People who live in regions that receive high levels of EU funding might be expected to have more positive attitudes toward the EU. However, as Adam William Chalmers and Lisa Maria Dellmuth demonstrate, this relationship is not as simple as it might appear. Drawing on a recent study, they illustrate that a region’s needs make a large difference to the effectiveness of EU funding in building public support: where funding meets a clearly defined need for the local population it has a far more positive effect.

People who live in regions that receive high levels of EU funding might be expected to have more positive attitudes toward the EU. However, as Adam William Chalmers and Lisa Maria Dellmuth demonstrate, this relationship is not as simple as it might appear. Drawing on a recent study, they illustrate that a region’s needs make a large difference to the effectiveness of EU funding in building public support: where funding meets a clearly defined need for the local population it has a far more positive effect.

Public support is central to the functioning of the European Union. Yet over the past decades, the EU has become increasingly publicly contested, severely limiting its ability to solve problems effectively. A growing number of academics and policy-makers have become interested in public support towards the EU, however, we know little about what the EU itself can do to shape public support.

In a recent study, we examine when, how, and why the EU is able to shape public support for the EU through spending. The answer to these questions is critical to our understanding of the determinants of public support for the EU, the ability of the EU to legitimise itself through public policies, and the controversy about fiscal redistribution through the EU budget now taking place.

Many academic studies show that the more EU spending that countries and regions receive, the more citizens in these countries and regions support the EU. But existing studies linking EU spending and public support focus on net beneficiary status and not on those EU funds that can be identified by citizens as flowing to their immediate living environment: the European Structural and Investment Funds (ESIF) flowing to EU regions. Hence, most studies tend to overlook the fact that the EU targets specific economic issues in specific EU regions such as Greater London, Bavaria, Liguria, and Catalonia. Instead, previous work on EU spending and public support lumps together any number of spending policies carried out by the EU.

In our study, we argue that the amount of spending is only part of the story. Drawing on insights from the policy feedback literature, we show how the impact of ESIF funding on support for the EU is moderated by a region’s economic need. The better the fit between how EU money is spent and a region’s economic need, the more citizens will support the EU. Results from a statistical analysis provide support for our argument.

Our theory

Our argument is that understanding the impact of the EU’s spending policy on support requires a nuanced approach to the degree to which spending is appropriate given regional economic need. We assume that individuals care about whether public capital is spent appropriately given social and economic need in that individual’s region. The extent to which the money transferred accommodates the needs of a region will influence whether the amount of money transferred influences the support for the EU of people living in that region.

We also expect the nature of spending policies to affect how likely it is that the fit between spending and economic need matters for public opinion formation toward the EU. We distinguish between distributive and redistributive spending. Distributive policies involve spending on public goods, like public land management, and transportation, where costs are diffuse with no clear winners or losers. Redistributive policies include spending on so-called private goods, like in the case of human capital spending or other non-contributory welfare programmes. As redistributive spending is relatively salient and characterised by high conflict when compared to distributive spending, we expect it to be more likely that EU funding can make people support the EU more in redistributive spending areas.

Key findings

Drawing on a unique individual-level data set encompassing 127 EU regions in 13 member states during the period from 2001 through 2011, we compare the effects on support for the EU of EU spending targeting across policy areas, regions, and over time. We examine spending targeting employment, social inclusion, transport, infrastructure, agriculture, energy, and environment.

