Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement has a lead in the opinion polls ahead of the Italian general election in March. As Davide Vittori and Margherita de Candia explain, one of the key features of the party’s rise to prominence prior to the 2013 general election was its use of online participation. However, they note that things have changed markedly in the years since, with the party experiencing a decline in the online participation of members, and a growth in its ‘offline’ presence.

Beppe Grillo’s Five Star Movement has a lead in the opinion polls ahead of the Italian general election in March. As Davide Vittori and Margherita de Candia explain, one of the key features of the party’s rise to prominence prior to the 2013 general election was its use of online participation. However, they note that things have changed markedly in the years since, with the party experiencing a decline in the online participation of members, and a growth in its ‘offline’ presence.

When Beppe Grillo launched the Five Star Movement (FSM) back in 2009, few would have bet on its political survival. Eight years have elapsed since then and the FSM now counts 123 representatives in the Italian Parliament (163 originally), 15 in the European Parliament (17 originally), and several regional and local representatives. Polls place the FSM first in terms of public support ahead of the upcoming Italian general election in March.

The innovative use of the internet as a means of mobilisation and participation has been key to its success. In times of growing disenchantment with the established political class (Eurobarometer data are telling in this context), the FSM appeared to many as a breath of fresh air. By opening up new spaces for both online and offline participation, Grillo swiftly appealed to politically inactive citizens. According to a survey conducted in 2013, 27.5 per cent of FSM supporters reported to have abstained from voting in the previous general elections.

Yet data seems to point to a progressive decline in the once very keen online participation of FSM supporters. Last September’s online primaries for the selection of the FSM would-be Prime Minister are revealing in this regard. Despite 150,000 members being entitled to vote (as affirmed by an FSM MP), only 37,442 votes were cast. Member participation in the forthcoming MP primaries is not expected to exceed the previous result. This trend seems at odds with the growing support the FSM gets on the (offline) ground. But what explains this paradox and what can it tell us about the changing nature of the party?

Electoral (offline) growth

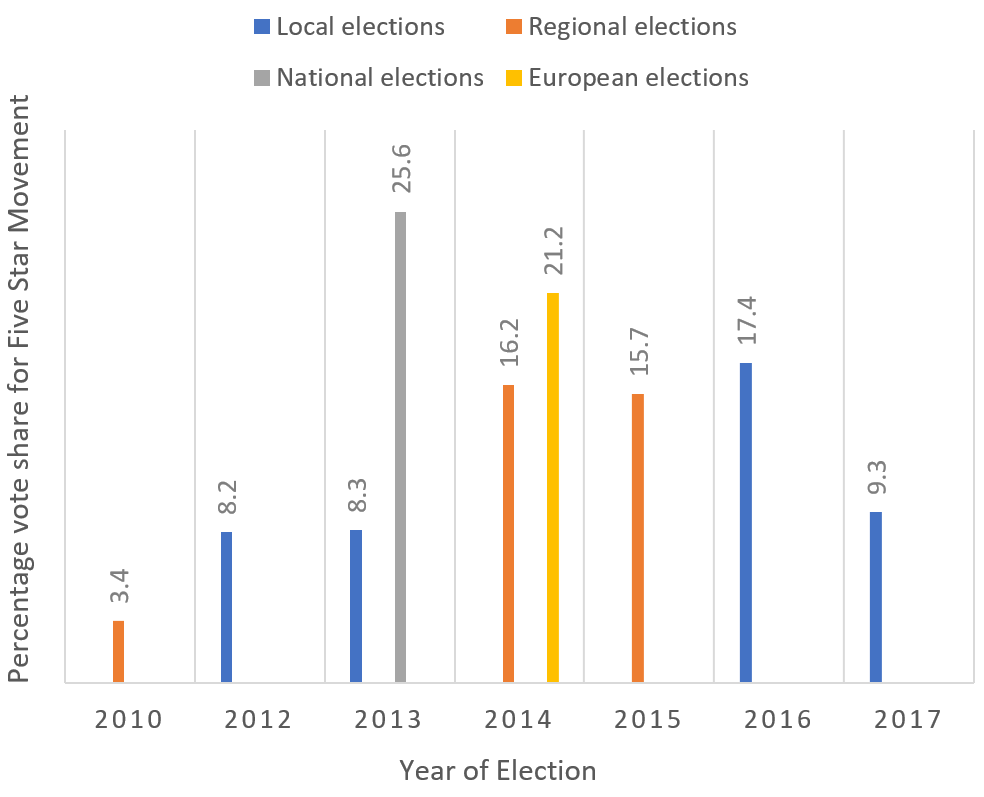

After participating, with modest success, in a few local elections in 2009 under the label Amici di Beppe Grillo, the FSM has increasingly expanded its presence throughout Italy. As Table 1 illustrates, the electoral result in the regional elections in 2010 was encouraging, but remained limited. On that occasion, Grillo’s movement achieved positive results in some affluent and progressive regions, such as Emilia-Romagna (7 per cent) and Piedmont (4.1 per cent), but remained weak in the South.

An impressive growth in support followed the regional elections, as testified by the results of the 2013 general election, where the party received 25.6 per cent of the vote. Even though the 2014 European elections (21.2 per cent) and the 2017 local elections marked a decrease in its share of votes, the FSM is now credited with being the most-voted party in Italy. Moreover, its victories in major cities (2016), such as Rome and Turin, have presented the party as an ‘eligible’ proposition in a second-runoff vote and helped increase its credibility. In the recent Sicilian elections, the Five Star Movement was the most voted party (26.7 per cent) (although the centre-right coalition won the absolute majority with 39.8 per cent of votes).

