The extent to which British MEPs are appointed to key positions in the European Parliament can be expected to have an impact on their influence over the EU’s legislative process. In the latest article in our UK influence series, Simon Hix and Giacomo Benedetto assess how successful British MEPs have been in this respect since 2004. They note that despite a growing number of UKIP MEPs, who have not competed for many key offices, British MEPs have managed to capture a number of powerful agenda setting positions.

The extent to which British MEPs are appointed to key positions in the European Parliament can be expected to have an impact on their influence over the EU’s legislative process. In the latest article in our UK influence series, Simon Hix and Giacomo Benedetto assess how successful British MEPs have been in this respect since 2004. They note that despite a growing number of UKIP MEPs, who have not competed for many key offices, British MEPs have managed to capture a number of powerful agenda setting positions.

As part of a series on whether the UK is marginalised in the EU, two recent blogs showed that British MEPs are increasingly isolated in roll-call votes in the European Parliament (also here). However, voting records only tell one part of ‘who gets what’ in the European Parliament. Another important issue is who holds the powerful agenda-setting positions in the Parliament.

The European Parliament has two main types of power-positions. First, there are the top offices: the Bureau members, the political group leaders, and the chairs of the 22 committees. The executive Bureau comprises the Parliament’s President, the 14 Vice-Presidents (who chair the plenary sessions), and the 5 Quaestors (who look after the welfare of MEPs). The political group leaders (‘Presidents’) together determine the plenary agenda, while the committee chairs shape their committees’ agendas and play a key role in legislative negotiations with EU governments and the Commission in their respective policy areas. These top offices are assigned at the beginning of each five-yearly term and re-assigned half-way through a term.

Second, there are the rapporteurs. A rapporteur is an MEP chosen by his/her committee to write a report on a piece of legislation, the EU budget or another issue. The rapporteur shepherds the report through the committee and the plenary, and leads any negotiations with the EU governments and the Commission. MEPs and political groups compete for these powerful positions, as a rapporteur can usually influence the amendments the European Parliament proposes and hence the eventual shape of the EU law – rather like a ‘sponsor’ of a bill in the U.S. Congress.

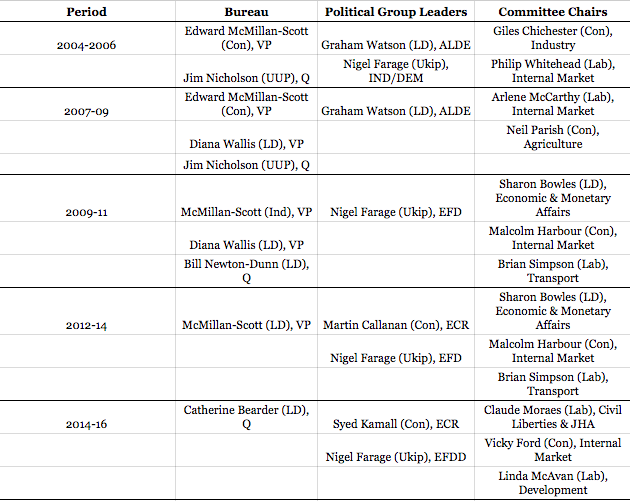

Table 1: Key offices held by UK MEPs since 2004

Note: VP = Vice President, Q = Quaestor, LD = Liberal Democrats, ALDE = Alliance of Liberals and Democrats for Europe, ECR = European Conservatives and Reformists group, IND/DEM = Independence/Democracy group, EFD = Europe of Freedom and Democracy group, EFDD = Europe of Freedom and Direct Democracy group, JHA = Justice and Home Affairs.

Table 1 shows that British MEPs have held several ‘top offices’ since 2004. Two have been Vice-Presidents, three have been Quaestors, four have been political group leaders, and UK MEPs have chaired seven different committees. Of particular note is that a Brit has chaired the powerful Internal Market committee continuously since 2004 (a critical policy area for the UK). Also, in the current Parliament, Brits chair three key committees: Internal Market and Consumer Protection (Vicky Ford), Civil Liberties and Justice and Home Affairs (Claude Moraes), and (International) Development (Linda McAvan). The other interesting point is that several UK LibDems have held top jobs, despite having fewer MEPs than the Conservatives, Labour and now UKIP.

