Pippa Norris explains how generation gaps divide the British electorate and mainstream parties. She writes that while the EU referendum was a prime example of how these divisions play out in the UK, the changing nature of electoral cleavages raises important questions about politics and party competition in western democracies more generally.

Pippa Norris explains how generation gaps divide the British electorate and mainstream parties. She writes that while the EU referendum was a prime example of how these divisions play out in the UK, the changing nature of electoral cleavages raises important questions about politics and party competition in western democracies more generally.

The Brexit decision shocked Britain’s image of itself, and sent reverberations around the world. Until recently, Westminster shared a broad consensus about the value of the liberal international order abroad and liberal democratic governance at home. The accord reflected a cosmopolitan vision, convinced of the benefits of access to global markets, open border, and international cooperation. In Europe, the ‘permissive consensus’ allowed Brussels technocrats to pursue a common vision of deepening and enlarging the EU, without giving a direct voice to the European public on the matter – even though polls suggest that this goal was increasingly rejected by many of its citizens.

At home, as well, the major UK parties differed on many economic and social policies, and the Conservatives have obviously been deeply divided on Europe ever since Thatcher. Nevertheless, beyond policy debates, during the 1990s British politicians on both sides of the aisle seemed to share broad agreement about the underlying rules of the game, tolerant respect for robust pluralistic debate at Westminster, and support for liberal democratic norms. This includes the values of liberal freedoms, social tolerance, and respect for diversity, the protection of minority rights, and the rejection of the forces of authoritarianism, racism and xenophobia. Mainstream parties agreed to quarantine the BNP, the National Front, and other fringe alt-right white nationalists.

In recent years, however, the outcome of the Brexit referendum and its dithering aftermath, the bitterly divisive splits within both the major parties, and polarizing battles over anti-Semitism in the Labour party and Islamophobia in the Tories, have shaken faith in the traditional tolerance of British society, raised challenges to the liberal consensus concerning the principles of democratic governance, and threatened the stability and unity of the UK.

The well-known story behind Britain’s momentous decision to seek a divorce from the European Union, after more than four decades, and the historical role of UKIP in this process, rests ultimately on ‘supply-side’ factors in Westminster politics – including the critical impact of contingent historical events and key blunders by spectacularly inept and short-sighted political leaders.

On the ‘demand side’ of the equation, once the referendum was triggered, several factors help to explain the main drivers of public opinion and voting behavior determining the outcome of the 2016 referendum – as well as the ups and downs of UKIP’s electoral support during the 2015 and 2017 general elections. Work by Harold D. Clarke et al. argues that Euroscepticism was fueled by anxieties about government management of immigration and, to a lesser extent, the economy and NHS. But a broader comparative perspective suggests that Brexit is part of the phenomenon of authoritarian-populism which has been sweeping across the globe, so it needs a more general explanation than one based on British party politics alone.

Beyond specific policy issues, several authors have sought to describe the emergence of a long-term cultural cleavage. For example, David Goodhart depicts Britain as split between the ‘Anywheres’, the degree-educated, geographically mobile professionals who embrace new people and experiences, and define themselves by their achievements; and the ‘Somewheres’, with a fixed identities rooted in their hometown community, unsettled by rapid change, particularly the influx of migrants, the growth of multiethnic cities, and more fluid gender identities.

Many have referred loosely to the ‘Left-behinds’ as an economic category referring to the losers from global trade. These ideas partially capture some of the tensions observed in the UK and can be applied elsewhere, such as the familiar divisions observed between the God and Guns values of heartland Trump America and the Climate Change and Diversity values of coastal Obama-nostalgic elites, or between voting support for Macron in urbane Paris and Le Pen in Ardennes, Alsace and Marseilles.

But observing the contrasts doesn’t help to explain the contemporary reemergence of this classic center-periphery geographic division – and thus why some people have become increasingly more reluctant to embrace social change than others. Impressionistic notions such the distinction between ‘Anywheres’ and ‘Somewheres’, or ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ from global markets, are also fuzzy concepts to measure. The distinction can also sound patronizing, as though the Left-behinds are deeply irrational and they just need to get with the culture.

