Italian Prime Minister, Matteo Renzi, has announced he will resign following defeat in the country’s constitutional referendum. We asked a number of EUROPP contributors for their immediate thoughts on the result, Renzi’s resignation, and where Italy is heading next.

- Alberto Alemanno: “The vote has killed the dream of once in a generation change”

- James Newell: “The result was not simply another anti-establishment revolt”

- Andrea Lorenzo Capussela: “Rationality imposed itself, and in large numbers”

- Silvia Merler: “Italy is now headed for a complex and delicate period of political and economic uncertainty”

- Lorenzo Piccoli: “Renzi did not have much choice but to resign”

- Jonas Bergan Draege: “Both the M5S and Lega Nord could emerge strengthened from the No vote”

- Angelo Martelli: “The determinant factor of Renzi’s defeat has been the sluggish pace of the Italian recovery”

- Davide Morisi: “The correlation is clear: Renzi’s personalisation strategy has backfired”

- Mattia Guidi: “Listening to the will of the people will be a hard task: several questions have no answer at present”

- James Dennison: “This was no Brexit-Trump moment: The package of reforms was complex and broad enough for citizens of all stripes to find cause for concern”

- Fabio Bordignon: “Renzi’s 41% – ironically, the same result he had obtained at the 2014 European election – became the symbol of his defeat“

_________________________________

Alberto Alemanno: “The vote has killed the dream of once in a generation change”

Alberto Alemanno: “The vote has killed the dream of once in a generation change”

The negative vote in the referendum came at a critical juncture for the European Union and puts Italy at a crossroads. While far from perfect, the constitutional reform put forward by the Italian prime minister sought to satisfy the undoubted need to deeply reform the country and would have been the most important reform of the Constitution since 1947. While anti-establishment and Eurosceptic actors are likely to emerge emboldened from the vote, interpreting the outcome of the Italian referendum as the next stage of Europe’s populist, anti-establishment movement – as many mainstream journalists have done – is not only factually wrong, but also far-fetched.

Indeed, as directly experienced by the Juncker Commission, Renzi himself has articulated some clear anti-EU rhetoric toward Brussels over the past year. Within the space of one month the outgoing Italian Prime Minister managed to switch from praising the EU in the island of Ventotene – where he gathered Merkel and Hollande to re-connect with the EU founding fathers – to hiding the EU flag from his private office in an attempt to defy EU bureaucracy and gain some last-minute electoral support.

Paradoxically, Renzi’s display of electoral short-termism and political machiavellanism might have damaged his support with a significant section of the electorate who – especially among the young – would have otherwise backed him. While this did not occur among Italians resident abroad (where the Yes vote won by a 25% margin), it certainly happened among those who live in the country and initially saw this government as a chance to fix the massive intergenerational failure they witnessed over the last two decades.

If the history of the Italian Republic began with a referendum seventy years ago, it will not be the outcome of the last referendum of 4 December 2016 that will put an end to the country’s existence, nor to that of the European Union. Yet, this vote has killed the dream of once in a generation change among Italians who believed that this government could eventually modernise their country.

Outgoing Prime Minister Renzi embodied young (and less young) Italians’ desire to show some bravery in reforming the country by challenging its gerontocracy. His diagnosis was right; unfortunately, his cure was denied the chance to be put to the test. Old doctors are now rushing back on stage to treat the patient.

Alberto Alemanno – HEC Paris

Alberto Alemanno is Jean Monnet Professor of EU Law, HEC Paris, Global Professor of Law, NYU School of Law and co-founder at The Good Lobby.

_________________________________

James L. Newell: “The result was not simply another anti-establishment revolt”

James L. Newell: “The result was not simply another anti-establishment revolt”

The sheer size of the No vote discredits simplistic interpretations. The result was not simply another “anti-establishment revolt”. Rather, it was the expression of a range of different types of No: a No to the specific constitutional reforms being proposed; a No to the political elites in general; a No to the current economic and social malaise; above all a No to the Renzi government. For Renzi had staked his entire future on the outcome by framing the vote as a plebiscite on him and his executive.

