Pippa Norris explains how generation gaps divide the electorate and mainstream parties. She writes that, while the EU referendum is a prime example of how these divisions play out in the UK, the changing nature of electoral cleavages raises important questions about politics and party competition in Western democracies more generally.

Pippa Norris explains how generation gaps divide the electorate and mainstream parties. She writes that, while the EU referendum is a prime example of how these divisions play out in the UK, the changing nature of electoral cleavages raises important questions about politics and party competition in Western democracies more generally.

The Brexit decision shocked Britain’s image of itself, and sent reverberations around the world. Until recently, Westminster shared a broad consensus about the value of the liberal international order abroad and liberal democratic governance at home. The accord reflected a cosmopolitan vision, convinced of the benefits of access to global markets, open border, and international cooperation. In Europe, the ‘permissive consensus’ allowed Brussels technocrats to pursue a common vision of deepening and enlarging the EU, without giving a direct voice to the European public on the matter – even though polls suggest that this goal was increasingly rejected by many of its citizens.

At home, as well, the major UK parties differed on many economic and social policies, and the Conservatives have obviously been deeply divided on Europe ever since Thatcher. Nevertheless, beyond policy debates, during the 1990s British politicians on both sides of the aisle seemed to share broad agreement about the underlying rules of the game, tolerant respect for robust pluralistic debate at Westminster, and support for liberal democratic norms. This includes the values of liberal freedoms, social tolerance, and respect for diversity, the protection of minority rights, and the rejection of the forces of authoritarianism, racism and xenophobia. Mainstream parties agreed to quarantine the BNP, the National Front, and other fringe alt-right white nationalists.

In recent years, however, the outcome of the Brexit referendum and its dithering aftermath, the bitterly divisive splits within both the major parties, and polarizing battles over anti-Semitism in the Labour party and Islamophobia in the Tories, have shaken faith in the traditional tolerance of British society, raised challenges to the liberal consensus concerning the principles of democratic governance, and threatened the stability and unity of the UK.

The well-known story behind Britain’s momentous decision to seek a divorce from the European Union, after more than four decades, and the historical role of UKIP in this process, rests ultimately on ‘supply-side’ factors in Westminster politics – including the critical impact of contingent historical events and key blunders by spectacularly inept and short-sighted political leaders.

On the ‘demand side’ of the equation, once the referendum was triggered, several factors help to explain the main drivers of public opinion and voting behavior determining the outcome of the 2016 referendum – as well as the ups and downs of UKIP’s electoral support during the 2015 and 2017 general elections. Work by Harold D. Clarke et al. argues that Euroscepticism was fueled by anxieties about government management of immigration and, to a lesser extent, the economy and NHS. But a broader comparative perspective suggests that Brexit is part of the phenomenon of authoritarian-populism which has been sweeping across the globe, so it needs a more general explanation than one based on British party politics alone.

Beyond specific policy issues, several authors have sought to describe the emergence of a long-term cultural cleavage. For example, David Goodhart depicts Britain as split between the ‘Anywheres’, the degree-educated, geographically mobile professionals who embrace new people and experiences, and define themselves by their achievements; and the ‘Somewheres’, with a fixed identities rooted in their hometown community, unsettled by rapid change, particularly the influx of migrants, the growth of multiethnic cities, and more fluid gender identities.

Many have referred loosely to the ‘Left-behinds’ as an economic category referring to the losers from global trade. These ideas partially capture some of the tensions observed in the UK and can be applied elsewhere, such as the familiar divisions observed between the God and Guns values of heartland Trump America and the Climate Change and Diversity values of coastal Obama-nostalgic elites, or between voting support for Macron in urbane Paris and Le Pen in Ardennes, Alsace and Marseilles.

But observing the contrasts doesn’t help to explain the contemporary reemergence of this classic center-periphery geographic division – and thus why some people have become increasingly more reluctant to embrace social change than others. Impressionistic notions such the distinction between ‘Anywheres’ and ‘Somewheres’, or ‘winners’ and ‘losers’ from global markets, are also fuzzy concepts to measure. The distinction can also sound patronizing, as though the Left-behinds are deeply irrational and they just need to get with the culture.

In a new book on Cultural Backlash forthcoming in the fall, we argue that support for Authoritarian-Populist parties and leaders in Europe and America, and the bitter polarization over Brexit in the UK electorate, reflects culture wars over fundamental social values dividing young and old in many Western societies. There is widespread evidence from the British Attitudes Survey that British society continues to move in a socially-liberal direction, with younger and college-educated people being far more tolerant than older and less-educated groups on same-sex marriage, LGBTQ rights, abortion, euthanasia, pornography, and pre-marital sex.