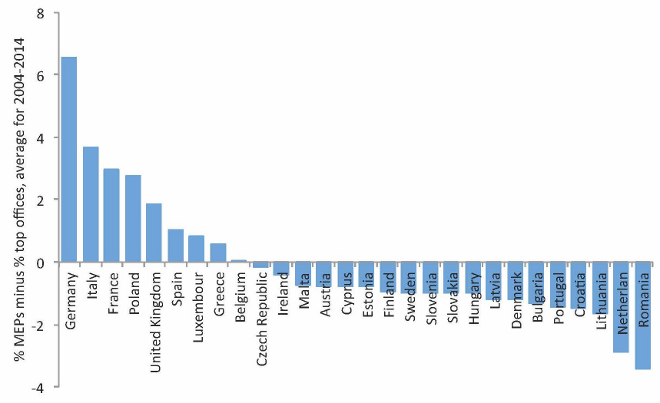

But how does this compare to other member states? One way of assessing this is to compare the percentage of MEPs each member state had in each period (2004-06, 2007-09, 2009-11, 2012-14, 2014-16) with the percentage of top offices their MEPs held. Figure 1 shows this comparison, where a member state was ‘over represented’ if it had more top offices than MEPs or ‘under represented’ if it had fewer.

Figure 1: Over/under representation of member states in EP top offices

Note: The figure shows the percentage of top offices a member state’s MEPs had in each period between 2004 and 2014 minus the percentage of MEPs it had in the same period, averaged across all five periods. For example, the UK numbers are: +0.57 in 2004 (11.22% of top offices minus 10.66% of MEPs), +2.06 in 2007, +3.76 in 2009, + 1.54 in 2012, and +1.28 in 2014, which makes an average of +1.84 (show in the figure). These data come from Giacomo Benedetto’s research.

Clearly, larger member states win more top offices than smaller member states, even relative to their number of MEPs, and the largest member state (Germany) does particularly well. This is because when a political group wins a top office, this office almost always goes to an MEP from a larger party delegation with the group, which is usually a party from one of the larger member states.

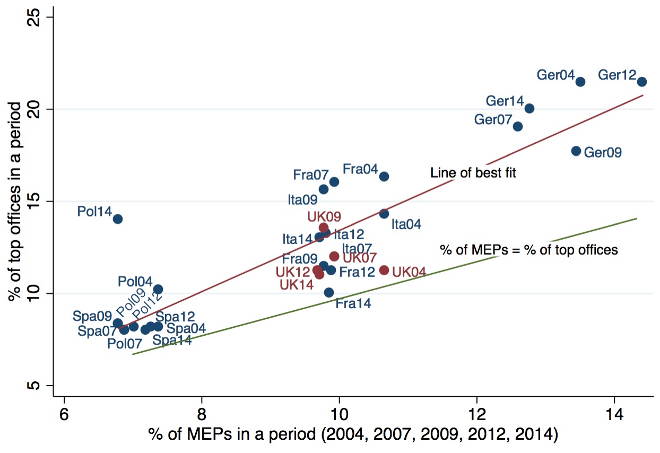

A more reasonable comparison, then, is between the larger member states, as Figure 2 shows. Here, the green line shows how many top offices a member state should have if the top offices were allocated in a strictly proportional way between the member states. Since 2004, the UK has done well compared to this baseline. However, the red line shows the average proportion of top offices won by MEPs from the larger member states. Compared to this line, the UK has done somewhat worse: winning more top offices in 2009-11, but fewer top offices than the other larger member states in every other period since 2004.

Figure 2: Representation of MEPs from large member states in top offices

Note: The green line is the 45o line, where the percentage of top offices would equal the percentage of MEPs from a member state. The large member states are ‘over-represented’ relative to this line in all five periods. The red line represents the ‘best fit’ line for the data (an OLS bivariate regression between these two variables), which captures the ‘average’ percentage of offices each member state had in a particular period, given its percentage of MEPs.

