A series of cuts since the Coalition government curtailed the welfare state, activating this way a range of existing economic grievances. As a result, in districts that received the average austerity shock UKIP vote shares were up, compared to districts with little exposure to austerity. Thiemo Fetzer writes that the tight link between UKIP vote shares and an area’s support for Leave implies that, had austerity not happened, the referendum could have been in favour of Remain.

A series of cuts since the Coalition government curtailed the welfare state, activating this way a range of existing economic grievances. As a result, in districts that received the average austerity shock UKIP vote shares were up, compared to districts with little exposure to austerity. Thiemo Fetzer writes that the tight link between UKIP vote shares and an area’s support for Leave implies that, had austerity not happened, the referendum could have been in favour of Remain.

Following the EU Referendum in 2016, a rich but mainly descriptive literature emerged studying the underlying correlates of Brexit. An important cross-cutting observation of such works is that Leave voting areas had been “left behind” from globalization, with the local population having been particularly reliant on the welfare state. In a new paper, I bring together broad and comprehensive evidence which suggests that austerity measures since 2010 may indeed have had a substantive impact on the outcome of the vote.

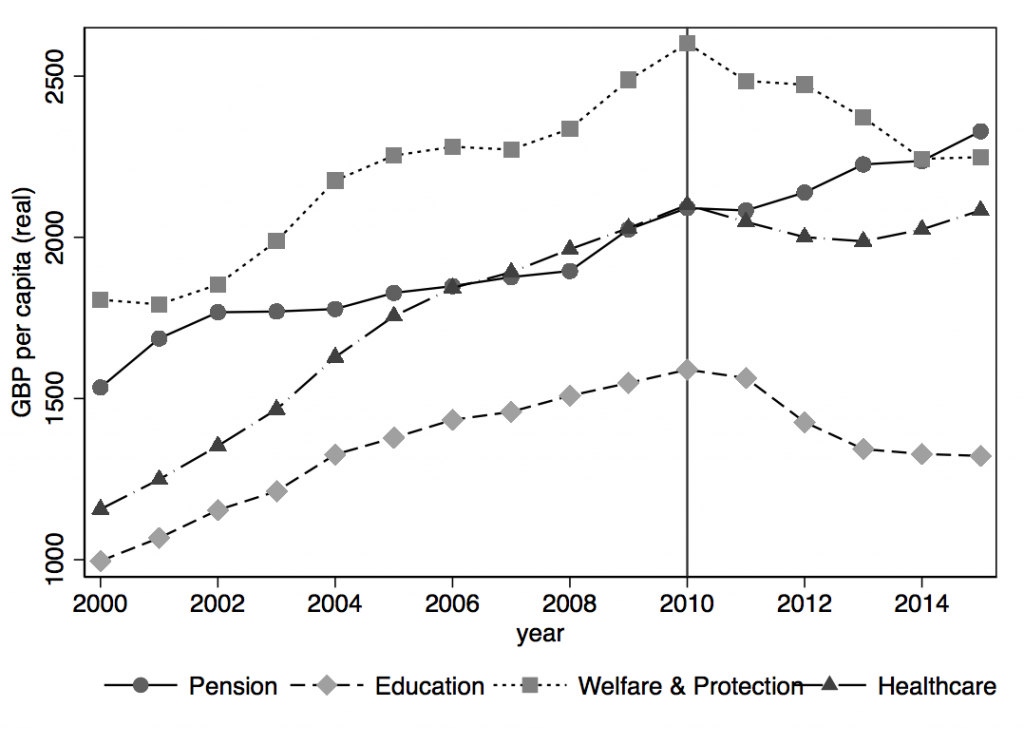

The austerity-induced reforms of the welfare state since 2010 have been extensive. Aggregate real government spending on welfare and social protection decreased by around 16% per capita; spending on healthcare flatlined; all while the ageing profile of the population was increasing demand for healthcare services. Further, spending on education contracted by 19% in real terms, while expenses for pensions steadily increased, suggesting a significant shift in the composition of government spending. At the district level, spending per person fell by 23.4% in real terms between 2010 and 2015, varying dramatically across districts, ranging from 46.3% to 6.2% with the sharpest cuts in the poorest areas.