Millennials are also far more likely to have voted Remain, while a study of young people in Britain concluded that many are concerned about the negative impact of Brexit on multi-ethnic communities – and they expressed concern about rising intolerance, discrimination, racism and the decline of Britain’s multicultural image. They were also resentful that the decision to leave the EU was made by the older generation and concerned that Brexit would limit their opportunities to live and work in Europe.

Meanwhile, the Interwar generation supported Leave, and UKIP, because they tend to endorse a broader range of socially-conservative and authoritarian values associated with nationalism, Euroscepticism, and immigration. The generation gap in Europe and America is linked with cultural cleavages around these issues. As the old Left-Right divisions of social class identities have faded in Britain, an emerging cultural war deeply divides voters and parties around values of national sovereignty versus cooperation among EU member states; respect for traditional families and marriage versus support for gender equality and feminism, tolerance of diverse lifestyles and gender fluid identities; the importance of protecting manufacturing jobs versus environmental protection and climate change; and restrictions on immigration and closed borders versus openness towards refugees, migrants, and foreigners.In the long-term, the silent revolution continues to move the Western societies gradually in a more liberal direction. In the short-term, however, older generations are far more likely to vote than the young – and the authoritarian reaction against progressive values has mobilized to become significant force in politics.

Our book accounts for the rise of Authoritarian-Populists in many Western societies by emphasizing the long-term consequences of the Silent Revolution in cultural values. This started to become evident with post-materialist value change among the younger and college educated generation who grew up in affluent post-industrial societies during the 1960s and 1970s. The proportion of more socially-conservative older cohorts holding traditional values towards core identity issues, such as those surrounding the values of religion, family, and nation, has gradually faded away over the years and younger generations with more socially liberal views gradually took their place in the population.

The proportion of Interwar and Baby Boomers in Western societies has gradually declined, losing hegemonic status and cultural power – although they usually remain a bare majority of active voters and thus their preferences continue to be over-reflected in representative bodies. At a certain point, a tipping point occurs in society, as the proportion of those holding traditional values becomes the new minority in the population. This experience, we theorize, triggers an authoritarian reflex among the older and less educated sectors most resistant to cultural change, who seek strong leaders to defend socially-conservative values, blaming liberal elites like Westminster politicians, the media, academic experts, Eurocrats and the establishment in general, as well as out-groups like immigrants and foreigners for lack of respect for traditional values.

This account can be applied to help explain the outbreak of cultural wars over Brexit and its dispiriting aftermath. If so, then the division between the Leave and Remain camps should be found to revolve around the cultural cleavage between authoritarian and libertarian values, especially where Leave is endorsed by older generations who feel threatened by the rapid pace of cultural change and the loss of respect for traditional ways of life. The threat to socially-conservative values is expected to have triggered an authoritarian reflex among these groups – emphasizing the importance of maintaining collective security by enforcing strict conformity with traditional mores within the tribe, a united front against outsiders, and loyalty towards tribal leaders.

This orientation is reinforced by populist leadership rhetoric reasserting the legitimate voice of ‘Us’ through claiming ‘power to the people’, denigrating the authority of Westminster politicians at home and, of course, Eurocrats and EU institutions abroad. The cultural backlash thesis argues that a tipping point in the long-term process of cultural change has been mobilized and reinforced by authoritarian-populist leaders, whether opportunistically motivated to advance their personal ambitions (Boris Johnson?) or whether they share similar values (Donald Trump?) or a bit of both. These developments reflect a new cultural cleavage in party competition and in the electorate, emerging not just in Britain, but also in many other Western societies.

What evidence supports this thesis? Cultural Backlash provides a broad cross-national comparison across Western societies. For a snapshot on some of the evidence in the case of the UK, we can draw on the British Election Study (BES) panel survey of 31,196 respondents conducted by YouGov over 13 waves from February 2014 until after the June 2017 general election.