It was a vote that pitted against all-comers a prime minister who had been able to govern because there had been no alternative – a prime minister opposed on one side by the centre right, on the other side by the Five-star Movement (M5S), neither of which would have anything to do with the other. Now that this ‘rag bag’ of forces (to use Renzi’s own expression) has been able to come together in a straightforward yes-or-no contest, Renzi has, for the moment, been ousted from power.

This afternoon, Renzi will travel to the presidential palace to tender his resignation. But the conferral of a fresh presidential mandate on him is not to be ruled out; for his political capital has not been entirely depleted, to the contrary. He leads an increasingly “personalised” and “presidentialised” party. And if the No vote belongs entirely to none of his opponents, the 40% that voted “Yes” belongs entirely to him. It is a vote share that corresponds exactly to the proportion he won at the European elections of 2014, hailed as a great victory for his party. His problem would be holding together his coalition with the small centre parties with only fourteen months of the legislature to run.

The Chamber’s electoral law must now be revisited. Introduced on the assumption that the constitutional reforms would pass, it will lead to chaos without them. It has been seen as a gift to the M5S – though they opposed it, saying the new law concentrated too much power in the hands of the Prime Minister. In a breath-taking volte-face, they now say they want immediate elections based on the law as it stands. In that case the Chamber and the Senate will almost certainly be composed very differently – a single party having a majority of seats in the former but not in the latter.

So either the M5S are saying that they are willing, on their own, to assume the responsibilities of government, or that they want a governing alliance, and it is not clear which. Either way, it is an open question whether a party that draws support from across the political spectrum and has hitherto been a vehicle for protest, would be able to remain cohesive in face of the pressures of governing. Its experience in local government does not augur well.

James L. Newell – University of Salford

James L. Newell is Professor of Politics in the School of Arts and Media at the University of Salford.

_________________________________

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela: “Rationality imposed itself, and in large numbers”

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela: “Rationality imposed itself, and in large numbers”

The reforms that Italians rejected were ill-conceived, arguably risky, and certainly irrelevant to the main causes of Italy’s politico-economic problems. This, I would argue, is the main reason for the vote. The result had nothing to do with Europe or the euro, and much less to do with the anger of the excluded than with simple rationality. Voters were offered reforms either unnecessary or potentially damaging, and elected to turn them down.

This reading may seem simplistic, but Occam’s razor suggests treating more elaborate explanations with scepticism. The vote is hardly a clear sign of populism, in particular, for during the whole last phase of the campaign the most prominent and oft-repeated slogan of the Yes camp was that the reforms would have ‘cut armchairs’ (the distinctly populist metaphor for the equally populist argument of cutting down the political elites). Indeed, the vote is refreshing and encouraging especially when seen against the background of that campaign.

The remarkably high turnout – in strident contrast with a long-running declining trend, which recently accelerated sharply – is another good sign. After a long, acrimonious, and polarising campaign, which began in April, it probably signals also a rebuke to a political class that spent one year quarrelling about a peripheral question, at the cost of splitting the country and slowing down policy-making. The 19 million ‘no’ votes cast yesterday are a healthy lesson, therefore, which might nudge Italy’s politicians, in both government and opposition, towards more responsive and responsible behaviour.

Finally, this was certainly not a vote against reform. And although constitutional reform is not Italy’s most pressing priority, the referendum campaign suggests that a few useful changes to the constitution could elicit wide consensus. More urgent is the writing of a fresh electoral law, to replace that which accompanied the defeated reforms. I do not venture into what model will or should be taken, but trust that the debate will be more reasoned, inclusive, and reasonable than it has been on the reforms that failed yesterday: the political class now has a stronger incentive to listen to public opinion and to legislate sensibly.

