The problem of ‘welfare tourism’ has been raised by several politicians across Europe, with some arguing that immigration from other EU countries can create a burden for welfare systems. Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen and Gabriel Pons Rotger present results from a recent study of the impact EU immigration has had on welfare spending in Denmark. They find that between 2002 and 2013, EU immigrants made a significant positive net contribution to the country’s public finances.

The problem of ‘welfare tourism’ has been raised by several politicians across Europe, with some arguing that immigration from other EU countries can create a burden for welfare systems. Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen and Gabriel Pons Rotger present results from a recent study of the impact EU immigration has had on welfare spending in Denmark. They find that between 2002 and 2013, EU immigrants made a significant positive net contribution to the country’s public finances.

Copenhagen, Credit: RobinTphoto (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)

The relationship between EU immigration and the British welfare state was one of the main themes of the UK’s EU referendum campaign. The participation of EU citizens in the British labour market – and their rights to welfare benefits – sat at the heart of a heated, polarised debate over EU immigration. The assumption that the UK had become a ‘honeypot nation’ for welfare-seeking EU immigrants was one of the potential reasons that prompted many voters to back Brexit.

But this debate was not unique to the UK. Similar – and equally strong – assumptions about the negative impact of EU immigration on welfare states are found in other EU countries. Fears of ‘welfare magnetism’ are especially prominent in Denmark. The leaders of almost all of the country’s political parties have united in expressing their deep concern about the viability of – or support for – Denmark’s welfare state in light of EU free movement, given that many Danes view their welfare system as being particularly generous and attractive.

With a tax-financed, non-contributory welfare state, Denmark is indeed a crucial case for testing the thesis that EU immigration can create a welfare burden. Denmark represents the purest expression of what remains of the Nordic welfare state. Among EU states, it has the largest share of non-contributory benefits. For most welfare benefits, entitlement does not depend on having contributed to the scheme. And in comparison with other EU member states, benefits tend to be relatively generous.

To illustrate, a Danish study grant for 2017 is approximately 800 euros per month. This is a universal benefit granted to all students regardless of their parents’ income. Additionally, students can take out loans. Families with children that are 18 years old or younger in Denmark are entitled to child benefits. This benefit is also universal and again granted independently of income. The amount paid depends on the age of the child, but is on average about 160 euros per month per child (as of 2017). A Danish social assistance benefit is currently around 1,450 euros per month. Social assistance is a tax-financed minimum subsistence benefit granted to unemployed individuals who do not qualify for higher contribution-dependent unemployment benefits and do not have their own resources to live on. The Danish unemployment benefit is, on the other hand, insurance-based. The amount paid can be up to a maximum of 90% of the member’s previous work income, but no more than a maximum rate of approximately 2,300 euros per month (2017 level).

Thus, the Danish welfare state is generally regarded as being more attractive than the presumed UK ‘honey pot’ and is therefore a more likely case for confirming whether the ‘welfare magnet thesis’ is a genuine concern. Moreover, while the UK government has previously admitted that it does not know the extent to which EU migrants have benefitted from the UK welfare system, we have extensive data on this topic for Denmark.

A unique dataset

In a recent study, we have analysed both the contribution of all EU citizens residing in Denmark to the Danish welfare system, and the consumption of welfare spending by these citizens between 2002 and 2013. The data was compiled from a unique dataset of Danish register data, allowing for a detailed and fairly exhaustive examination of welfare contributions and expenditures. In addition, the time period examined is important as it allowed for an analysis of the welfare impact of EU immigration during 12 years of significant EU change. Perhaps such a period of dramatic EU change will never occur again, given this included the EU enlargements of 2004 and 2007, with ten new Eastern European member states along with Cyprus and Malta joining, changes in EU law regarding residency and cross-border welfare rights, the financial crisis, and the termination of transitional arrangements for the free movement of people from the new member states, which Denmark had in place until 2009.