Figure 1 – Overall public sector spending in GBP per capita (real).

Data are from HMRC and ONS.

Data are from HMRC and ONS.

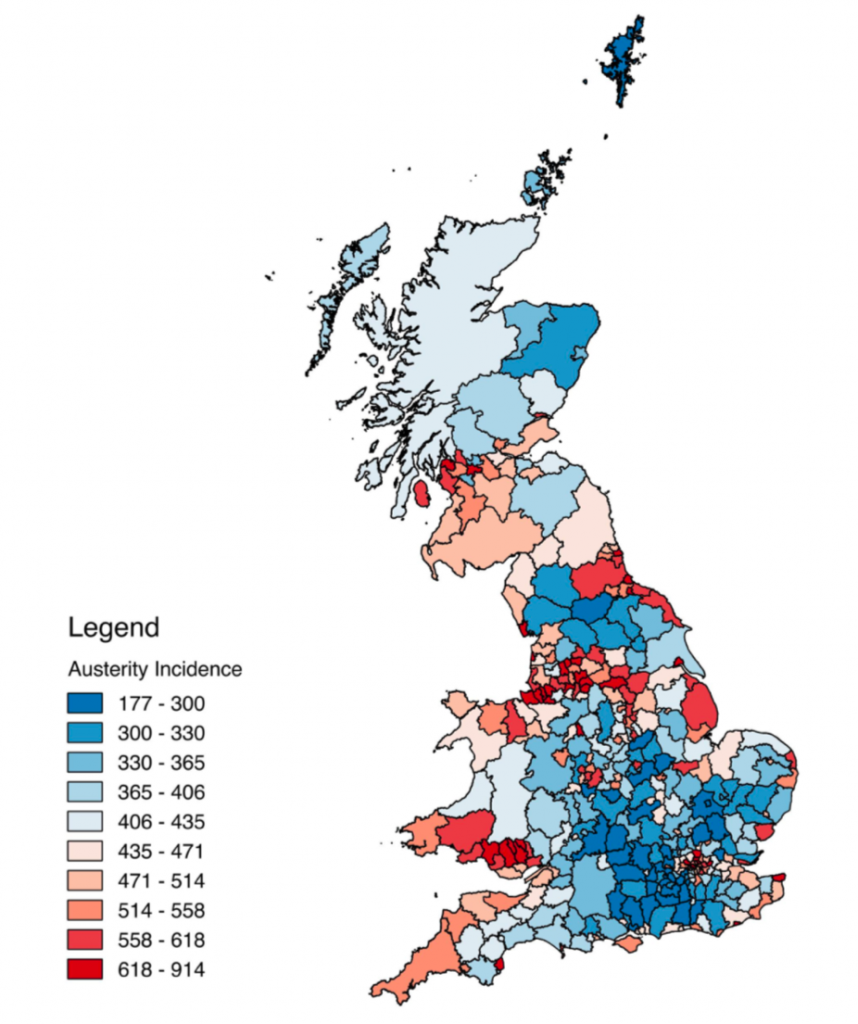

In 2013, it was estimated that many of the measures included in the Welfare Reform Act of 2012 would, on average, cost every working-age Briton around £440 per year. The impact of the cuts was far from uniform across the UK as is shown in Figure 2. It varied from £914 in Blackpool to just above £177 in the City of London. The overarching observation was that the most deprived areas where most severely affected by the cuts, as they had the highest numbers of people receiving benefits to begin with.

Figure 2 Distribution of austerity shock. The measure is expressed in financial losses per working-age adult per year.