In a new book on Cultural Backlash forthcoming in the fall, we argue that support for Authoritarian-Populist parties and leaders in Europe and America, and the bitter polarization over Brexit in the UK electorate, reflects culture wars over fundamental social values dividing young and old in many Western societies. There is widespread evidence from the British Attitudes Survey that British society continues to move in a socially-liberal direction, with younger and college-educated people being far more tolerant than older and less-educated groups on same-sex marriage, LGBTQ rights, abortion, euthanasia, pornography, and pre-marital sex.

Millennials are also far more likely to have voted Remain, while a study of young people in Britain concluded that many are concerned about the negative impact of Brexit on multi-ethnic communities – and they expressed concern about rising intolerance, discrimination, racism and the decline of Britain’s multicultural image. They were also resentful that the decision to leave the EU was made by the older generation and concerned that Brexit would limit their opportunities to live and work in Europe.

Meanwhile, the Interwar generation supported Leave, and UKIP, because they tend to endorse a broader range of socially-conservative and authoritarian values associated with nationalism, Euroscepticism, and immigration. The generation gap in Europe and America is linked with cultural cleavages around these issues. As the old Left-Right divisions of social class identities have faded in Britain, an emerging cultural war deeply divides voters and parties around values of national sovereignty versus cooperation among EU member states; respect for traditional families and marriage versus support for gender equality and feminism, tolerance of diverse lifestyles and gender fluid identities; the importance of protecting manufacturing jobs versus environmental protection and climate change; and restrictions on immigration and closed borders versus openness towards refugees, migrants, and foreigners.In the long-term, the silent revolution continues to move the Western societies gradually in a more liberal direction. In the short-term, however, older generations are far more likely to vote than the young – and the authoritarian reaction against progressive values has mobilized to become significant force in politics.

Our book accounts for the rise of Authoritarian-Populists in many Western societies by emphasizing the long-term consequences of the Silent Revolution in cultural values. This started to become evident with post-materialist value change among the younger and college educated generation who grew up in affluent post-industrial societies during the 1960s and 1970s. The proportion of more socially-conservative older cohorts holding traditional values towards core identity issues, such as those surrounding the values of religion, family, and nation, has gradually faded away over the years and younger generations with more socially liberal views gradually took their place in the population.

The proportion of Interwar and Baby Boomers in Western societies has gradually declined, losing hegemonic status and cultural power – although they usually remain a bare majority of active voters and thus their preferences continue to be over-reflected in representative bodies. At a certain point, a tipping point occurs in society, as the proportion of those holding traditional values becomes the new minority in the population. This experience, we theorize, triggers an authoritarian reflex among the older and less educated sectors most resistant to cultural change, who seek strong leaders to defend socially-conservative values, blaming liberal elites like Westminster politicians, the media, academic experts, Eurocrats and the establishment in general, as well as out-groups like immigrants and foreigners for lack of respect for traditional values.

This account can be applied to help explain the outbreak of cultural wars over Brexit and its dispiriting aftermath. If so, then the division between the Leave and Remain camps should be found to revolve around the cultural cleavage between authoritarian and libertarian values, especially where Leave is endorsed by older generations who feel threatened by the rapid pace of cultural change and the loss of respect for traditional ways of life. The threat to socially-conservative values is expected to have triggered an authoritarian reflex among these groups – emphasizing the importance of maintaining collective security by enforcing strict conformity with traditional mores within the tribe, a united front against outsiders, and loyalty towards tribal leaders.

This orientation is reinforced by populist leadership rhetoric reasserting the legitimate voice of ‘Us’ through claiming ‘power to the people’, denigrating the authority of Westminster politicians at home and, of course, Eurocrats and EU institutions abroad. The cultural backlash thesis argues that a tipping point in the long-term process of cultural change has been mobilized and reinforced by authoritarian-populist leaders, whether opportunistically motivated to advance their personal ambitions (Boris Johnson?) or whether they share similar values (Donald Trump?) or a bit of both. These developments reflect a new cultural cleavage in party competition and in the electorate, emerging not just in Britain, but also in many other Western societies.