In the short term, I suppose that a political coalition quite similar to the present one will approve the 2017 budget and probably govern until the end of parliament’s term. Protracted instability and untimely elections would be dangerous but are entirely avoidable: hence, they will be avoided. The only uncertainty concerns the faces of the next cabinet and the fringes of the coalition supporting it.

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela

Andrea Lorenzo Capussela is writing a book on the political economy of Italy’s decline for Oxford University Press, and is the author of a book on the political economy of the international intervention in Kosovo (State-Building in Kosovo: Democracy, EU Interests and US Influence in the Balkans. London: I.B. Tauris, 2015).

_________________________________

Silvia Merler: “Italy is now headed for a complex and delicate period of political and economic uncertainty”

Silvia Merler: “Italy is now headed for a complex and delicate period of political and economic uncertainty”

After a long and somewhat fiery campaign, we finally know the outcome of the Italian constitutional referendum. The No camp emerged victorious by a margin of almost 20 percentage points (around 60% to 40% at the time of writing). The resignation of the Prime Minister means Italy is now headed for a complex and delicate period of political and economic uncertainty.

On the political side, the President of the Republic will now need to confer the task to form a transition government, which will likely have the limited mandate to pass the budget law and amend the problematic elements of the electoral law that was drafted in tandem with the rejected constitutional amendment. After that, new elections will be held. With the opposition parties – particularly the Five Star Movement and the Northern League – strengthened by the wide margin of the No victory, the outcome of these elections are highly uncertainty.

Both these parties are strongly Eurosceptic and would probably put the theme of Europe and Italy’s membership in the EU and the euro at the centre of a campaign that promises to be highly polarised. On the economic side, the elephant in the room is the recapitalisation of Monte dei Paschi (MPS), one of Italy’s biggest banks. An operation of capital raise from private markets was due to be launched after the referendum, but in this context investors’ interest in the MPS operation could evaporate. Uncertainty may also create spillover effects on other Italian banks, who are loaded with non-performing loans and part of a strongly interconnected system.

Silvia Merler – Bruegel

Silvia Merler is an Affiliate Fellow at Bruegel.

_________________________________

Lorenzo Piccoli: “Renzi did not have much choice but to resign”

Lorenzo Piccoli: “Renzi did not have much choice but to resign”

Two years ago, at the 2014 European Parliament elections, Renzi’s Democratic Party secured over 40% of support from the electorate. This level of support was repeated in the referendum, but while 2014 was a huge victory, he is now left with the taste of bitter defeat. In the end, the ‘Yes’ vote reached more than 50% of the ballots only in Trentino Alto-Adige, Tuscany, Emilia-Romagna and in the foreign constituencies. It was a result that fell far shorter than was expected and under the circumstances Renzi did not have much choice but to resign.

Interestingly, in his resignation speech Renzi never mentioned the party of which he is secretary. This is a worrying sign for a political group that was already internally fragmented, with members scattered around a variety of different positions and even different locations during the scrutiny of the votes. Renzi’s lack of recognition for the party, however, might be due to the fact that he wants to take full and sole responsibility for the defeat.

While Renzi was clearly the figurehead for the electoral loss, the victorious side has many actors at its forefront: The Five Star Movement, Northern League, Forza Italia, Scelta Civica, and a small part of the centre-left. These five political groups have five different ideas about what to do with the electoral law, when to hold elections, and how to run the country. These discussions will now be taking place against the backdrop of growing disenchantment with Italy’s political parties, a banking crisis, widening risk premiums in Eurozone sovereign bonds and a fragile economic recovery.

Lorenzo Piccoli – European University Institute

Lorenzo Piccoli is a researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the European University Institute in Florence. He works on self-government and citizenship policies. He collaborates with the Italian NGO Unimondo.