Simulated by Beatty and Fothergill

Simulated by Beatty and Fothergill

Exposure to austerity had sizable effects, increasing support for UKIP across local, Westminster, and European elections. Estimates indicate that, in districts that received the average austerity shock, UKIP vote shares were on average 3.6 percentage points higher in the 2014 European elections and 11.6 percentage points higher in the most recent local elections prior to the referendum, compared to districts with little exposure to austerity. The tight link between UKIP vote shares and an area’s support for Leave implies that Leave support in 2016 could have been up to 9.5 percentage points lower and, thus, could have swung the referendum in favour of Remain, had the austerity shock not happened.

While working with aggregate data is appealing, it also comes with some caveats, as the estimated effects could be masking a host of other mechanisms. Yet, the political effects of austerity are also estimable when turning to individual level panel data. Individuals who were exposed to a set of welfare reforms shift to UKIP once they had experienced the benefit cut. One example of a reform studied is the so-called “bedroom tax”. The results suggest that households exposed to this tax shifted towards supporting UKIP, and experienced economic grievances as they fell behind with their rent payments due to the cut. Indeed, dissatisfaction with political institutions as a whole increased following such cuts, with affected individuals being more likely to think that their vote is “unlikely to make a difference” and that “public officials do not care” about them. In other words, by curtailing the welfare state, austerity has likely activated a broad range of existing economic grievances that have developed over a long period.

Identifying and quantifying the relative contributions of different factors that cause the underlying economic grievances, especially among the low-skilled, is an active field of research. For example, Colantone and Stanig suggest that trade integration with low income countries, by intensifying competition, has hurt manufacturing goods producing areas in the UK, which is why voters in these areas have been more likely to support Leave. Similar evidence, linking economic hardship due to trade-integration to populist or extreme voting is being documented in the context of the US and Germany.

Similarly, evidence is compounding that some forms of immigration do have small, but detectable effects on labour markets by curtailing wage growth at the bottom end of the wage distribution. There is also some evidence suggesting that automation, by reducing demand for low-skilled workers, can also suppress wage growth among the low-skilled. In the historical context, this type of (manual) labour-saving technological progress has been linked to political unrest. The rise of the gig-economy, zero-hours contracts etc. may also push people to become reliant on the welfare state to top up salaries. Each of these factors are likely to exacerbate the economic cleavages between the well-educated and the rest – a phenomenon often referred to as the growing skill-bias (see here or here) in labour markets.

The natural implication is well known to economists – trade integration (or globalization) and the welfare state are complements. In order to maintain continued public support for globalization, policy needs to deliver solutions for globalization’s losers. This can take the form of continued investment in education, training and designing a welfare system that can help individuals transition into new jobs.