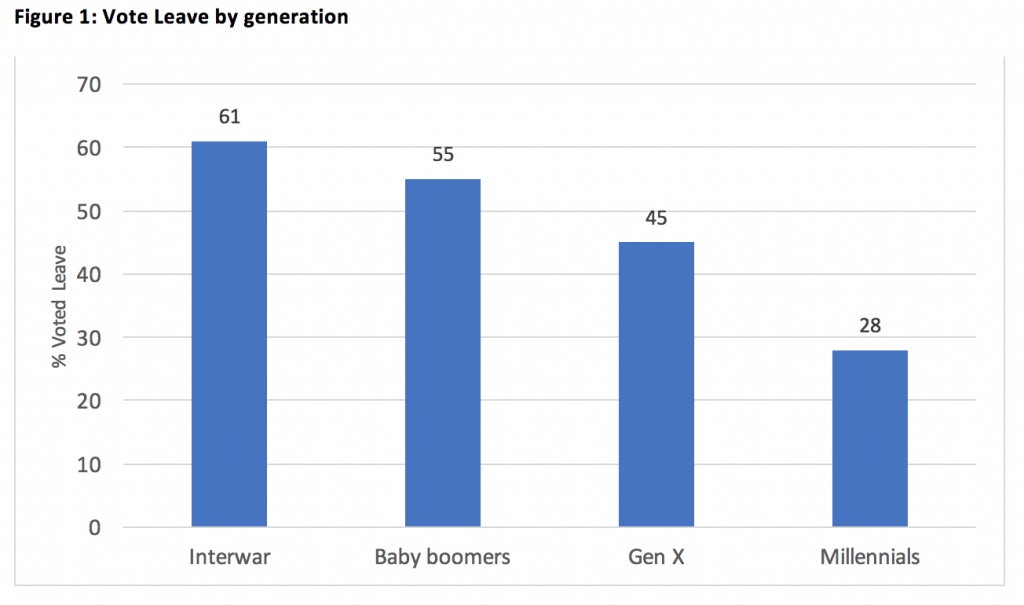

The survey evidence is most clear-cut and consistent across numerous polls for the sizeable generation gaps observed in voting for Brexit and in recent general elections in the UK. Figure 1 illustrates the contrasts in the BES, demonstrating that roughly twice as many of the Interwar generation voted Leave compared with the Millennials.

Note: “In the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how did you vote?”. Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13. Wave 9 post-Brexit (24 June to 6 July 2016)

Note: “In the referendum on Britain’s membership of the European Union, how did you vote?”. Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13. Wave 9 post-Brexit (24 June to 6 July 2016)

What explains the generational gaps over leaving the EU and support for UKIP? We suggest that the Millennials and Gen X disliked the Leave camp and UKIP’s appeals to English nationalism and white nativism, racial and ethnic intolerance, and social conservatism. They were more strongly attracted to other parties with a cosmopolitan outlook and socially-liberal policies on cultural and moral issues, exemplified by Labour’s manifesto pledges to support LGBTQ equality, women’s rights, anti-racism, protecting animal welfare, lowering the voting age to 16, supporting international development, and building sustainable environments.

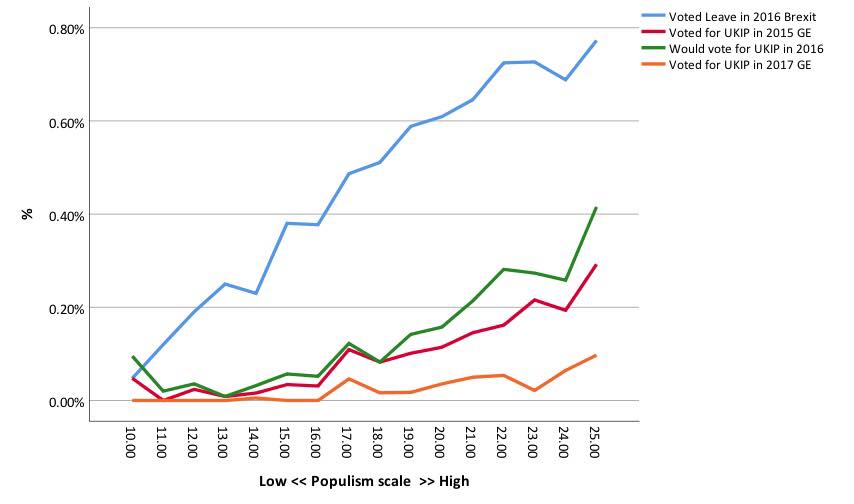

Figure 2: Authoritarian values predict voting for Leave and UKIP

Note: Authoritarian values in Britain can be gauged using a BES 100-point standardized scale calculated from the following agree/disagree items: “(1) Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values; (2) People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences; (3) For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence; (4) Schools should teach children to obey authority; (5) The law should always be obeyed, even if a particular law is wrong; (6) Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards.”