During this period, the number of EU immigrants increased considerably in many member states, including Denmark. By the end of 2002, around 54,000 citizens from other EU countries lived in Denmark. By the end of 2013, this had grown to 160,000. To assess the fiscal impact of this change, administrative data on all EU citizens’ contributions through taxation, VAT (indirectly calculated) and labour market contributions were compiled and compared with their welfare expenditures in terms of cash benefits and service benefits. The average expenditures for public goods (defence, environment protection, waste management, infrastructure, and so on) were also taken into account in part of the analysis. To avoid overestimating the contribution from EU citizens, we chose to use a conservative calculation of the remittances on VAT payments from EU citizens in their first five years of residence. We were not able to include corporate tax as a contribution. As such, had we chosen a less conservative method, the net contribution may have been significantly higher.

EU citizens as net contributors to the public purse

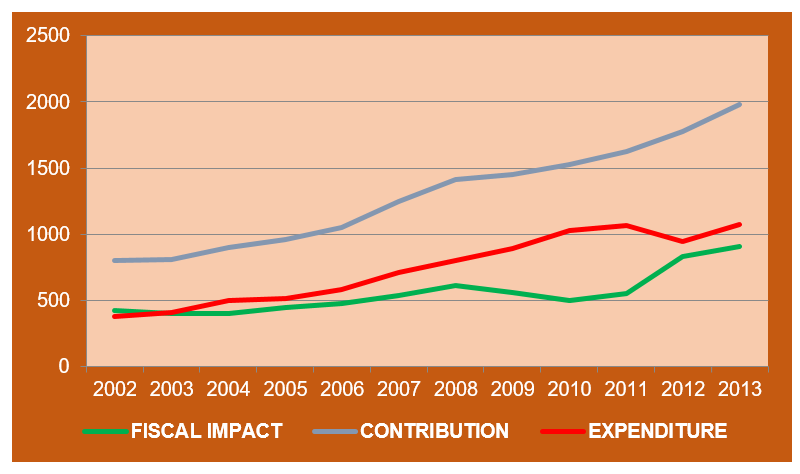

Overall, our findings show that EU citizens have been net contributors in Denmark – both accumulated and on average. Over the entire period, EU immigrants have made a significant positive fiscal contribution to Denmark of 6.63 billion euros. In 2013, the total net contribution of EU citizens to the Danish public purse was about 910 million euros. Furthermore, apart from the years of crisis, 2008–2010, the average fiscal impact remained rather constant at around 6000 euros per year per EU citizen. The positive return of EU immigrants to the welfare state was recently confirmed also for 2014 in a report from the Danish Ministry of Finance. Figure 1 presents EU citizens’ net contribution between 2002 and 2013.

Figure 1: Total fiscal impact of EU citizens per year in Denmark from 2002-2013 (million euros)

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying journal article in European Union Politics.

A few other findings from the study should also be noted. EU citizens are overrepresented in the ‘working age group’ compared to the Danish population as a whole. The overrepresentation is highest for EU citizens from the new member states. Furthermore, EU citizens from the new member states contribute on average less than citizens from the old member states because of a lower average income but, at the same time, they do not use welfare benefits to the same extent.

The overall conclusion from the study is that EU citizens have contributed to financing the Danish welfare state – throughout a period of significant economic and political change. The findings should invite us to rethink the free movement-welfare state nexus. They suggest that the welfare state is much less vulnerable to the impact of free movement than current political discourse would dictate, and in fact the public finances of a state can benefit from EU immigration. Just as important is that the profile of EU citizens does not fit the picture of a ‘welfare tourist’. Instead, EU migrants tend to be relatively young, contribute financially to the system, and take time to claim benefits.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is based on the authors’ recent study in European Union Politics. The study was supported by Norface’s independent research programme, Welfare State Future as part of the project TransJudFare. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen – University of Copenhagen

Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen – University of Copenhagen

Dorte Sindbjerg Martinsen is a Professor in the Department of Political Science at the University of Copenhagen. Her research focuses on EU social policy, its impact at the national level and the interplay between law and politics in the EU. She is the author of ‘An Ever More Powerful Court – the Political Constraints of Legal Integration in the European Union’ (Oxford University Press).

Gabriel Pons Rotger – VIVE – the Danish Social Centre of Applied Social Science

Gabriel Pons Rotger – VIVE – the Danish Social Centre of Applied Social Science

Gabriel Pons Rotger is senior researcher and economist specialized in policy evaluation and social interaction effects analysis with individual data at VIVE – the Danish Social Centre of Applied Social Science. Among other themes, his current research focuses on the fiscal impact of EU citizens in Denmark and the effectiveness of intensive labour market policy.

