Syriza won the largest share of support in the Greek parliamentary elections on 20 September. Nikoleta Kiapidou gives an overview of the results and the campaign. She argues that three factors were key to Syriza managing to maintain its support: the party successfully presenting itself as a break with the ‘old’ and discredited political system of the past; the image of Syriza as a ‘fighter’ in the country’s negotiations with Europe; and its ability to maintain a pro-European stance while articulating an anti-austerity narrative.

Syriza won the largest share of support in the Greek parliamentary elections on 20 September. Nikoleta Kiapidou gives an overview of the results and the campaign. She argues that three factors were key to Syriza managing to maintain its support: the party successfully presenting itself as a break with the ‘old’ and discredited political system of the past; the image of Syriza as a ‘fighter’ in the country’s negotiations with Europe; and its ability to maintain a pro-European stance while articulating an anti-austerity narrative.

On 20 September, the Greek people were asked to vote in a general election for the fourth time since 2009, after Prime Minister and Syriza leader Alexis Tsipras resigned on 20 August. Mr Tsipras’ resignation came after only seven months in office and was prompted by the rebellion of a significant number of Syriza MPs against the approval of a new bailout deal.

In the previous election in January 2015, Syriza formed a coalition government with the minor right-wing party Independent Greeks and since then they had been negotiating for a better economic deal for the country. However, the Greek government did not manage to avoid another bailout package. The ‘No’ vote in the referendum called by the government on whether to accept the bailout agreement appeared powerless, if not pointless. The once anti-austerity parties of Syriza and the Independent Greeks signed up to a new austerity deal and the third Memorandum was eventually approved by the Greek parliament.

The results

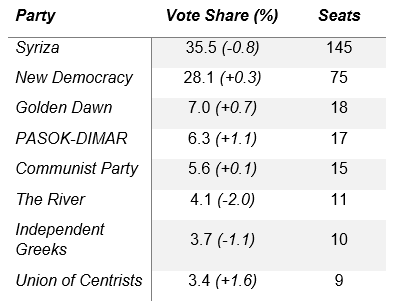

In the end, Syriza’s U-turn, contrary to the predictions of most opinion polls, did not result in a large loss of support for the party. Rather, Syriza came first with a 7 per cent lead over the centre-right New Democracy, allowing another coalition government to be formed with the Independent Greeks. Several minor parties that have become stronger since 2012 succeeded in securing their seats in parliament, which now features eight parties in total. Meanwhile voter turnout at 56.6 per cent reached its lowest level ever recorded in a general election in Greece.

Table: Results of the September 2015 Greek general election

Note: Only parties in parliament are shown. Numbers in brackets refer to the change since the previous election in January 2015. Figures from Greek Ministry of Interior; ypes.gr. For more information on the parties see: Coalition of the Radical Left (Syriza); New Democracy; The River (To Potami); Panhellenic Socialist Movement (Pasok); Democratic Left (DIMAR); Communist Party of Greece (KKE); Golden Dawn; Independent Greeks; Union of Centrists (EK).

Overall, while the polling predicted changing levels of support, the election results were not much different from the previous general election in January. Syriza, although slightly weaker, remained the biggest political power in Greece. Immediately after the referendum result, Antonis Samaras, the leader of New Democracy which supported the ‘Yes’ vote, resigned and was replaced by Vangelis Meimarakis. Mr Meimarakis maintained a relaxed public profile, but did not manage to attract enough voters. The election result found most of New Democracy’s MPs disappointed and involved in talks about ways to restore the party’s performance.

In contrast, Golden Dawn remained third and even increased their vote share by 0.7 per cent. The fact that Golden Dawn MPs had been held in pre-trial detention since 2013, accused of forming a criminal gang, and that just two days before the election their leader took ‘political responsibility’ for the murder of a left-wing Greek singer, did not seem to affect the party’s followers. Pasok came fourth and has increased its vote share by 1.1 per cent since January. However, this rise is largely explained due to the party running in alliance with the Democratic Left. The latter collapsed after joining the pro-Memorandum coalition government in 2012, but apparently retained some levels of support.