Note: Authoritarian values in Britain can be gauged using a BES 100-point standardized scale calculated from the following agree/disagree items: “(1) Young people today don’t have enough respect for traditional British values; (2) People who break the law should be given stiffer sentences; (3) For some crimes, the death penalty is the most appropriate sentence; (4) Schools should teach children to obey authority; (5) The law should always be obeyed, even if a particular law is wrong; (6) Censorship of films and magazines is necessary to uphold moral standards.”

Figure 3: Populist values predict voting for Leave and UKIP

Note: Populism can be measured in from the BES using a similar 100-point standardized scale constructed from the following agree/disagree items: “1) The politicians in the UK Parliament need to follow the will of the people; 2) The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions; 3) I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician; 4) Elected officials talk too much and take too little action; 5) What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles.” Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13.

Note: Populism can be measured in from the BES using a similar 100-point standardized scale constructed from the following agree/disagree items: “1) The politicians in the UK Parliament need to follow the will of the people; 2) The people, and not politicians, should make our most important policy decisions; 3) I would rather be represented by a citizen than by a specialized politician; 4) Elected officials talk too much and take too little action; 5) What people call “compromise” in politics is really just selling out on one’s principles.” Source: British Election Study Internet Panel Waves 1-13.

To reduce the risk of attitudinal conditioning by prior party voting preferences, authoritarian values were measured in waves conducted months before people went to the polls, and they are designed to tap into a broad sense of the value of social conformity and obedience towards authority, without asking directly about policy issues such as Euroscepticism or anti-immigrant attitudes.

After controlling for the standard socio-economic and demographic variables, the results show that support for both Authoritarian and Populist values strongly predicted Leave voting. As Figure 2 illustrates, authoritarian-libertarian values strongly predict the Leave vote in Brexit and support for UKIP. Similarly disparities can be observed among those scoring highest in the populism scale. Moreover these patterns predict not only who voted Leave in the EU referendum, but also support for UKIP in the 2015 and 2017 general elections. The data confirms that authoritarian and populist values were strongly linked with generational gaps and with voting behavior in Brexit, as expected.

Therefore, the evidence suggests that generation gaps revolving around cultural issues deeply divide the electorate and factions within mainstream parties as well. The Leave vote mobilized the older generation by appealing to nationalistic and nativist identities, achieving a bare majority favoring divorce from the EU, while Gen X and the Millennials were more pro-EU – but also far less likely to get to the polls. If a second referendum were to be held today, the generation gap in turnout is likely to prove critical for the outcome. This development raises important challenges about the changing nature of electoral cleavages and party competition in Britain and elsewhere.

__________

Note: the above is drawn from Pippa Norris and Ronald Inglehart 2018 (forthcoming). Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit and Authoritarian Populism. NY: Cambridge University Press.

Pippa Norris is the McGuire Lecturer in comparative politics at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, the ARC Laureate fellow and Professor of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, and she is founding director of the Electoral Integrity Project.

Pippa Norris is the McGuire Lecturer in comparative politics at Harvard’s Kennedy School of Government, the ARC Laureate fellow and Professor of Government and International Relations at the University of Sydney, and she is founding director of the Electoral Integrity Project.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

Hi Pippa

Aren’t there always significant value differences between the young and old? What about the 60s when maybe the differences were seen as even more extreme. Have you shown that the cleavage is even deeper now?

One narrative you don’t seem to consider is that the credibility of the neo-liberal concensus in place since the 70s has been fundamentally undermined by the Crash and the response of Governments to make the broad populace ‘pay’ for the impacts something they never saw coming while leaving the elite relatively untouched. This is not about people being ‘left behind’ but I think about those marginalised by a system and told they are losers, getting bolder when the emperor turns out to have no clothes.

What are your views on that quite widespread narrative?

regards

Henry

I look forward to reading Norris’ book when it comes out. Explaining the Leave vote in terms of cultural values is likely to be more illuminating than in terms of reaction against austerity policies as per Fetzer’s recent analysis (https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/politicsandpolicy/did-austerity-cause-brexit/; or at least, he tried to explain 10% of the Leave vote attributable to reaction against austerity policies). Her work brings a new angle by looking at the pan-European picture. The EU referendum brought out a dimension of politics that cuts across the traditional Left-Right divide, hence it can be difficult to disentangle the causes over time when looking at only one country. Hence a pan-European picture helps.