_________________________________

Jonas Bergan Draege: “Both the M5S and Lega Nord could emerge strengthened from the No vote”

Jonas Bergan Draege: “Both the M5S and Lega Nord could emerge strengthened from the No vote”

The result of the referendum cannot solely be interpreted as support for anti-establishment politics, represented by the M5S and Lega Nord, but there is a chance that one of the main implications will be that both parties are strengthened. Voters opposed the reforms for a number of reasons. Surveys indicated that a large number of voters were unsure of what the reform package actually entailed. The strange constellation of issues in the reform, as well as the odd elite alliances on both sides, made the whole campaign complex.

Adding insult to injury, the most frequently shared news during the campaign, suggesting voter fraud, turned out to be false. Another frequently shared false news article claimed that Matteo Renzi’s own wife, Agnese, had decided to vote no. This lack of clarity in the reforms and during the campaign, in addition to reasonable critiques of the design of the reforms, probably made more voters lean toward the status quo.

However, although the reasons for the No victory are numerous, the result may be that the M5S and Lega Nord, two of the most outspoken and widely covered actors in the No campaign, emerge strengthened, at least in the short run, by the surprisingly wide margin of the No victory. This ensures these two parties have a stake in calling snap elections. The Renzi government has already passed a change to Italy’s electoral law, the Italicum, providing an automatic majority of seats in parliament for the winner of the next election. Having designed the Italicum to work alongside the constitutional changes that were rejected with the referendum, the PD will now want to change the electoral law back to a proportional system. Yet if elections are held before that, the M5S could profit from a reform they vehemently opposed just over a year ago.

Jonas Bergan Draege – European University Institute

Jonas Bergan Draege is a researcher at the Department of Social and Political Sciences at the European University Institute in Florence. He works on political behaviour and contentious politics.

_________________________________

Angelo Martelli: “The determinant factor of Renzi’s defeat has been the sluggish pace of the Italian recovery”

Angelo Martelli: “The determinant factor of Renzi’s defeat has been the sluggish pace of the Italian recovery”

The defeat in the constitutional referendum and Matteo Renzi’s decision to resign mark the end of one of Italy’s last hopes for reform and change. The outgoing Prime Minister had swept the Italian political scene with unprecedented impetus. Renzi had understood that for the centre-left to succeed the party had to abandon its traditional rhetoric and embrace a truly reformist and progressive agenda, thus, when in government, his action showed boldness and dynamism in decision making and an unscrupulous, Machiavellian-like approach in the pursuit of his goals. Many critics in these hours are pointing at his conceited and arrogant attitude to explain his failure. However, while I concede that his haughty stubbornness have enriched the enemy ranks, becoming unsustainable in the long run, it was thanks to this tenacious obstinacy that he has managed to achieve an unparalleled track record of reforms.

There are a multitude of factors behind his defeat, but the determinant aspect has been the sluggish pace of the Italian recovery. Economic growth has failed to jumpstart (due also to dampened global demand and investment), unemployment is still too high, especially among the young and in the South and the banking sector remains too fragile. The electorate has therefore punished the government transforming the constitutional referendum into an electoral opportunity to express its verdict on the Prime Minister. Renzi’s decision to attach his political fate to the approval of this key reform has probably accelerated this mechanism, but also without it, the “personalisation” would have occurred anyway.

However, if we fail to recognize Renzi’s conception of politics (which emerged lucidly in his resignation speech) as a fixed mandate to manage the res publica and achieve a clear set of goals, we will probably read the referendum result as a resounding defeat. Renzi has instead showed that by leveraging on his own strength and intuition only, in a matter of a few years, he has managed to convince 40% of the electorate against a plethora of vetocracy. An element which is even more noticeable in the vote of Italians abroad, who have largely favoured the reform (64,7% YES against 35,5% NO).

The outgoing prime minister has taken full responsibility and has now put the ball in the opposition’s court, but I struggle to see any alternative political player able to lift Italy out of the current paralysis. While an interim government parenthesis is likely to follow, Renzi’s attempt to challenge and scrap the dinosaurs may therefore just be suspended.

