to power for centre-left parties across Europe since the crisis – the disunion on the left between establishment moderates and anti-austerity radicals.

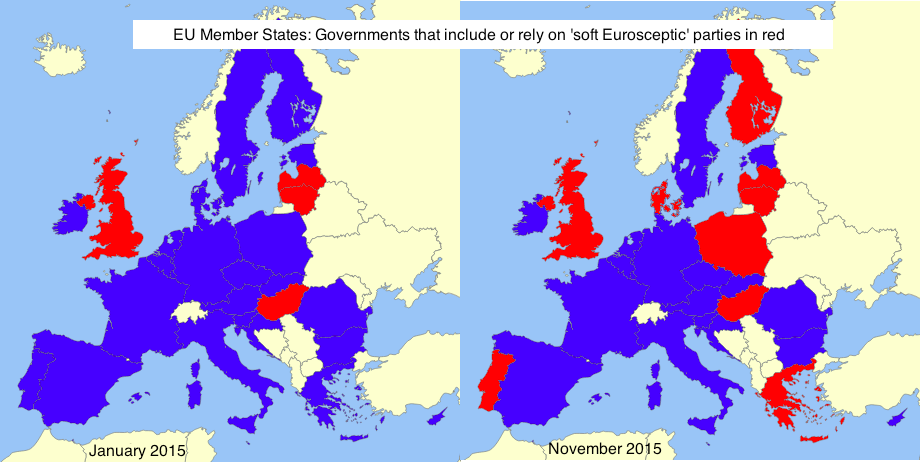

However, what seems sudden in Portugal fits into an ongoing trend in the European Union. Should the Communists and/or the Left Bloc take positions in the cabinet, Portugal would join a new but rapidly growing club of EU member states in which ‘soft Eurosceptics’ – defined by some academics as ‘qualified’ opponents to integration – prop up or form a part of the government, as shown in the Figure below.

Figure: EU member states with governments that include or rely on the support of ‘soft Eurosceptic’ parties shown in red (click to enlarge)

Note: There is no exact classification of parties that can be described as ‘soft Eurosceptic’. For the purposes of this exercise, the authors consider ‘soft Eurosceptic’ parties in governments of the EU in the two time periods to be the Czech Republic’s ODS, Latvia’s ZZS and NA, Slovakia’s SNS and SaS, Finland’s PS, Greece’s ANEL, Hungary’s Fidesz, Poland’s PiS, Portugal’s BE and PCP and the UK’s Conservative Party.

In this sense, the unprecedented events in Portugal – parliament supporting a speaker and the government not selected from the largest party, the President overruled and governing parties from outside of the Arco da Governação – form part of the ongoing unravelling of the establishment conventions and institutions that were designed to put an end to authoritarianism in Europe.

This may be no bad thing – after all, Portugal and Europe both currently have newer and extremely pressing challenges at hand, not least the Eurozone crises, so refocusing their institutions may be long overdue. Further, attempts to suppress the will of the majority are likely to fail in the long-term. However, by breaking with convention and aligning with the historically anti-euro and anti-NATO Left Bloc and Communists, as well as moving sharply to the left to do so, Costa, like an increasing number of European governments, will be forced to lead a less compromising, more self-interested government with regard to European institutions and other member states.

Previously, we argued that the centre-right coalition came first in the election because the centre-left was unable to ride the two horses of establishment pro-Europeanism and anti-austerity radicalism at once. Now Costa, via a surprising piece of his own political ingenuity and despite his electoral failings, has been given a second chance to govern on the back of an, until recently, antithetical alliance.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Harald Selke (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1SLp3Rn

_________________________________

About the authors

James Dennison – European University Institute / University of Sheffield

James Dennison – European University Institute / University of Sheffield

James Dennison is a PhD candidate at the European University Institute, Florence. His research interests include political participation, European politics and longitudinal methods. He is currently a Research Assistant for the UK in a Changing Europe initiative and teaches research methods at the University of Sheffield.

Filipe Brito Bastos – European University Institute

Filipe Brito Bastos – European University Institute

Filipe Brito Bastos is a PhD candidate at the European University Institute, Florence, where he also obtained his LLM. His research focuses on Portuguese, comparative and European administrative law and on EU constitutional law.

Just a quick query: can we define the Left Bloc as anti-euro? That seems to be more apposite for the Communists.

The map is badly wrong. Where are, say, the Lega Nord in 2009, or the NVA in 2015?

Just as a note, we should say here that the authors have since asked us to update the image to a comparison between January 2015 and November 2015 (rather than 2009 and 2015) as they felt this better illustrated their point. Whenever there has been a substantive change to a piece we like to mention this as it can change the meaning of some of the responses – such as the comment above.

Even if the caption of the image has changed, the map remains wrong. One cannot say that the NVA, the main Belgian governing party, isn’t at least “soft” eurosceptic. And one should also consider when, in the past, other and major member states had eurosceptics in government (Netherlands, Denmark, Czech Republic, Bulgaria, Poland, and Italy just to think about a few). Limiting it to screenshot of the situation in January vs November 2015 sounds misleading.