What evidence supports this thesis? Cultural Backlash provides a broad cross-national comparison across Western societies. For a snapshot on some of the evidence in the case of the UK, we can draw on the British Election Study (BES) panel survey of 31,196 respondents conducted by YouGov over 13 waves from February 2014 until after the June 2017 general election.

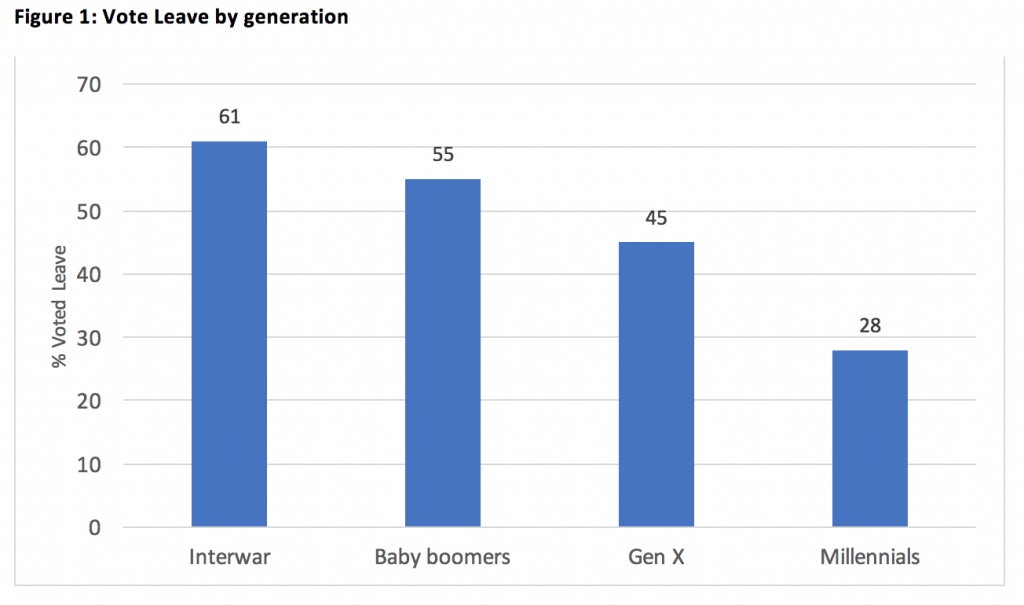

The survey evidence is most clear-cut and consistent across numerous polls for the sizeable generation gaps observed in voting for Brexit and in recent general elections in the UK. Figure 1 illustrates the contrasts in the BES, demonstrating that roughly twice as many of the Interwar generation voted Leave compared with the Millennials.

Note: “In the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how did you vote?”. Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13. Wave 9 post-Brexit (24 June to 6 July 2016)

Note: “In the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how did you vote?”. Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13. Wave 9 post-Brexit (24 June to 6 July 2016)

What explains the generational gaps over leaving the EU and support for UKIP? We suggest that the Millennials and Gen X disliked the Leave camp and UKIP’s appeals to English nationalism and white nativism, racial and ethnic intolerance, and social conservatism. They were more strongly attracted to other parties with a cosmopolitan outlook and socially-liberal policies on cultural and moral issues, exemplified by Labour’s manifesto pledges to support LGBTQ equality, women’s rights, anti-racism, protecting animal welfare, lowering the voting age to 16, supporting international development, and building sustainable environments.

Figure 2: Authoritarian values predict voting for Leave and UKIP

Note: Authoritarian values in Britain can be gauged using a BES 100-point standardized scale calculated from the following agree/disagree items: “(1) Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values; (2) People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences; (3) For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence; (4) Schools should teach children to obey authority; (5) The law should always be obeyed, even if a particular law is wrong; (6) Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards.”