Elsewhere, the Communists maintained their power, while the centrist party The River and the Independent Greeks decreased their vote shares. The River appeared particularly dissatisfied with the result and have already stressed their willingness to re-assess their strategy. In contrast, the Independent Greeks were rather happy with the outcome and their renewed co-operation with Syriza in office, as most of the opinion polls showed that they would not even make it into the parliament.

Finally, the Union of Centrists, an old minor centrist party, entered the parliament for the first time since its formation more than 20 years ago. Popular Unity, which was created by Syriza rebels after the approval of the third Memorandum by the party, received 2.9 per cent of the vote and did not manage to gain any seats despite their consistent anti-austerity stance.

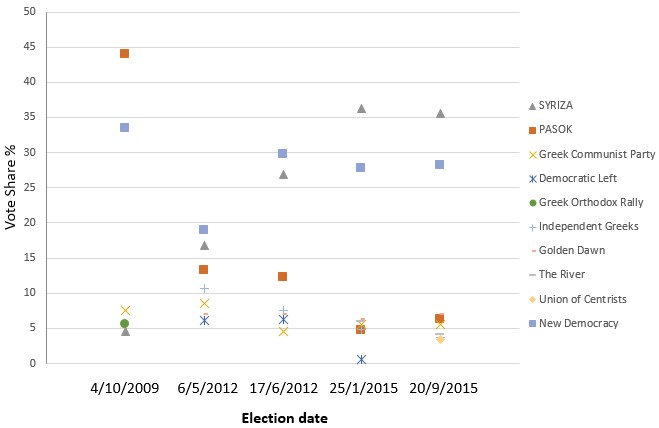

The main patterns that came out of the election are not much different from what we have seen in the Greek party system since the earthquake twin elections in 2012. As illustrated in the figure below, the election demonstrated an updated duopoly and a highly fragmented and polarised Greek party system.

Figure: General election results from 2009 until 2015 in Greece

Source: Greek Ministry of Interior, ypes.gr

A revised two-party system

Although Pasok gained some additional support in this election, the party is now considered one of the minor ones, with no hope of returning to its mainstream success as one of the two major parties in Greece (alongside New Democracy). The familiar pattern of duopoly, however, never abandoned the Greek party system; the Pasok-New Democracy divide has now been replaced with a similar contest between Syriza and New Democracy.

Certainly, the combined vote of the two major parties cannot reach the high levels that Pasok and New Democracy once enjoyed. Nevertheless, Syriza and New Democracy still manage to receive more than 60 per cent of the total vote share between them and count the biggest part of the left/centre-left and the right/centre-right as their supporters.

High fragmentation

High fragmentation is another characteristic of the Greek party system since 2012, which was also evident in this election. As the figure above shows, while only four parties managed to pass the 3 per cent electoral threshold in 2009, the number of parties in the Greek parliament increased to seven in 2012 and January 2015 followed by eight in the latest election, which is the highest number of parties in the history of the Greek parliament.

New actors, such as the Independent Greeks and The River, or old parties such as Golden Dawn and the Union of Centrists, have gained attention and benefited from the high level of electoral volatility during these years. Such parties not only get the opportunity to have their voice heard in the parliament, but also to be involved in discussions about coalition formation.

A wide ideological spectrum

Once again, high fragmentation went hand in hand with high polarisation. Just like in all the elections held since 2012, the Greek parliament consists of parties on an extremely wide ideological spectrum. With Syriza moving further to the centre-left after approving the third bailout package and New Democracy bringing together a large part of the centre-right electoral base, many of the minor parties are left with collecting protest and ‘extreme’ votes. In the new Greek Parliament one can now find parties that range from the far left (the Communist party) to the moderate centre (the River and the Union of Centrists) to the far-right (Golden Dawn).

