Why are some citizens more likely to change their vote choice? Bert Bakker, Robert Klemmensen, Asbjørn Sonne Nørgaard and Gijs Schumacher show that vote switching is associated with citizen’s personality traits. Looking at UK and Denmark, they find that openness helps explain vote switching in both countries. In Denmark having a more extrovert personality is associated with party loyalty, but this does not hold for the UK.

Why are some citizens more likely to change their vote choice? Bert Bakker, Robert Klemmensen, Asbjørn Sonne Nørgaard and Gijs Schumacher show that vote switching is associated with citizen’s personality traits. Looking at UK and Denmark, they find that openness helps explain vote switching in both countries. In Denmark having a more extrovert personality is associated with party loyalty, but this does not hold for the UK.

Why do some voters “float” between different parties? This question is receiving ever-increasing attention in British politics. Some suggest that “floating” voters are characterized by low levels of interest in politics. Others have argued that such voters should not be considered “synonymous with unthinking or unprincipled” voters. Indeed, just before the General Election in 2015, David Cameron argued that such voters “want to have a good look and a good think” before they make their decision.

Yet we still don’t really know why some people change their choice. Our research revealed that citizens’ personality traits are associated with the tendency to switch vote choice or stay loyal to the party. Personality is relatively stable over time and partly heritable and so it has been associated with voting behavior and political attitudes.

Our analysis draws upon two large datasets, namely the British Household Study (2005-2009) and a unique study of Danish citizens (2010-2011). Respondents were asked on several different occasions which party they support and so we were able to calculate how often people switch their support for a party. In the UK, for instance, we measure support for political parties each year: 30 per cent of the respondents switched their support for a party at least once between 2005 and 2009.

Both datasets contained a measure of personality in the first surveys used for analysis. Personality is measured by asking respondents to rate themselves on a set of characteristics. Openness, for instance, is measured using items such as “I have a vivid imagination” which participants answer on a scale ranging from “totally disagree” (1) through “totally agree”(5). (For an example of how to measure your personality see here.)

We posit that openness and extroversion are associated with switches in party preferences. Open-minded voters are more likely to consider new ideas, imagine alternatives, and take risks. People who are less open to experience are less willing to reconsider new ideas, do not imagine alternatives as easily, and are more risk averse and so less likely to change their vote choice.

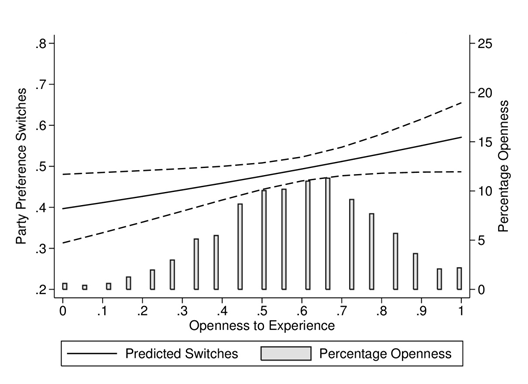

In Figure 1 you see the predicted number of switches in party support in the UK on the left-hand axis. Along the bottom axis, 0penness ranges from 0 to 1. The bars of the histogram portray the distribution of openness among our respondents. The upward slope of the solid line indicates that there is a positive association between openness and the number of switches in party preferences. Respondents that score relatively high on openness switch their party preference more often compared to respondents that score relatively low. Results in Denmark align with the results in the UK.

Figure 1: Openness and vote switching in the U.K.

Extroversion captures the tendency to be outgoing, social, friendly, and talkative. There are three reasons why we believe extroverts are likely to stay loyal. Extroverts are more likely to engage in political activities and affiliate with political parties. Extroverts are also more committed to organisations – such as political parties – over time. Besides, extroverts are more likely to be dominant and take on leadership roles. Arguably, this makes extroverts more likely to stay loyal to a party compared to introverts.

