The result of the election in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania on 4 September, where Angela Merkel’s CDU only managed third place, has been interpreted by some observers as a sign that the German Chancellor could be in danger of losing power in next year’s federal election. Ed Turner writes that there is a serious risk of over-interpretation as far as the result is concerned, with Merkel still in line to retain her position as Chancellor in 2017.

The result of the election in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania on 4 September, where Angela Merkel’s CDU only managed third place, has been interpreted by some observers as a sign that the German Chancellor could be in danger of losing power in next year’s federal election. Ed Turner writes that there is a serious risk of over-interpretation as far as the result is concerned, with Merkel still in line to retain her position as Chancellor in 2017.

Land (state) elections have a high profile in Germany. They serve a dual purpose: on the one hand, they elect a Land parliament and then government, responsible for legislation in a range of policy areas – most significantly, education – and implementation of national legislation in numerous others. On the other hand, the Land government sends representatives to Germany’s national second chamber, the Bundesrat, which has a veto on any legislation that affects the Länder (states).

That being said, Mecklenburg-West Pomerania might have been perceived, to some extent, as a rather sleepy backwater, and its elections would not always have the highest profile. It stretches from the picturesque, sleepy state capital, Schwerin, through to the Hanseatic cities of Rostock (a major port and seat of an old university), Greifswald, Wismar and Stralsund.

It encompasses the island of Rügen, with its varied flora and fauna, a large number of lakes, and perhaps best known, its sandy beaches stretching along the Baltic coast towards the Polish border. Its population numbers just 1.66 million, thinly spread around the largely rural region, and the biggest industries are agriculture, fishing and maritime areas, and tourism. Unemployment, at 9%, is somewhat above the federal average of 6.5%, and youth unemployment, at 12.1%, is the highest in the country.

Politically, though, the significance of the election on 4 September was heightened by the fact the state is home to Angela Merkel’s constituency (including Rügen, Stralsund and Greifswald), and it was also home to the first formal coalition between the Social Democratic Party (SPD) and the successor party to the East German Communist Party, at the time known as the Party of Democratic Socialism (PDS) and now called the Left Party (Die Linke). On a darker note, in 1992 the Land attracted notoriety following arson attacks on accommodation for asylum seekers in the Rostock district of Lichtenhagen, and the far-right NPD won seats in the Land parliament in both the 2006 and 2011 elections.

In the Land election campaign, the SPD (which had governed as the senior partner with the Christian Democratic CDU since 2006) focused strongly on the popularity of its state premier, Erwin Sellering, while the CDU struggled to make headway under Lorenz Caffier. Although early polls pointed to a lead for the CDU, towards the end of the campaign there were clear indications that the SPD had taken a clear lead and the CDU would struggle to make second place behind the right-wing, populist AfD (Alternative for Germany).

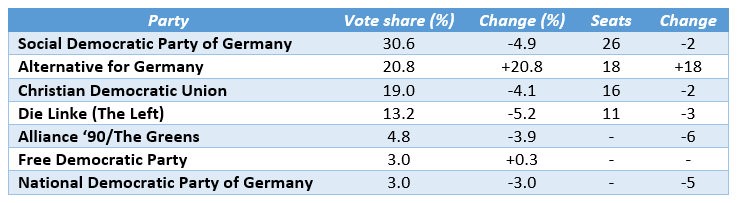

The actual results certainly caused serious ripples through the German political scene. As the table below shows, the SPD topped the poll with 30.6% (5% down on 2011); the AfD, standing for the first time in a Land election, polled 20.8%, and the CDU came a miserable third with 19.0 (-4%). The Left Party also fell to 13.2% (-5.2%). Both the Greens (4.8%, -3.9%) and the NPD (3.0%, -3%) failed to make the 5% hurdle for representation, while the Liberal FDP, with 3.0%, also failed to win any seats.

Table: Result of the 2016 election in Mecklenburg-West Pomerania

The dominant media narrative on election night was that these results, with the relative triumph of the AfD and a humbling defeat for the CDU, constituted a humiliation for Angela Merkel on her home turf, and in particular a reflection of the unpopularity of her policy (at least, the policy of 2015) of relative openness towards refugees. The staunchly conservative Bavarian Christian Democratic Party, the CSU, was almost gleeful in pointing to a “clear signal in Berlin”, and demanding faster deportations and a cap on the number of refugees.