This article seems to leave out that it wasn’t the right to benefits which British people objected to, it was how benefits could be claimed for children not living in the country.

I can’t imagine many people actually voted on the basis of the sensationalist articles about child benefit being sent abroad that we periodically had to endure from the Express, but even if they did, the claim was that it costs around “£30-50 million” a year. That’s an absolutely tiny figure in comparison to the wider discussion about how much EU immigrants put into the economy.

“The participation of EU citizens …. and their rights to welfare benefits – sat at the heart of a heated, polarised debate over EU immigration. “

There is little evidence that welfare benefits was “at the heart” of the debate.

Overwhelmingly people mentioned the impacts of millions of extra people;

– Housing costs pushed up

– Shortage of school places

– Longer waits for a Doctor

– Overcrowded Transport

etc,

Generally it is accepted that most migrants work hard and “do the right thing”.

What about the data?

“By the end of 2013, this had grown to 160,000.” – the total number of EU citizens in Denmark – ever.

That’s half the migrants the UK has received in one year !

As for the “net benefit” argument ….

Please can the authors tell us the income distribution – and therefore tax take of these 160,000.

It is entirely possible that a wealthy 1/4 pay 3/4 of the taxes.

Put another way ….

– What is the median income?

Is it lower than the arithmetic mean ?

– How much tax would that person pay ?

At a guess … not much ….. but there are probably enough EU lawyers and bankers to pay lots of tax so resulting in a “net positive”.

“Put another way ….

– What is the median income?

Is it lower than the arithmetic mean ?

– How much tax would that person pay ?

At a guess … not much ….. but there are probably enough EU lawyers and bankers to pay lots of tax so resulting in a “net positive”.”

This is pretty half-baked even by your standards. They already explained some of the reasons why EU immigrants are a net benefit: they’re more likely to be of working age (rather than pensioners or children) and they’re less likely to claim benefits (because they’re there to work). This shouldn’t be surprising, the same factors are also present with EU immigrants in the UK.

Burns – you STILL can’t refrain from belittling …. (“pretty half-baked even by your standards”)

I note that you haven’t actually answered the questions I posed of the authors.

The comments re-quoted can all be true – but the “EU immigrants are a net benefit” is misleading.

I really don’t want to sound patronising but ……

Imagine a room with 10 people.

1 earns 1,000,000 p.a.

The other 9 earn around 20,000 p.a.

The average is nearly 120,000 p.a. – so superficially the group is a “net benefit”.

Obviously in the real world incomes are more spread out – but the point remains…..

A few thousand well paid professionals can more than offset many thousands of fruit-pickers ….

….. in terms of tax paid versus direct benefits received.

Where is the “cost” of:

– housing

– school places

– transport

– health

etc, etc ?

I’m not sure why you’ve felt the need to explain the same point again when we all understood it the first time. This article is based on a peer-reviewed study which happens to have produced a conclusion you don’t like. It’s clearly explained in the study why EU immigrants, on average, are a net benefit to Denmark. These factors are almost identical to the reasons why previous studies have found that EU immigrants are a net benefit to the UK: the two major ones, as I said above, are linked to their age (they come here during their working years) and the fact they don’t access benefits as frequently (or that there’s a delay in them doing so).

Your response has been to largely ignore the actual study, toss out the first critique that came to mind, and try to invalidate the results. Your critique in this case is completely inconsequential. To give just two reasons: First, all groups of citizens will have richer individuals contributing a disproportionate level of taxation revenue. You’ve presented this possibility as if it would somehow invalidate the conclusion about the merits of EU immigration, when in reality it’s a situation that will apply to virtually any group in society. Second, we already know that the two major explanatory factors (age and tendency to access benefits) are present across the group of EU immigrants as a whole and that the benefits are therefore not a quirk caused by a few outliers.

Your critique isn’t grounded in evidence, is at odds with the explanatory factors, and would be completely inconsequential even if it were true in the first place. It was pretty much the textbook definition of “half-baked” and fairly typical of the kind of arguments you produce on here: extremely dismissive of anything that doesn’t match your political allegiances, but lacking any genuine substance to back up your views.