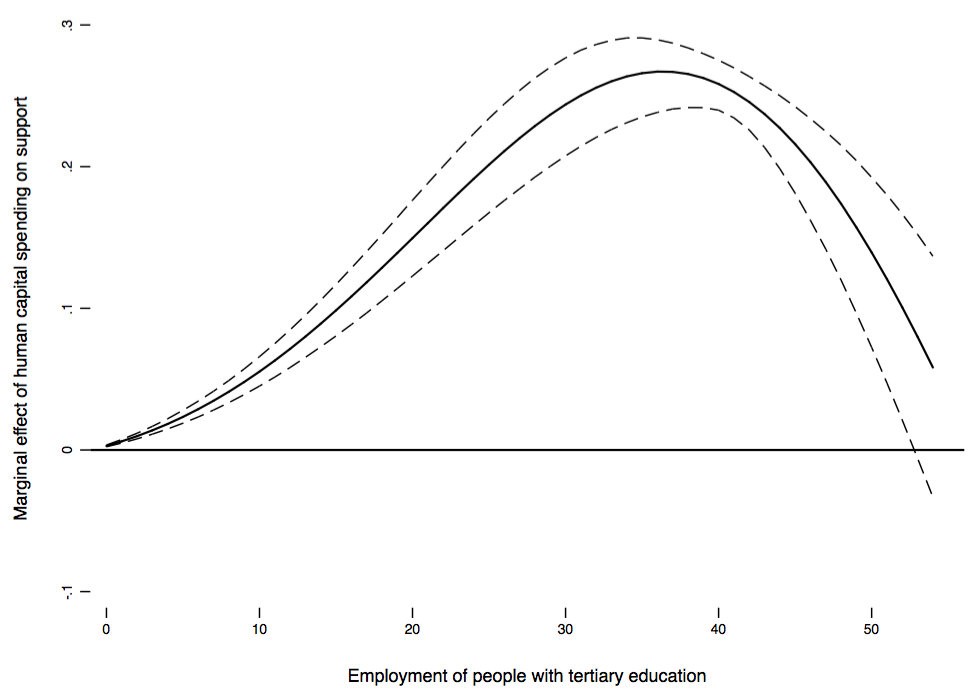

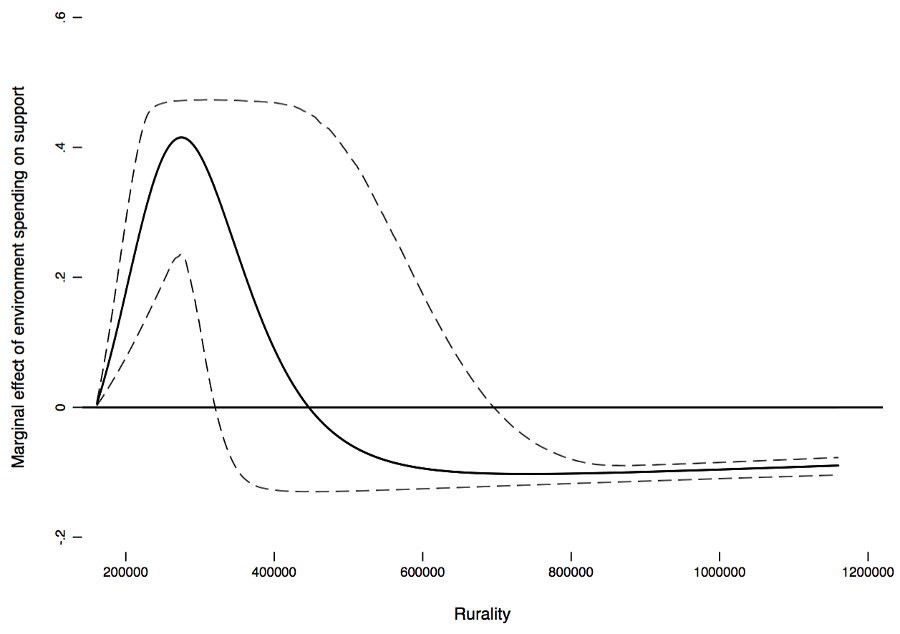

We have two main findings. First, there is strong evidence that the EU can improve public support in regions where the fit between economic need and spending is better. Second, EU spending has a larger effect in redistributive spending areas (e.g. human capital, transport, infrastructure) than in distributive spending areas (e.g. energy and agriculture). Figure 1 illustrates these effects for our three redistributive spending areas.

Figure 1: The marginal effect of human capital, transport and environment spending on public support for the EU in different areas

Note: For more information on these figures, see the authors’ accompanying journal article.

Figure 1 shows three main results. First, the top chart illustrates that human capital spending increases public support for the EU in regions with relatively low levels of tertiary employment, i.e. with greater need for spending. In regions with less need for human capital investment, spending has a weaker but still positive effect on support for the EU. Second, the middle chart shows that the effect of fiscal transfers to infrastructure and transport on support for the EU is positive in regions with relatively few motorways, that is, rural regions with relatively poor infrastructure. In regions with a relatively tight net of motorways, the link between investment in infrastructure and support is still positive but weakened. Finally, in the last chart, we can see that environmental spending has a positive effect on public support for the EU only in relatively urbanised regions where need is greatest.

Significance

Our findings have both academic and societal implications. To begin with, they mark an important advance on existing scholarly research. Economic theories of support for the EU need to be substantially refined to identify the impact of distributional consequences or economic benefits on attitudes toward the EU.

Overall, the EU is found to be able to shore up public support in its institutions through spending policies – but only if spending is needs-based. Needs-based spending has an even greater effect on public support in relatively salient policy areas. Yet the EU is not unique in the difficulties it faces in shoring up democratic legitimacy in its institutions through policy-making. In regional and international organisations other than the EU, organisational legitimation strategies that seek to enhance public support through policy are typically not linked to spending but to other forms of policy output such as soft law or providing stakeholders with access.