Angelo Martelli – LSE

PhD Candidate in Political Economy, European Institute, LSE

_________________________________

Davide Morisi: “The correlation is clear: Renzi’s personalisation strategy has backfired”

Davide Morisi: “The correlation is clear: Renzi’s personalisation strategy has backfired”

Mr Renzi’s speech on the night of the referendum clearly summarised how he approached the referendum campaign. In the entire speech, he never mentioned his own party, the Democratic Party (PD), while he focused entirely on his own responsibilities. Referring to those who campaigned for a Yes vote, he commented that “you campaigners have not lost, but I have lost”.

The personalisation of the vote has been the distinctive feature of the campaign for Italy’s constitutional reform. From the very beginning, Renzi has linked the fate of his government to the approval of the reform, promising to resign should the proposal be rejected. A promise that he promptly fulfilled, after almost 60% of Italians voted against the reform.

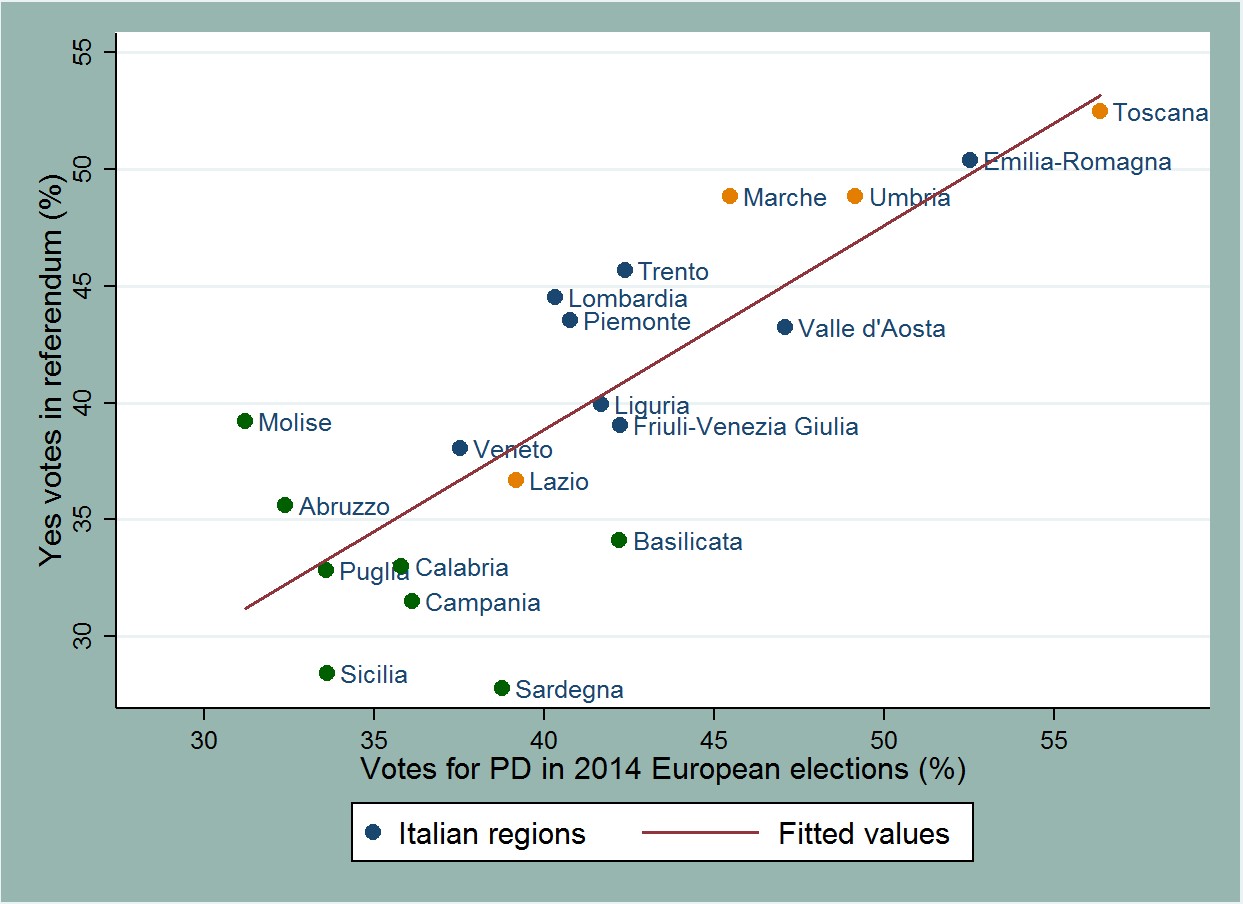

Italian voters seemed to have followed Renzi’s personalisation strategy. Instead of a referendum on the Constitution, the consultation became a clear consultation on the Government, and especially on the Prime Minister. Data in Figure 1 confirm that Yes votes in the referendum are clearly correlated with support for the Democratic Party in the 2014 European election – the only nation-wide election in which Renzi was Prime Minister. The correlation is neat: the higher the support for the Democratic Party, the higher the support for the reform.

Figure 1. Yes votes in the referendum and vote for PD in the 2014 European elections

Note. Province of “Bolzano” excluded. R2=.633, N=20

The map shows also a clear regional divide. In Southern regions (the green dots), where support for PD is lower, Italians voted largely against the reform. The share of Yes votes increased in Northern regions (the blue dots), reaching the higher share in the so-called “red regions”, i.e. the regions in which the left-wing has historically enjoyed high consensus. These regions include three regions from Central Italy (the orange dots, including Renzi’s region of Tuscany), in addition to Emilia-Romagna.