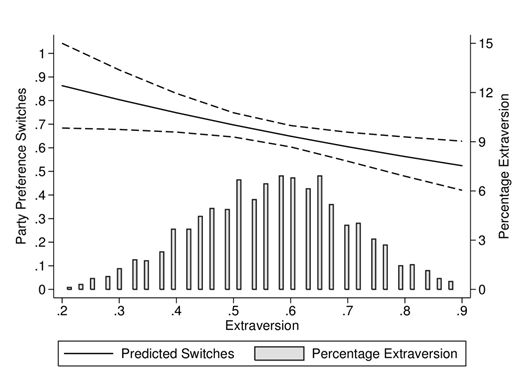

In Denmark, we find evidence for our expectation. Figure 2 projects the results in Denmark, using the same formatting as the previous graph. Citizens who score higher on extroversion change their party preference less often compared to those that score low on extroversion. In the U.K. our measure of Extraversion is less robust and we fail to find support for this claim (see here for a more in-depth assessment of the consequences of personality measurement).

Figure 2: Extraversion and vote switching in Denmark

To conclude, “floating” voters might indeed be voters who like to think about their alternatives as David Cameron suggested. We documented that they are open-minded, curious, imaginative, and willing to take some risks. Voters who are more likely to stay loyal to a party seem to be less open-minded and – at least in Denmark – more extroverted.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This piece based on the findings from a forthcoming study in Political Psychology (ungated here). It originally appeared at our sister site, British Politics and Policy at LSE. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Featured image: electoral posters in Copenhagen, 2009. Credits: Froztbyte / Wikimedia Commons.

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/25rDOmK

_________________________________

Bert Bakker is an Assistant Professor in Political Communication at the University of Amsterdam. His research is about the psychological underpinnings of political attitudes and behaviour. Twitter handle: @bnbakker

Bert Bakker is an Assistant Professor in Political Communication at the University of Amsterdam. His research is about the psychological underpinnings of political attitudes and behaviour. Twitter handle: @bnbakker

Robert Klemmensen is a Professor of Political Science (wsr) and member of the Center for Political Psychology at the University of Southern Denmark. His research focuses upon the genetic and psychological underpinnings of political behaviour. Twitter handle: @RoKlemmensen

Robert Klemmensen is a Professor of Political Science (wsr) and member of the Center for Political Psychology at the University of Southern Denmark. His research focuses upon the genetic and psychological underpinnings of political behaviour. Twitter handle: @RoKlemmensen

Asbjørn Sonne Nørgaard is a Professor of Political Science and co-director of the Center for Political Psychology at the University of Southern Denmark. His research focuses upon the genetic and psychological underpinnings of political behaviour.

Asbjørn Sonne Nørgaard is a Professor of Political Science and co-director of the Center for Political Psychology at the University of Southern Denmark. His research focuses upon the genetic and psychological underpinnings of political behaviour.

Gijs Schumacher is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. His research is about the behaviour of political parties, populism and personality and welfare policies. Twitter handle: @GijsSchumacher

Gijs Schumacher is an Assistant Professor in Political Science at the University of Amsterdam. His research is about the behaviour of political parties, populism and personality and welfare policies. Twitter handle: @GijsSchumacher

Voter switching is interesting – but I fear that the opening question ignores a significant voter behaviour

“Why do some voters “float” between different parties? ”

Is the article intended to be ONLY about voters who ALWAYS vote – and switch?

In 30 years of campaigning – including door-step canvassing – my observation is that a large number of people “switch” between a Party and Not-Voting.

i.e. the disillusioned voter withholds support from his/her traditional Party.

This may well co-incide with supporters of another Party, previously disillusioned, being newly energised.

“Switching” in actual voting may be an illusion. (see Surveys below)

If so, this should send a different message to Party strategists (and possibly Polling Organisations about their methodologies).

Perhaps Parties and Commentators should re-consider the notion of “middle ground” and “appealing to the centre” – which too often comes across as lacking substance or coherence – for anyone !

It is actual votes that win elections – not %.

Turnout is another component – and can be variable between elections.

Surely this supports the thesis that people “switch” through a phase of Abstention – with a nod to some being motivated while others become de-motivated?

For Party strategists and policy makers, this might mean that the Party’s Policy is still “right”.

Party supporters just aren’t convinced.

Perhaps the Opposition has been successful in mis-characterising the Policy.

(The Policy may need tweaking or it may need re-framing)

The studies above seem to be based on surveys between elections.

For the voter this is “cheap”.

There is no cost to answering a Survey and contradicting a previously espressed view and no effort required.

Hence Surveys are quite likely to suggest “switching” – as headlines change and issues re-presented in different contexts.