The CDU/CSU and the SPD are set to discuss the possibility of renewing their grand coalition in Germany, following the breakdown of negotiations between the CDU/CSU, Greens and the FDP. Rakib Ehsan assesses the dilemma facing the SPD as it considers joining another government. He argues that the party sorely needs a period in opposition to try and resolve internal tensions and win back the support it lost in the recent federal elections, but the obligation to govern and ensure political stability may be difficult to refuse.

The CDU/CSU and the SPD are set to discuss the possibility of renewing their grand coalition in Germany, following the breakdown of negotiations between the CDU/CSU, Greens and the FDP. Rakib Ehsan assesses the dilemma facing the SPD as it considers joining another government. He argues that the party sorely needs a period in opposition to try and resolve internal tensions and win back the support it lost in the recent federal elections, but the obligation to govern and ensure political stability may be difficult to refuse.

The failure to negotiate a coalition following the 2017 German federal elections has produced Angela Merkel’s greatest political crisis as Chancellor. In retrospect, the breakdown of intra-party coalition talks between the conservative CDU/CSU, the left-of-centre environmentalist Greens, and the pro-business FDP, was inevitable. The FDP’s walk-out should have come as no surprise given the party remains relatively sceptical of further European integration, holds a conservative stance on family reunification for Germany’s recent Muslim refugees, and has adopted a gradualist approach to environmental issues like the phasing-out of coal production.

The potential “Jamaica coalition” (named after the corresponding colours of the constituent parties and the Caribbean island’s national flag) is now very much dead in the water. And the disintegration of the talks left Merkel with two options. One was to call fresh elections, which could potentially deliver a similarly complicated balance of power and do little to solve the impasse. The second was to strike a coalition with the Social Democrats (SPD) and establish a new grand coalition. Momentum is now growing behind this second option, but it will be far from straightforward for Merkel to achieve.

The SPD’s predicament

The recent federal election was a particularly bruising experience for the SPD. The party won just 20.5 per cent of the popular vote, fewer than 8 percentage points ahead of the right-wing populist Alternative for Germany (AfD). Losing 40 seats in the process, the Social Democrats now hold only 153 of the 709 seats in the Bundestag. The SPD won just over 9.5 million votes in September’s elections, a drastic decline for a party that secured over 20 million votes under Gerhard Schröder in the 1998 federal election.

The SPD is now a party in crisis – and one riven by internal tensions over economic and cultural issues. The “Seeheimer Kreis” wing of the SPD is relatively market-friendly and pro-business. Favouring labour market flexibility and limited welfare provision, it supports the Agenda 2010 and Hartz IV reforms spearheaded by Schröder under his chancellorship. On the other side of the divide, the “Keynesian traditionalist” faction of the SPD continue to view these reforms as the destruction of the SPD’s democratic socialist identity. This latter grouping desires a more “interventionist” German state and finds ideological common ground with the far-left political party Die Linke.

The party is also fractured along cultural values. The SPD has “cosmopolitans” who embrace the cultural diversity that comes with immigration, and view migration as economically beneficial for Germany’s ageing society. They tend to support a liberal refugee and asylum policy in the name of global obligation and compassion. On the other hand, “preservationists” have grown increasingly uneasy with the pace of social change in Germany. They are sceptical of both the economic and cultural benefits of immigration and, crucially, they favour a stricter refugee and asylum policy, especially towards claimants originating from unstable Muslim-majority societies.

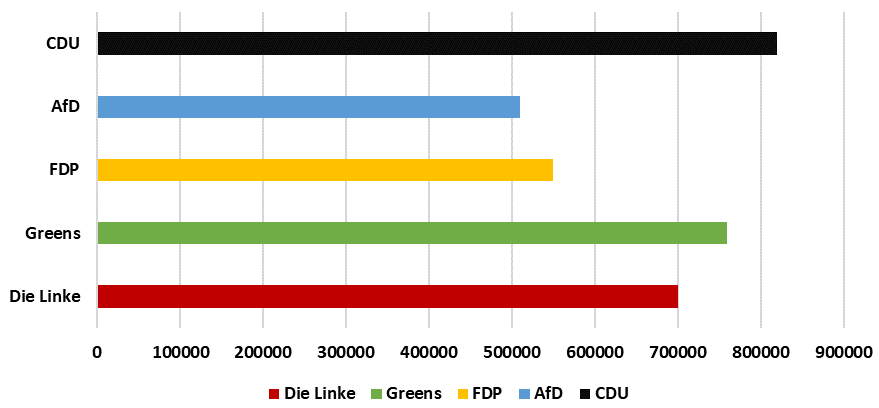

The internal tensions within the SPD tap into the electoral success of the right-wing, anti-establishment AfD, which champions itself as the “defender of the fatherland”. Indeed, the recent federal election saw an estimated 510,000 voters shift their allegiance from the SPD to the AfD, as shown in the figure below.

Figure: Loss of votes from the SPD to other parties in the 2017 federal elections

Source: Infratest dimap for ARD

The SPD is generally viewed as a pro-EU, internationalist, socially liberal party of the German (and European) political establishment. Its current leader, Martin Schulz, served a five-year term as President of the European Parliament from 2012-2017. Unfortunately, this puts the party fundamentally at odds with sections of its traditional “blue-collar” vote. Many are sceptical of EU freedom of movement and its perceived negative effects on their wages and employment. Some are uneasy with the changing ethnic and religious composition of German society. An increasing number view the growing presence of Islam in Germany as both a cultural preservation and domestic security issue.

Liberal views on European integration, migration, refugees, cultural diversity and minority rights are increasingly unpopular among working-class Germans who have traditionally voted for the SPD. The figures suggest a telling number were indeed seduced by the anti-EU, culturally conservative message put forward by the AfD, based on tougher border controls, a stricter refugee policy, cultural assimilation for existing migrants and a critical stance on Islam’s role in German society. Their vote was a rejection of a socially liberal, multicultural Germany – and an electoral middle finger up to the SPD.

Desire for opposition, but obligated to govern

The intra-party tensions within the SPD, coupled with the party’s disastrous electoral performance, leads to an obvious conclusion: that the SPD desperately requires a period in opposition. The party needs to regroup, critically analyse its dire performance in the last election, and decide how to effectively reconcile its internal tensions and reunify.

It also requires a coherent national policy agenda for future electoral success, and a strategy for reengaging with those who have abandoned it for right-wing populism. It can only truly achieve this if it is free from the everyday pressures of governing Germany. Moreover, a new grand coalition risks making the German political establishment more vulnerable to the threat of populism, as it would effectively make the AfD the largest opposition party at the federal level.

The FDP, by withdrawing from coalition talks, chose to walk away from power for the sake of its own party interests. As a party that had just returned to the Bundestag, it may have been fearful of the electoral recriminations that often come for smaller parties when they make policy compromises. But in a country where co-operation and consensus run deep in the postwar democratic culture, the SPD’s obligation to govern and help Merkel deliver political stability may prove difficult to resist. Whether this proves to be in the long-term interest of the party remains to be seen.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Markus Spiske (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

Rakib Ehsan – Royal Holloway, University of London

Rakib Ehsan – Royal Holloway, University of London

Rakib Ehsan is a Doctoral Researcher at Royal Holloway, University of London. His PhD research investigates how ethnic composition of social networks and discriminatory experiences affect social trust, satisfaction with democracy and self-identification among British ethnic minorities.