By personalising the referendum campaign, Renzi gambled all on PD’s high electoral support and high approval ratings for his government. However, PD votes by themselves might not be enough to win a referendum, as Figure 1 suggests. As our recent analysis shows, personalising the vote in a high-stake referendum proves a risky strategy. This strategy might work when government’s popularity is high, but when approval ratings go down it can backfire.

Davide Morisi – European University Institute

Davide Morisi holds a PhD in political science from the European University Institute. His research focuses on public opinion and political behaviour, with a specific focus on referendum campaigns.

_________________________________

Mattia Guidi: “Listening to the will of the people will be a hard task: several questions have no answer at present”

Mattia Guidi: “Listening to the will of the people will be a hard task: several questions have no answer at present”

The result is as clear in the overwhelming victory of the No vote, as it is uncertain in the perspectives for Italy. The remarkably high participation reinforces the perception of a plebiscite on the prime minister – a plebiscite that Renzi has lost. Not only the content of the reform, but especially Renzi’s leadership and policy-making style have been rejected. This is not something that anyone should be worried about: the people have spoken, and we must respectfully listen.

That said, for how carefully we may try to listen to the people, it would be hard to distinguish the institutional and policy goals that voters have pointed to. The victory of the no vote is yielded by a variety of political and societal actors that have little in common: the anti-system Five Star Movement and Berlusconi’s Forza Italia, the right-wing populist Lega Nord and the CGIL (Italy’s biggest trade union), the party of the Italian Left and moderate centrists like former prime minister Mario Monti.

This weird coalition has very little to propose, and the task of passing the budget law, fixing the electoral system and bringing the country to a general election will be on the Democratic Party’s shoulder. Who will be the next prime minister? How long will the next government last? Which majority will support it? Which electoral law will the Parliament pass? Will Renzi remain the party leader or will he step down? For all these questions, there is just no answer at present.

Mattia Guidi – LUISS University

Mattia Guidi is a post-doctoral fellow at the Department of Political Science and at the School of Government of LUISS University, Rome.