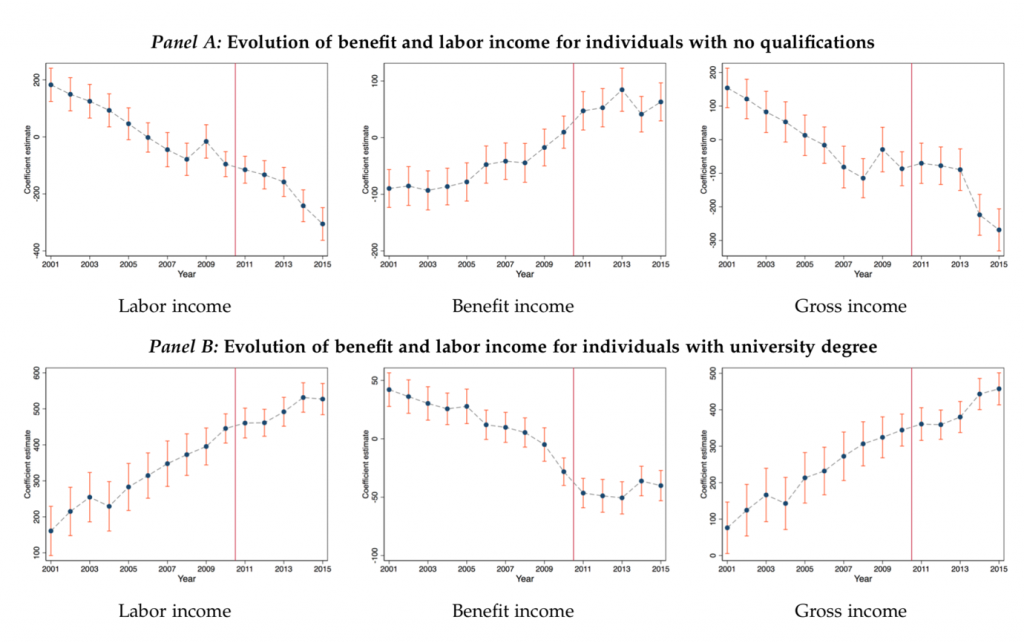

Figure 3 Trends in Labour, Benefit and Gross incomes for individuals with no formal qualifications compared to those with at least a university degree.

The figures are constructed using data from the BHPS and the USOC for those who are non-retired. We remove local-authority district by time effects as well as individual level fixed effects.

The figures are constructed using data from the BHPS and the USOC for those who are non-retired. We remove local-authority district by time effects as well as individual level fixed effects.

The paper shows that the UK welfare state seems to have been responsive (in some part) up to 2010, when austerity started to have an effect. This is illustrated in Figure 3. From 2001 to 2010, the UK had expanded benefit payments to those who became increasingly worse off as their labour incomes were declining relative to the rest of the population (left panel and central panel in the top row). As a result, their relative decline in gross incomes was halted. Yet, from 2010 onwards, the growth in benefit incomes came to a halt as austerity started to take effect, which the paper argues lies at the heart of the shift in public support towards UKIP, whose raison d’etre was Britain’s exit from the EU.

__________

Note: the above draws on the author’s longer paper on the topic.

Thiemo Fetzer is an Associate Professor in the Economics department at the University of Warwick.

Thiemo Fetzer is an Associate Professor in the Economics department at the University of Warwick.

All articles posted on this blog give the views of the author(s), and not the position of LSE British Politics and Policy, nor of the London School of Economics and Political Science. Featured image credit: Pixabay (Public Domain).

I am receptive to the account that the austerity measures during 2010-2016 contributed – alongside a multitude of other factors – to the Leave vote, by creating economic dissatisfaction which some Leave voters somehow misattributed to membership of the EU. However, I would question: (1) the author’s quantification of as much as 9.5% of the Leave vote could be traced to austerity measures; (2) his attribution of the increase in UKIP votes in the local elections and general election primarily to austerity measures and curtailment of the welfare state; (3) his reliance on research by Beatty and Fothergill (funded by Oxfam and Joseph Rowntree Foundation, both of which have organisational bias towards support for welfare state) to quantify effect of austerity according to UK constituencies.

(1) “9.5 percentage points lower…had the austerity shock not happened.”

The extent and speed of austerity, especially in light of the leeway given by sharp and continually reduction in UK government borrowing costs since 2010, probably was a political choice, but having to implement some form of austerity by reducing public expenditure as most EU countries had to do given high deficits and debt levels following the Great Recession, probably was not. The UK deficit in 2010 was 10% of GDP. Had it stayed this level during 2010-2016, it would have added 60% to debt all else equal, with risk of sovereign debt crisis if nothing was done. At the 2010 election, all the 3 main political parties acknowledged of the need for some form of austerity (see for example the party leaders debates in 2010). So while the extent and pace of austerity were up for debate, the necessity for austerity was not. Hence the question that needs to be answered here is not the counterfactual “had austerity not happened” (not a realistic option given the impact of the recession), but “had the extent of austerity been more moderate”, would UKIP experienced a smaller rise in support, and would the Leave vote been lower. It is plausible that a moderate form of austerity, given severity of the recession and stagnation of wages in public and private sectors, would still have created economic discontent and drove voters to the anti-establishment party UKIP – even if Fetzer’s hypothesis is correct. Moreover there are reasons to doubt his hypothesis: the rise of UKIP as a reaction against austerity fails to explain why those new UKIPers didn’t instead flock to the Green Party which was most opposed to austerity and portrayed itself as an anti-establishment voice on the Left.

