Finland will hold parliamentary elections on 19 April. Tapio Raunio previews the vote, noting that the Centre Party, which lost power after suffering a dramatic drop in support in the 2011 elections, is set to regain its position as the largest party in the country. With Finland possessing a tradition of ideologically fragmented coalitions, however, the election remains all to play for with several smaller parties vying to enter the next government.

Finland will hold parliamentary elections on 19 April. Tapio Raunio previews the vote, noting that the Centre Party, which lost power after suffering a dramatic drop in support in the 2011 elections, is set to regain its position as the largest party in the country. With Finland possessing a tradition of ideologically fragmented coalitions, however, the election remains all to play for with several smaller parties vying to enter the next government.

We are now into the final week of campaigning before Finland’s next parliamentary election on 19 April. The last elections to the Eduskunta, the unicameral Finnish parliament, were certainly exceptional, both in terms of the campaign and the result. In the run-up to the 2011 elections the problems affecting the Eurozone produced heated debates, and the EU – or more precisely the role of Finland in the bailout measures – became the main topic of the campaign.

The election result was nothing short of extraordinary, producing major changes in the national party system and attracting considerable international media attention. The Eurosceptic and populist Finns Party won 19.1 per cent of the votes, a staggering increase of 15 per cent from the 2007 elections and the largest ever increase in support achieved by a single party in Eduskunta elections. All the other parties represented in the Eduskunta lost votes.

The 2011 elections were particularly humiliating for the Centre Party. Having held the post of Prime Minister since 2003, its support declined due to a campaign funding scandal that erupted in 2008 (with many Centre MPs targets of the controversy), the economic downturn following the financial crisis, and the rise of the Finns Party. The Centre Party won a meagre 15.8 per cent of the votes, its lowest vote share since the Second World War, and ended up in opposition.

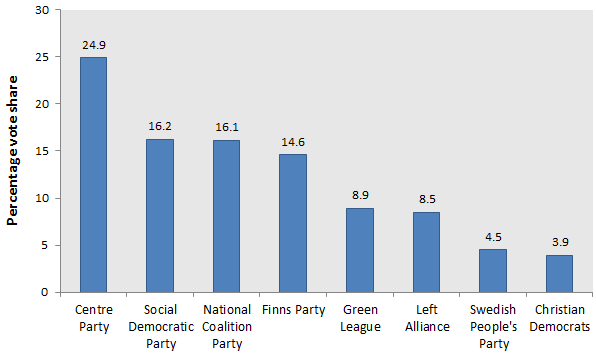

However, according to opinion polls, in terms of support the Centre Party has been the largest political party in Finland for about two years now. This revival is in no small measure thanks to the Laestadian IT-millionaire Juha Sipilä, who was elected as the party chair in 2012. A first-term MP, Sipilä probably profits from his ‘non-political’ background while his successful track record in business boosts his credibility in running the national economy. The latest polling from March puts Sipilä’s party in a comfortable lead with 24.9 per cent of support, as shown in the chart below.

Chart: Polling for the 2015 Finnish parliamentary election

Note: Figures are from the March 2015 poll conducted by Taloustutkimus. For more information on the parties see: Centre Party (Kesk); Social Democratic Party of Finland (SDP); National Coalition Party (Kok); Finns Party (PS); Green League (Vihr); Left Alliance (Vas); Swedish People’s Party of Finland (RKP); Christian Democrats of Finland (KD). Other parties not shown in the chart accounted for 2.4 per cent of support.

The ruling National Coalition Party in turn is approaching the elections in a far more subdued mood. It is broadly acknowledged that the government – which initially brought together as many as six parties but now consists of four parties after the exits of the Left Alliance over economic policy and the Greens over nuclear energy in 2014 – has failed to deliver the promised reforms, with the cabinet particularly damaged over poor handling of its top priority project, the reorganisation of social and health services.

These have been testing times for Prime Minister Alexander Stubb who was elected as the party chair last June. A manic tweeter and a self-confessed sports nut who competes in marathons and triathlons, Stubb’s youthful 24/7 exuberance does not appeal to all sections of the electorate. Perhaps more importantly, Stubb has openly admitted that domestic issues are not his strength, and with the benefit of hindsight, he probably was not the best choice as a party leader given that domestic debates have in the past few months strongly focused on dwindling economic fortunes (especially rising levels of debt and unemployment) and the associated reform of social and health services. Stubb also supports both a federal Europe and NATO membership, while attacking trade unions and favouring more market-led policies.

The Social Democrats also elected a new leader last spring: Antti Rinne, a former trade union leader with no parliamentary experience. As a finance minister, Rinne has predictably stressed job creation and economic growth – and a more active role for the government in meeting these goals. The European Parliament elections of May 2014 were disastrous for the Social Democrats, with the 12.3 per cent vote share the lowest ever for the party. Considering the financially demanding times, Rinne has needed to strike a balance between defending wage-earners benefits whilst appearing as a credible manager of the national economy. Inside the cabinet, the Social Democrats and the National Coalition Party have certainly provided entertainment through some high-profile public clashes in the run-up to the elections.

In 2011 the Finns Party clearly had an electoral incentive to capitalise on the Eurozone crisis. However, this time around the picture is rather different. After the latest elections, Soini decided to stay in opposition, justifying the decision by citing the impossibility of joining a government that was committed to Eurozone rescue measures. Yet many feel that Soini shirked government responsibility, preferring instead the safety of opposition. Now Soini has publicly declared that his party wants to enter the cabinet, and hence the Finns Party have clearly downplayed the importance of European issues.

However, the Finns Party has consistently voted against euro area bailout measures in the Eduskunta and, if invited to government formation talks, Soini must find a compromise between remaining consistent with this stance and participating in a cabinet that may have to deal with future bailouts. Interestingly, Soini has attempted to remind the electorate that the Centre Party has also voted against such measures in the Eduskunta, so a workable solution might be achievable. According to the March poll the Finns Party would finish fourth with 14.6 per cent.

Meanwhile, the smaller parties are by and large holding on to their seat shares: according to the latest poll the Greens would get 8.9 per cent, the Left Alliance 8.5 per cent, the Swedish People’s Party 4.5 per cent and the Christian Democrats 3.9 per cent of the vote. Given the tradition of ideologically fragmented surplus coalitions, none of these parties can be ruled out of post-election cabinet formation talks.

Finally, while the debate has centred largely on the health of the national economy and on the reform of social and health services, it is refreshing to see security policy also feature in the campaigns. During the Cold War Finland was characterised by ‘compulsory consensus’, wherein all parties obediently followed the policy of neutrality. The war in Ukraine and the aggressive foreign policy of Russia have livened up domestic foreign policy debates, with the (distant) prospect of NATO membership also on the agenda. This is certainly a welcome development, with politicians more willing to engage in public arguments about national and EU security policy choices.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: Finnish Parliament, Credit: NMK Photography (CC-BY-SA-3.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1DW7niN

_________________________________

Tapio Raunio – University of Tampere

Tapio Raunio – University of Tampere

Tapio Raunio is professor of political science at the University of Tampere. His research interests include the role of national legislatures and parties in European integration, the European Parliament and Europarties, Nordic legislatures and the Finnish political system.

Are these really the most recent polls? Does Finland have some law against publishing polls in the last few weeks of the campaign?

There was also another one done in March, though results are quite similar (except the Finns Party were up into third place): http://www.iltalehti.fi/eduskuntavaalit-2015/2015041119499712_eb.shtml

But yeah, polling is not very great in Finland.

There’s a factual error in the article, the Center Party’s Sipilä is not a laestadian. He’s made that clear a few times.