However, I would question some of Norris’ presuppositions.

While there are “polarizing battles” battles over anti-Semitism in the Labour party (and galvanised condemnation from Jewish leaders and Jewish rallies), it does not appear there are comparable battles over Islamophobia in the Tories. Boris Johnson’s one-off newspaper column containing 2 provocative metaphors – “letterbox” and “robbers” – and subsequent backlash hardly amount to a battle – his critics probably target him because of his potential threat to the Remain camp in the party.

It is not clear to me why Brexit, splits within the two major parties, anti-Semitism in Labour party and Islamophobia in Tories threatened the “unity of the UK”, which I take to refer to risk of Scottish independence and (more remotely) Northern Irish independence. The risk of the former was present before the referendum, as brought out the 2014 Scottish referendum. Somewhat unexpectedly from opinion polls since 2016 and major loss of SNP seats to the Tories at the 2017 GE, it appears Brexit diminished, not increased, risk of Scottish independence. Political opinion among the electorate has always been split along multiple dimensions – this is normal in a democracy, so I don’t see why the current situation will threaten unity of the UK.

Norris suggests on a broader comparative perspective, Brexit is part of the phenomenon of “authoritarian-populism” sweeping the globe. Many commentators and politicians refer to Brexit as a manifestation of populism, in large party because all the major UK parties except UKIP campaigned for Remain, trade unions, businesses (e.g. as represented by CBI), Bank of England, international economic organisations all warned against a Leave vote, yet the electorate snubbed the “establishment”. However, it is not clear to me how Brexit is a manifestation of authoritarianism – there were not and are not any authoritarian leader leading Brexit (maybe Boris Johnson is a populist, but hardly anyone describes him as an authoritarian). The Leave vote campaigned on slogans of independence, and “taking back control” over money, borders, laws. It is not clear how these motifs amount to authoritarianism.

Brexit attitudes are split along generational lines, as shown by many studies. It will be interesting to see what evidence Norris produces to show that support for authoritarian-populism reflects a generational divide in other European countries (e.g. National Front in France, AfD in Germany, FPO in Austria, Fidesz under Prime Minister Orban in Hungary in recent years and Jobbik party, Golden Dawn in Greece, Freedom Party in Netherlands).

Norris probably is right that in the past decades Western societies have steadily moved in a more socially liberal direction. But one should note that each generation of young people in many developed countries across the world and over the past decades have always been more socially liberal than the older generations. The baby boomers in their youth probably were quite socially radical relative to their parents and grandparents. Now, in their old age, they found themselves on the socially conservative end of the spectrum. It seems as people age, many become more socially and politically conservative and resistant to cultural change.

There is a lot of talk about high correlation between educational level and support for Brexit. But off top of my head, when other variables are controlled for in multivariate studies, educational level is not major explanatory variable to account for the Leave vote by UK districts or by individual vote. When the current older generation were in their youth, only a small percentage went to university and post-16 education was optional, now nearly half of school leavers go onto higher education and education is compulsory up to 18yrs. So I am not sure educational level per se is as influential as claimed in shaping attitude to cultural change. It could be that people with high levels of education tend to get good jobs while those with less education are more vulnerable to downsides of globalisation.

UKIP appealed to English nationalism. But it is a controversial claim to say UKIP appealed to “white nativism”. In referring to the Labour Party and the Labour manifesto as exemplar of cosmopolitan outlook and socially-liberal policies (defender of equality, rights, anti-racism, animal welfare, environmentalism), it is clear where Norris’ political sympathies lie. But it is practising double-standards to compare a party (Labour) based on its manifesto document – which invariably paints itself in a morally superior light – with the disvalues attributed to another party (UKIP) by its critics (“white nativism”, “racial and ethnic intolerance”; no UKIP politician would say they espouse racial intolerance). It is hard to say without careful analysis how of the strong support for Labour among the Millennials and Gen X in the 2017 GE was due to the Labour manifesto pledges to support LGBTQ equality, women’s rights, anti-racism, animal welfare etc. Months before the GE2017 election campaign and release of the manifesto, polls show Labour having a strong lead among younger voters. Labour’s policy of abolishing tuition fees was targeted at the young, and provides a financial incentive to vote Labour. If I remember correctly, in every UK general election in the past decades, Labour always had a lead over the Conservatives among voters in the 18-24 age group. This lead was particularly wide in 2017 – perhaps a combination of perennial factors (the young tends to be more left-leaning and socially liberal; the young vote against the governing party as rebellion against authority figure) and special factors (reaction against Brexit, promise of abolition of tuition fees, policies and values espoused in the Labour manifesto)