While UKIP voters overwhelmingly voted for Leave, it does not follow that had the UKIP voters voted for another party, they would have voted to Remain. Leave voters were drawn from all the major parties including the pro-EU party SNP. Hence UKIP voters could have characteristics that drew them to vote Leave, even if they counterfactually did not vote UKIP. Therefore the 10% headline grabbing estimate is likely to be a gross over-estimate.

The EU Referendum exposed a dimension in UK politics that cuts across the traditional Left-Right divide framed around the size of the state. The new dimension can be characterised as divide between electorate with nationalistic sentiments versus those with global outlook. This cross-cutting means the referendum results are open to both a leftwing and rightwing narrative.

(2) Was the rise in support for UKIP in the elections prior to the EU referendum attributable to curtailment of the welfare state?

UKIP under Farage’s leadership is commonly classified as a rightwing populist party. UKIP policies at 2015 General Election proposed even more severe austerity measures than the Conservative: “Ensure Treasury sticks to plan of liminating the deficit by the third year of the next parliament, with a surplus after that”, “Lower the cap on benefits”, “Limiting child benefit to two children for new claimants”. Either UKIP voters were pretty ignorant and were lured into voting for a party advocating policies against their own preferences, or they genuinely supported curtailment of the welfare state. UKIP proposes many policies to cut welfare state (e.g. in-work benefits) targeted at immigrants, and talked much about slashing Foreign Aid budget. UKIP voters probably have more nationalistic sentiments than the average voter.

(3) Impact of austerity by UK constituencies

Can we infer the attitude of UKIP voters to austerity from the 2017 General Election, when the UKIP vote collapsed? It appears roughly half of the collapse in UKIP vote at 2017 GE went to Labour (with policies signalling end of austerity) and other half to Conservative (continuation of austerity). The split is not uniform across constituencies – it appears in many areas of southern England, a larger share of UKIP vote went to Labour, whereas in northern England, a larger share went to Conservative. This pattern doesn’t fit the the impact of austerity map cited by the author.

How do you eliminate other factors from your analysis? How do you know that more people didn’t vote to remain due to the austerity effect in order to stay under the perceived protective umbrella of the EU? Did you test what impact austerity measures had on the remain vote? Would those who voted remain have done so in the absence of austerity?

Maybe people saw what was happening on the continent post- 2008 and determined that this wasn’t for them?

@David Roberts, I am not persuaded by Fetzer’s hypothesis that UKIP support is explained by UKIP voters’ experience and reaction against austerity and welfare cuts, nor the importance he assigned to the level of UKIP support across UK constituencies in explaining the Leave vote. Reasons for my scepticism include: (1) the welfare cuts in his study e.g. bedroom tax, disability living allowance, council tax benefit affect only a small percentage of population, unlike the 26.6% of UKIP vote share in EU elections 2014, or the 13% in UK GE 2015, hence it seems implausible these welfare cuts accounted for a large part of UKIP vote; (2) UKIP manifesto 2015 proposed more severe austerity policies and more welfare cuts than the Conservatives; (3) I am sceptical the British welfare state has ever been well-designed and well targeted to compensate the losers to globalisation (e.g. from UKIP’s GE2015 policies and David Cameron’s negotiations with EU post 2015 election, it appears some of the electorate with anti-EU sentiments, resent the fact in-work benefits are given EU migrants, hence increasing in-work benefits when UK remains part of EU could exasperate anti-EU sentiments).