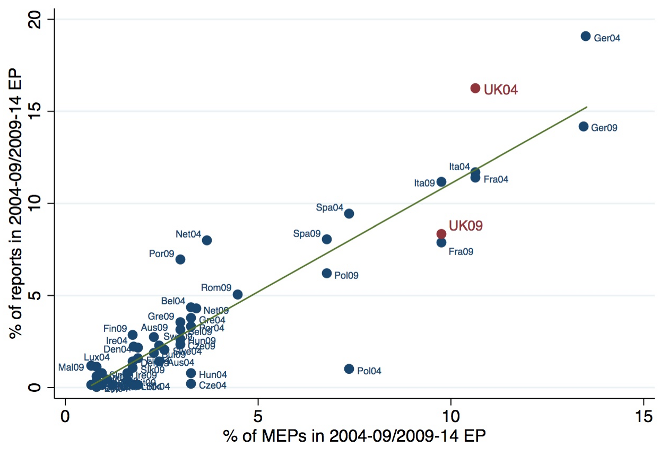

Turning to rapporteurships, Figure 3 shows the proportion of reports relative to the proportion of MEPs from each member state in the 2004-09 and 2009-04 terms. MEPs from the older member states, including the UK, are more likely to win rapporteurships than MEPs from the member states who joined in the 2000s. In fact, UK MEPs (co)authored 224 reports in 2004-09 and 180 in 2009-14. These included reports on important pieces of legislation, such as the EU Directive on Local Loop Unbundling, which liberalised the EU internet service-provider market, and on which Nick Clegg MEP was able to shape the policy in a more pro-consumer direction. In general, in terms of report-writing, UK MEPs were ‘over represented’ in 2004-09 and slightly ‘under represented’ in 2009-14.

Figure 3: Over/under representation of rapporteurships

Note: Data taken from William Daniel, and Steffen Hurka, Michael Kaeding and Lukas Obholzer. See William Daniels’ book Career Behaviour and the European Parliament: All Roads Lead through Brussels? (Oxford University Press, 2015), and Steffen Hurka et al.’s (2015) article in the Journal of Common Market Studies.

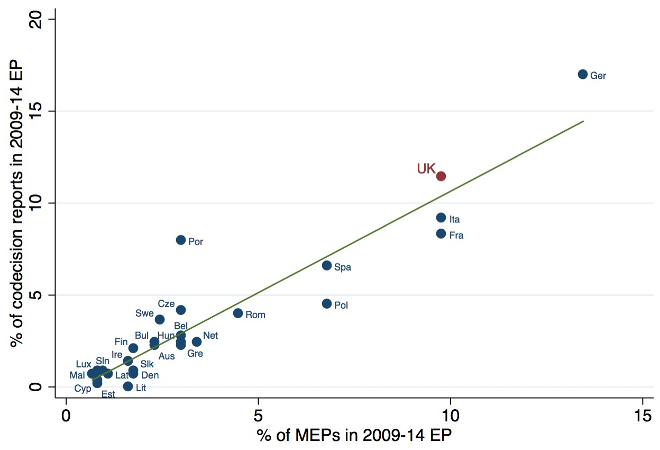

However, not all rapporteurships are of equal value. Authoring a report on a piece of legislation where the European Parliament has full legislative power, is clearly more important than authoring a report on an issue on which the Parliament has little power. As a result, Figure 4 shows the pattern for reports on ‘codecision’ dossiers in 2009-14: on all the legislation on which the European Parliament had equal power to amend and block EU laws as the EU governments in the Council. In this term, when it came to key pieces of EU law, UK MEPs author more reports than the MEPs from every other member state except Germany.

Figure 4: Over/under representation of codecision rapporteurships

Note: See note under Figure 3 for sources.

In short, UK MEPs have captured many powerful agenda-setting positions. They have been Vice-Presidents, political group leaders, and chairs of important committees. UK MEPs have also won rapporteurships on key legislation, which has enabled them to shape EU law. Moreover, UK MEPs have not been ‘under-represented’ relative to the MEPs from the other big member states. And all this has been despite the growing number of UKIP MEPs, who have not competed for many key offices or rapporteurships.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article also appears at The Guardian and UK in a Changing Europe. It gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/1oc9VD3

_________________________________

Simon Hix – LSE

Simon Hix – LSE

Simon Hix is Harold Laski Professor of Political Science at the London School of Economics and Political Science and Senior Fellow on the ESRC’s UK in a Changing Europe programme.

Giacomo Benedetto – Royal Holloway, University of London

Giacomo Benedetto – Royal Holloway, University of London

Giacomo Benedetto is Senior Lecturer in Politics at Royal Holloway, University of London.