Note: Authoritarian values in Britain can be gauged using a BES 100-point standardized scale calculated from the following agree/disagree items: “(1) Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values; (2) People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences; (3) For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence; (4) Schools should teach children to obey authority; (5) The law should always be obeyed, even if a particular law is wrong; (6) Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards.”

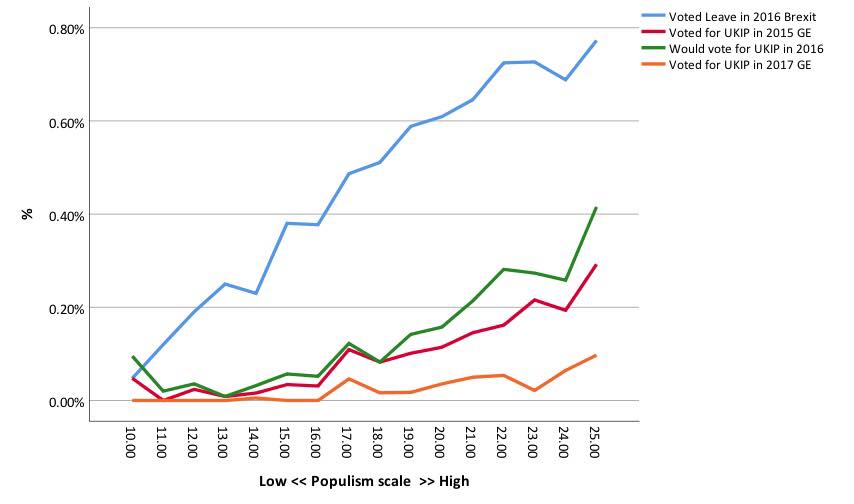

Figure 3: Populist values predict voting for Leave and UKIP

Note: Populism can be measured in from the BES using a similar 100-point standardized scale constructed from the following agree/disagree items: “1) The politicians in the UK Parliament need to follow the will of the people; 2) The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions; 3) I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician; 4) Elected officials talk too much and take too little action; 5) What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles.” Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13.

Note: Populism can be measured in from the BES using a similar 100-point standardized scale constructed from the following agree/disagree items: “1) The politicians in the UK Parliament need to follow the will of the people; 2) The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions; 3) I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician; 4) Elected officials talk too much and take too little action; 5) What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles.” Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13.

To reduce the risk of attitudinal conditioning by prior party voting preferences, authoritarian values were measured in waves conducted months before people went to the polls, and they are designed to tap into a broad sense of the value of social conformity and obedience towards authority, without asking directly about policy issues such as Euroscepticism or anti-immigrant attitudes.

After controlling for the standard socio-economic and demographic variables, the results show that support for both Authoritarian and Populist values strongly predicted Leave voting. As Figure 2 illustrates, authoritarian-libertarian values strongly predict the Leave vote in Brexit and support for UKIP. Similarly disparities can be observed among those scoring highest in the populism scale. Moreover these patterns predict not only who voted Leave in the EU referendum, but also support for UKIP in the 2015 and 2017 general elections. The data confirms that authoritarian and populist values were strongly linked with generational gaps and with voting behavior in Brexit, as expected.

Therefore, the evidence suggests that generation gaps revolving around cultural issues deeply divide the electorate and factions within mainstream parties as well. The Leave vote mobilized the older generation by appealing to nationalistic and nativist identities, achieving a bare majority favoring divorce from the EU, while Gen X and the Millennials were more pro-EU – but also far less likely to get to the polls. If a second referendum were to be held today, the generation gap in turnout is likely to prove critical for the outcome. This development raises important challenges about the changing nature of electoral cleavages and party competition in Britain and elsewhere.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article is drawn from Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart 2018 (forthcoming). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism. NY: Cambridge University Press and originally appeared at our sister site, British Politics and Policy. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain)

_________________________________

Pippa Norris – Harvard University

Pippa Norris – Harvard University

Pippa Norris is the McGuire Lecturer in comparative politics at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, the ARC Laureate fellow and Professor of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, and she is founding director of the Electoral Integrity Project.