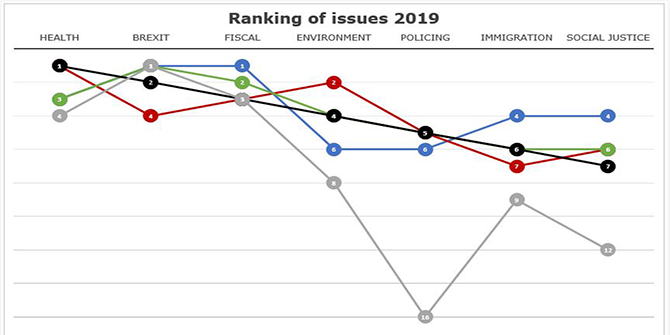

Figure 2 is interesting. However, I would like to see how age and socioeconomic variables were controlled for. Figure 3 is intuitive – the questionnaire items accurately mirror slogans used by UKIP and the Leave campaign. Norris concludes from figures 2&3 that the evidence suggests cultural issues deeply divide the electorate and factions within mainstream parties. But surely Figure2 only tells us about the electorate not the party factions?

Norris’ language of “authoritarian reflex” is consonant with work by the social psychologist, Jonathan Haidt, famed for his work on moral psychology. See his analysis of the conflict between the “internationalists” and “nationalists”: https://www.the-american-interest.com/2016/07/10/when-and-why-nationalism-beats-globalism/

Haidt cautions against labelling people as racist when they voice concerns over immigration. This just makes them turn to nationalist parties.

One needs to be careful with talk of “liberal consensus” which may turn out to be a “liberal delusion” as Prof. Danny Quah, former head of LSE Economics Department termed it (www.youtube.com/watch?v=GpNYJG_NZB8)

I’m a Brexit voter and consider myself a true progressive. I don’t see how we can preserve or indeed attain equal rights for women and gays if we bring many thousands of people into the country who believe it is a criminal act to be gay and who don’t believe that women should have the same rights as men.

Many older citizens campaigned for equality and see it might be threatened in the future.

There is a democracy deficit in the set up of the EU. We need to hold our politicians to account.

EU migration is overwhelmingly from young, white christians with progressive and liberal backgrounds, which contradicts the first part of your argument.

Given that the EU parliament is elected with proportional representation where every vote counts and the European council as the highest gremium consists of democratically elected heads of states, I find it a bit rich to accuse the EU of a democratic deficit when it comes from a country where the head of state is a monarch, the upper chamber is appointed and the lower chamber of parliament is elected with the pretty undemocratic First-past-the-post mechanism.

I suppose that you‘re against immigration in general (especially from muslims) and you just have not realized yet, that you‘re not a „true progressive“, but just another uninformed racist.

Well we know the lowest turnout to vote in the referendum was the young, they chose to abstain, we know that those with least knowledge are the easiest to fool, so the young were scared by the completely negative project fear campaign employed by remain. The comments made by the young in every discussion regarding the nations decision to leave reflect this as terms like Brexit car crash cliff edge disaster economic meltdown mass emigration job loss’ and all the other lies remain told. They even think that the electorate should be ignored by the government and we should stay in. The truth is we looked at the situation we looked at the past we looked at the future and with the knowledge and experience decided it was time to get out, the people who will mainly benefit from this are the young, because we had 41 and growing lost years due to eu membership.

True, the lowest turnout is nearly always among the young in all societies. But why assume that younger generations have the least knowledge?

Why not just assume that they have a different perspective towards open borders and the EU than their parents and grandparents, just like they differ in much else like music, clothes, and popular culture, attitudes towards religion, sexuality, and family life, and lifestyle preferences? Change plus ca change.

I think one always needs to bear in mind the possibility that the idealistic 18 and 19 year old voters enthusiastically voting Yes to stay in the Common Market in June 1975 were quite likely to be the same jaundiced 59 and 60 year old voters determinedly voting to Leave the European Union in June 2016.

True, there can always be age, period and generational (birth cohort) effects. Our book does test for this and finds that the main process of value change is generational ie people tend to stick with the values of their youth, so change on issues such as support for LGBTQ rights, global governance, and religiosity comes through the older generation leaving the population and the younger cohorts gradually taking their place.