As research has shown, public support for regional and international organisations is of widespread relevance, and is just as important for organisations like the United Nations, the International Monetary Fund, and the Common Market of the South (Mercosur) as it is for the EU. As such organizations are increasingly becoming the object of contestation, research about how and when they can enhance public support becomes more relevant.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, and not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Adam William Chalmers – King’s College London

Adam William Chalmers – King’s College London

Adam Chalmers is Lecturer of European Political Economy at King’s College London. His research focuses on interest group politics, the European Union, and financial regulation.

Lisa Maria Dellmuth – Stockholm University

Lisa Maria Dellmuth – Stockholm University

Lisa Dellmuth is Associate Professor of International Relations at Stockholm University. Her research focuses on fiscal redistribution, European Union politics, and public opinion and legitimacy in regional and global governance.

“Public support is central to the functioning of the EU”

Interesting assertion, but I’m not sure this is true. The EU is largely built on the foundations of ‘elite’ support: it’s the votes of ministers and party leaders that determine the Brussels agenda, not the support of ordinary citizens. Witness the votes on the EU constitution in Netherlands and France: they simply repackaged the proposals and made sure the next time the voters didn’t get a say!

Every state’s participation in the EU relies on public support for that participation. Of course it’s important for European integration that people support the process. To give just one glaring example, almost all of the states that have joined the EU in recent history held referendums before they did so. The UK held a referendum after joining and also held one on deciding to leave. Other states (Norway) have held referendums on joining and decided against it. Any suggestion that the EU could continue to function without public support would be extremely wide of the mark.

Since when has the EU per se ever given a damn what the citizens /voters think or want.

Oh for goodness’ sake Karl, of course EU politicians care what people think. You do realise we go to the bother of holding European elections every five years? That a large chunk of EU states have held referendums on their membership within the last 15 years? That every EU state in unison has respected the EU’s Brexit vote and promised to put it into practice? (and so on and so on)

It is possible to have an adult conversation about the EU and be critical of it. We really don’t need to make exaggerated pantomime-calibre arguments every five seconds.

Really interesting premise and findings. The European Commission is now beginning to look more seriously at how it communicates the benefits of its ESIF investments in ways which beneficiaries can relate (much like this research, rather than just focussing on the organisations which apply for funding). My personal feeling is that is one of the many reactions to Brexit, though seems long over-due as an area of focus.

I have been grappling with understanding the outcome of the UK EU referendum results, in that some of the regions which benefit the most (Cornwall, Wales, NE England) voted to leave (some describe this as turkeys voting for Christmas) and of those regions that voted to stay, such as Scotland and London, there were likely many other contributing factors. EU funding most likely wasn’t high on the list of voters given it makes up such a small proportion of economic development budgets in those regions and the type of eligible activities are not that visible to the general public.

All ESIF programmes in the UK can be described as redistributive though (whether in anti-EU voting Wales or pro-EU voting Scotland) – so maybe this research goes some way to pinpoint why “turkeys vote for Christmas”- in that people or SME owners (end beneficiaries to put in EU speak) don’t agree with how the EU funds are used or don’t see a personal benefit (i.e. maybe there are other areas of greater priority to local people). From a regional policy perspective though that throws up a whole lot of issues. Delivery of ESIF is, of course, devolved to national or regional administrations to deliver and award though within a pretty strict/heavy EU framework of rules. Inevitably there are areas of ESIF focus which may not be regional or national priorities or where they might not choose to put their available match funding into without the need to spend EU funds. Possibly ESIF works well where priorities are aligned but it would be difficult for any region not to be able to sign up to the ambitions of Europe 2020 the economic strategy behind ESIF. Possibly in richer countries like the UK, where the scale of EU regional funds has been reduced in recent programming periods, it has little impact on public attitudes towards the EU. Fully understanding the UK EU referendum result in this context, may take time in terms of research but is critical for the future of EU regional policy.

In the past, structural funds, for example, have been essential to mainstreaming the horizontal themes of “equality” and “sustainable development” into organisations which have applied for funds. It is probably going to be one of the many policy legacy areas which will have been permanently changed in the UK as a result of structural funds. Looking to the post-2020 environment, there is a need for the next big idea to ensure ESIF has continued impact. However, looking a bit deeper at this disconnection between the EU and UK regions which voted to leave but are big recipients might be a good place to start.

There was a report in the Guardian after the Brexit vote looking at the Welsh valleys and their EU support. An age factor came to play. EU supported motorways enabled the young to shoot down to Cardiff, the new shopping centre needed cars, no public transport and so town centre died. The old regretted these changes and fused that as an Leave vote. With the rise of populism across the EU I think pure economic studies will no longer help, a far more sociological and cultural viewpoint is required.