_________________________________

James Dennison: “This was no Brexit-Trump moment: The package of reforms was complex and broad enough for citizens of all stripes to find cause for concern”

James Dennison: “This was no Brexit-Trump moment: The package of reforms was complex and broad enough for citizens of all stripes to find cause for concern”

The key factor in explaining the victory of No was the ambivalence of the Italian electorate towards the reforms themselves. Though Italians are supportive of constitutional reform in the abstract, these reforms seemed too arbitrary, too complex and too risky to support with conviction. Attitudes to Renzi, the Euro and the political establishment were only meaningful campaign issues because of the voters’ lack of certainty over the actual proposition at hand. Not only was the package of reforms technically complex – in one poll 83 per cent of voters claimed to understand them only superficially or not at all – but they also were broad enough for citizens of all political stripes to find cause for concern.

Commentators have sought to draw parallels between this referendum and Brexit and Trump as part of a single wave of populism. However, Brexit and Trump resulted from stable electoral attitudes – long-term negative attitudes to the EU in Britain and a stable 16-year presidential cycle in the US. By contrast, attitudes to Renzi’s reforms fluctuated greatly, were characterized by their uncertainty and were guided strongly by party cues in an unstable party system.

When faced with a far-reaching and complex series of reforms, a ‘too-clever-by-half’ Prime Minister and a broad coalition of opponents – including ‘respectable’, centrist voices such as Mario Monti and The Economist – it is not so surprising that Italians chose to err on the side of caution. Renzi made reform in the name of economic efficacy the hallmark of his Premiership, yet had neither the popular nor political support needed to withstand inevitable opposition and to convince voters to take his leap of faith. Post-Lehman and Eurozone crisis, voters are less willing to give politicians the benefit of the doubt, of which there were many in this case. Ultimately surprised at his own political isolation in the face of a momentous decision, Renzi started like Blair but ended like Cameron. Instead of what would have been hailed as the ‘Third Republic’, Italian politics will now keep its hallmark ‘perfect bicameralism’. If they are serious about improving the efficacy of the legislative process, Italy’s politicians must now agree on alternative, less grandiose reforms.

James Dennison – European University Institute

James Dennison is a Researcher at the European University Institute in Florence. His work focuses on political participation.

_________________________________

Fabio Bordignon: “Renzi’s 41% – ironically, the same result he had obtained at the 2014 European election – became the symbol of his defeat”

Fabio Bordignon: “Renzi’s 41% – ironically, the same result he had obtained at the 2014 European election – became the symbol of his defeat”

It was not the perfect reform. Perhaps, it was the only possible reform, in the fragmented Italian parliament produced by the 2013 general election. It was, in many respects, a “confused” reform, which reflected the high number of compromises among the political forces. Nevertheless, it tackled some of the “unsolved” issues of Italian democracy. First of all, and more directly, the redundant bicameralism (two chambers sharing the same powers). Indirectly, and maybe more importantly, it could produce (in combination with the new electoral law) a simple and crucial result: a clear winner after the next parliamentary election.

Instead, the never-ending Italian transition is going to continue, and its destination is unclear: in fact, a striking 59% of voters rejected the “majoritarian” reform strongly wanted by the premier Matteo Renzi, who has resigned. Like Greek, British, and American voters, Italians have disregarded the fears of rating agencies, the warnings of global finance newspapers, the hopes of the European partners. They voted against the system. Against the Government. And against Matteo Renzi, who lost his plebiscite. In a tri-polar party system, a large part of the electorate voted following party positions. And Renzi’s 41% – ironically, the same result he had obtained at the 2014 European election – became the symbol of his defeat.

The clock has been turned back to the first months of 2013: no government, no leaders, no electoral rules. While the deep-rooted problems of the Italian economy are still there. Something will happen in parliament. While the most radical political oppositions are calling for early elections, the mainstream parties – and Renzi himself, as the leader of the main Italian party – are called to unravel the knot of the new government: A technical government? A grand coalition? A provisional (Christmas) cabinet? In any case, the next general election, likely to be conducted under a proportional system, will probably recreate the present situation.

It was not the perfect reform. This is the perfect storm.

Fabio Bordignon ‒ University of Urbino Carlo Bo

Fabio Bordignon teaches Political Science at the University of Urbino Carlo Bo.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Dave Kellam (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2h4RmgE