Horst Seehofer, the CSU’s leader, talked about a “disastrous result” and a “dangerous position for [Christian Democracy], and the Bavarian Finance Minister and a possible heir to Seehofer, Markus Söder, commented that “Instead of [Merkel’s famous comment on refugees] saying ‘We can do it’, we need to say ‘We have understood and we will change it’”. Senior SPD figures chose to emphasise Sellering’s success and popularity, although one of its deputy leaders, Ralf Stegner, suggested that the CDU had been punished for opportunistically “fishing in brown [i.e. far right] waters”.

As ever, the election has been thoroughly analysed by Forschungsgrupppe Wahlen and Infratest dimap. It is possible to construct a case laying the blame for the defeat squarely at Merkel’s door and from that point to a strategic need for the CDU/CSU to reposition itself in a more conservative fashion, as the CSU urges. Such critics would highlight the fact that the AfD’s support base went beyond those associated with far right support in recent times: not only did it win the support of 33% of working-class voters and 29% of unemployed voters, but also 27% of the self-employed. It did better amongst those with lower-level qualifications (26%) than minimal qualifications (18%), and also 13% of the votes of those with degrees.

They would note that the public assessment of Merkel’s refugee policies was highly critical, and not just amongst AfD voters: 85% agreed with the statement that “The number of refugees should be limited in the long-term”, 46% that “more is done for refugees than the indigenous population”, 62% that “because of the influx of refugees, the influence of Islam in Germany will become too great”, and 50% that “the way we live will change too much”. Such views received near-unanimous support from AfD voters. Merkel’s satisfaction ratings nationally were at 47% in August, a far cry from the overwhelming ratings of yesteryear. All this seems to have led to a position where the CDU’s drift towards the political centre, under Merkel, has allowed the AfD to establish itself securely in the German party system (much in the way that Gerhard Schöder’s welfare cuts allowed the Left Party to flourish).

But there is another view, forcefully put forward, for instance, by the pollster Manfred Güllner, that attributing the AfD’s success to Merkel and proclaiming that her days are numbered is not justified. He points to polling evidence that, in a federal election, the CDU in Mecklenburg West Pomerania would have scored 33% rather than 19% (and come top); in this view the result simply points to the weakness of the local CDU in the Land. Such a view is supported by the fact that issues other than refugees (such as social justice – 53% – and the economy and jobs – 44%) were considered decisive by voters – the refugee question being named by just 20%.

It can also be argued that, in state elections where Merkel’s CDU has lost (Rhineland-Palatinate and Baden-Württemberg would be examples), another candidate has been better able to mobilise centrist voters on a Land level, but these will return to the CDU at a national election. Güllner argues that the AfD only gained support from the “minority of eligible voters [12.6%] who were always susceptible to anti-foreigner, racist, right-wing radical views”, and certain trends support that assessment: for instance, the AfD, like many right populist and far right parties, did far better amongst men (25%) than women (16%). Indeed, across Germany the assessment of Merkel’s policy on refugees is not overly negative: in August, 44% thought Merkel was doing a good job, 52% disagreed, and amongst CDU/CSU supporters, 66% supported Merkel’s policies. The CDU would still top the poll at a federal election with 35% of the vote, and there is no clear internal challenger or obvious successor to Merkel as party leader and chancellor.

In summary, the Mecklenburg-West Pomerania poll runs a serious risk of over-interpretation, notably by those with a particular, anti-Merkel or anti-refugee axe to grind. However, it would appear that the days have finally passed where there is, according to the imperative of one-time CSU grandee Franz-Josef Strauss, “no democratically legitimated party” to the right of the Christian Democrats, and the AfD has established itself in German politics, with entry into the national parliament only a matter of time.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics. Image credits: Dirk Vorderstraße (CC BY 2.0)

Shortened URL for this post: http://bit.ly/2cmVZUB

_________________________________

Ed Turner – Aston University

Ed Turner – Aston University

Ed Turner is Senior Lecturer and Head of Politics and International Relations at Aston University, based in the Aston Centre for Europe. He has written widely on German party politics and federalism.