Figure 1: The Five Star Movement’s vote share by year and level of government

Note: The 2010 regional election result refers to the percentage of list votes obtained in the five regions in which the Five Star Movement participated in the elections; the 2012 local election result refers to the 20 main cities in which the Five Star Movement presented its list; the 2013, 2016, and 2017 local election results refer to vote shares in main cities that contain more than 15,000 inhabitants; and the 2014 and 2015 regional election results refer to the percentage of the list vote received by the Five Star Movement. Source: Compiled by the authors.

External/internal troubles and declining online participation

In parallel with its electoral growth, the Five Star Movement has experienced a series of scandals (notably its problems in Rome) and suffered from infighting. Between 2011 and 2012, several local members in Emilia-Romagna were expelled by Grillo and his co-leader Gianroberto Casaleggio for their alleged violation of internal rules. Since 2013, 9 MPs have been dismissed upon approval via internal referendums, while others have left the party in solidarity with their colleagues (40 MPs in total). Subsequently, the discovery of private contracts between MPs, MEPs and local candidates has raised questions about the control exercised by Grillo and Casaleggio over the FSM and its online resources. The last case in point is the incrimination of several party members in Sicily in 2017. They were accused of having forged the signatures of party supporters for the 2012 mayoral elections in Palermo.

From an electoral standpoint, these problems do not seem to have affected the party. But while it seems reasonable to expect higher involvement from the membership in line with the growing electoral potential of the party, our analysis reveals a different picture. From the outset, members of the Five Star Movement have been involved first-hand in key party decisions through online polls (from consultation on various policy issues to the selection of electoral candidates and the drafting of the political programme). This initially took place on Grillo’s blog, but from 2016 all votes have been cast via the online platform Rousseau.

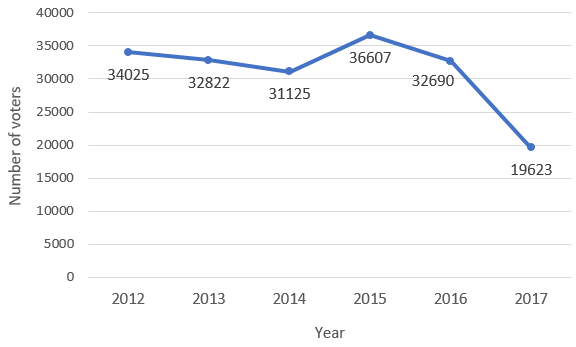

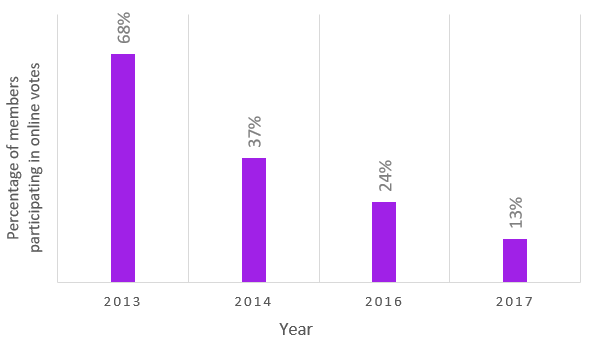

The figures below provide an overview of how online participation by FSM activists has evolved over time. Figure 2 shows the mean total number of voters by year (the average yearly number of members who have participated in online polls), while figure 3 indicates the percentage of voters out of the total number of members entitled to vote.

Figure 2: Mean number of voters in online polls conducted by the Five Star Movement

Note: Authors’ calculations using data from www.beppegrillo.it.

Figure 3: Percentage of total members participating in online votes

Note: Authors’ calculations using data from www.beppegrillo.it. Data on the official number of total members were not available for all votes: in cases where these are missing the average for the same year is used; no data were available for 2015.

These descending trends and the low participation rate seem at odds with the initial claim that the Five Star Movement “has direct democracy in its DNA”. Hence, the question arises as to whether the party has become more interested in electoral consensus rather than citizens’ active participation. The former is not an unreasonable process in itself, but it shows that in less than four years the party has ‘normalised’ its participatory impetus.

Electoral consensus as the new mantra?

The Five Star Movement’s growth has upset the Italian political system in several different ways. Notably, it has transformed the two-decades old multi-party bipolarism into a tripolar competition, in which one pole (the FSM) rejects any collaboration with the other parties. Nevertheless, the party was established to pursue far more ambitious aims: no less than transforming the way politics is done. Web-based direct-democracy was meant to substitute traditional patterns of political participation, tackle the malaises of representative democracy, and get rid of the ‘old’ parties.

The attempt to disintermediate the relationship between the ‘represented’ and the ‘representatives’ is nothing new; still, the Five Star Movement represents the electorally most successful web-based experiment. Leaving aside any criticism of the top-down functioning of the party organisation, which allegedly uses direct-democracy to legitimise ready-made decisions, the figures above illustrate that the membership’s participation within the Five Star Movement is not only relatively modest, but also dropping.

Grillo once maintained that “old politics is on the wane”. Yet if online participation rates continue to decline and the focus of the party leadership and public officials is all on electoral consensus – as the recent (radical) change in the internal rules seems to suggest – the FSM may well risk becoming part of the political establishment they wanted to get rid of.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Matteo (CC BY-SA 3.0)

_________________________________

Davide Vittori – LUISS University

Davide Vittori – LUISS University

Davide Vittori is a PhD Student at LUISS University. His main research interests are party politics, movement parties, party organisation and populism. His last publication is Podemos and the Five Stars Movement: Divergent trajectories in a similar crisis (Constellations).

Margherita de Candia – King’s College London

Margherita de Candia – King’s College London

Margherita de Candia is a PhD candidate at King’s College London working on the interaction between national parties and the European Parliament. She has a keen interest in British and Italian politics.