The coalition government that emerged in January showed that the left-right divide of the Greek party system has weakened further under the fierce conditions of the economic crisis. A new pro/anti-austerity debate was born over which parties competed instead. However, with Syriza, the previously largest anti-austerity movement in Greece, signing the third Memorandum in spite of the ‘No’ vote in the referendum, this dynamic has been challenged to some extent, with some observers wondering what the purpose is of Syriza remaining in a coalition with a right-wing party. The answer is the powerful combination of features that Syriza has developed: its image as a party representing ‘the new’; its status as a party that is not pro-austerity, but is merely being ‘forced’ to be pro-austerity; and its pro-European narrative.

The old versus the new

The main factor underpinning the success of Syriza is the party’s effective use of the growing old/new political divide in the Greek party system. Falling support for Pasok and New Democracy, along with a significant decline in popular trust in national political institutions, indicated that the old two party system was already weakening before the crisis began. Syriza capitalised on this public discontent with the old political system and promoted a further division between the old and the new in Greek politics.

The party cultivated an image as a new political power which was not associated with the scandals, corruption, and elitism of the past. Indeed, popular dissatisfaction with the old political system is so deep-rooted that even Syriza’s U-turn on austerity was not enough to halt the party’s performance. The Independent Greeks are also part of the new ‘non-corrupted’ political system, and Tsipras has stated that he could even co-operate with Pasok as long as the latter let certain ‘old-Pasok’ members go. The main message of Syriza’s election campaign, ‘Let’s get rid of the old’, is evidently what Greek people wanted to hear the most.

Pro-austerity versus ‘forced-to-be’ pro-austerity

Syriza’s re-election raises interesting questions about the nature of the pro/anti-austerity divide which has characterised Greek politics since the crisis began. While in opposition, Syriza built its support on an anti-bailout platform, which it has been forced to compromise on once in office. However, the stated difference with the previous New Democracy/Pasok government, who favoured similar deals, is that Syriza ‘did not fall without fighting’. Mr Tsipras presented the failed negotiations with the country’s creditors as the ultimate struggle against European elites, who ‘blackmailed’ Greece.

After months of discussions with Europe, several impressive talks given by the former Minister of Finance, Yanis Varoufakis, and a controversial referendum, Syriza appeared to be left with no more weapons with which to fight, as did the Independent Greeks. Syriza’s approach to European negotiations, at least in the beginning, therefore seemed to be a break with that of their predecessors, who appeared more willing to accept austerity. Ultimately Syriza argued that in the end they were forced to sign the Memorandum and the narrative that they ‘did not give up without a fight’ appears to have resonated with much of the Greek electorate.

The European issue

The pro/anti-European divide has also played an interesting role in shaping party competition since Syriza’s emergence as a major political power. Although it was in a relatively weak position from 2010 until 2012, Syriza’s rise led other parties, and most importantly New Democracy, to present the party as an anti-European force who would put Greece’s EU and euro membership in danger. This discourse of fear was particularly emphasised in New Democracy’s election campaign in January 2015, but also in the referendum.

In both instances, the European issue gained significant ground as parties rushed to position themselves on the pro/anti-European and pro/anti-drachma divide. Nevertheless, Syriza has followed what most Greek people support by articulating a consistently pro-European platform, ending any suggestion the party would take the country out of the euro by accepting the third Memorandum. Syriza’s success in managing to sign a bailout agreement without losing its popular appeal is now complete. And this could only be achieved through the combination of appearing to be a ‘new’ force, presenting itself as a ‘fighter’ against austerity, and yet remaining pro-European.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: Featured image credit: Joanna / Flickr (CC-BY-SA-3.0). This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1R0GGfn

_________________________________

Nikoleta Kiapidou – University of Sussex

Nikoleta Kiapidou – University of Sussex

Nikoleta Kiapidou is a doctoral researcher at the Sussex European Institute in the Department of Politics, University of Sussex.