However, from skimming his 100-page paper (https://warwick.ac.uk/fac/soc/economics/research/centres/cage/manage/publications/381-2018_fetzer.pdf), I think Fetzer has gone some way to answering your first question and he has interesting ideas and econometric methodology not explored in other research. As to your other questions, as I understand it, his research is not attempting to account for most of the 17mln Leave votes (I think some people dislike what they saw happening in the EU e.g. eurozone crisis, Merkel’s open-door immigration policy creating pull-factor on economic migrants from impoverished northern African and Middle-East countries; high-profile cases of terrorism in Europe where a few of the perpetuators were recent migrants), but the component closely related to UKIP support. As to possible impact of austerity on accounting for some of the Remain vote, I suspect he ignored this possibility altogether. But suppose he is right that the geographical incidence of austerity explains UKIP vote, and UKIP vote in turns explains Leave vote, then austerity has a *net* positive impact on increasing share of Leave vote – so indirectly it shows whatever positive impact austerity has on Remain vote, it is outweighed by its positive impact on Leave vote.

A classic can confusion between correlation and causation. Austerity included benefits cuts. The areas where there are more people dependent on social welfare are also places that have “enjoyed” high immigration, many of these people have suffered higher housing costs, diminished availability of public services and fewer low skilled job opportunities and are understandably frustrated. The tail does not wag the dog.

Kate Heusser is exactly right, well said indeed.

Sigh. Autocorrect!

That should read:

A classic case of confusion….

Again, analysts trying to find a reason other than a wish to leave the EU for the ‘Leave’ vote. Doesn’t UKIP’s name give a clue – their apparent popularity disappeared as soon as the referendum result was declared – by last year’s unnecessary election, even the dismal campaigns of both main parties couldn’t induce people to vote for UKIP. If ‘austerity’ and Tory policies had been the motivation, then the Conservative vote would have collapsed. It didn’t. It increased. It was the best showing – in terms of votes cast AND percentage, for decades. Labour’s vote strengthened even more – and it was UKIP’s vote that collapsed. There’s no mystery there; BOTH main parties pledged in their manifestos to honour and execute the referendum result. The voters voted for independence.

Hi. It should really be pointed out that all EU member states must conform to EU austerity policy that is embedded in EU Treaty (TEU Art 126) which is also directly linked to the EU Stability and Growth Pact stage 1. The UK included. Therefore if EU austerity policy did not happen, then there might have been 9% less support for Brexit.

Thanks.

Article 126 was in existence when the UK government deficit exceeded that of today’s during Margaret Thatcher’s fight against inflation during the 1980s. Could you please cite where and when the UK was penalised under this article since joining the EU?

Stephen did not mention ‘penalise’ but treaty ‘obligations’ are followed and on overall economic policy – ie ‘austerity’ – the Treasury does so slavishly. I pointed this out in the first Post here.

That is the point of being in the EUmess.

I would suggest UKIP benefits directly because of EUropean Policies and behaviours which produce negative outcomes for most people.

1) ‘Austerity’ measures were imp[osed by Osborne and the Treasury being directed by the European Central bank and the othe other EuroCommission economic institutions under the centralising Euro Ideal of ‘one size fits all’ so hard luck Greece and Hartlepool!

2) ‘Welfare Benefit decline’ which is in effect a supplement to low wages as ‘In Work benefits’ cannot expand exponentially in relation to the real cause which is the completelty unrestricted Freedom Of Movement of the non-skilled and low-skilled of eastern and southern Europe, it caused a decline in the movement of employment across regions within the UK, to the detriment of poorer regions where there used to be a method to ‘escape to employment’. This FoM causes both a fundamental distortion of the UK labour market to the detriment of British nationals (including of course the previous wave of immigrants) and decline of collective bargaining power in the private sector. It also means that its effect on the overall welfare budget is exascerbating budgets in that all the new arrivals and their dependents are reliant on this supplement apart from their pressure on health, welfare, social services, local education and housing provision.

There is no ‘benign’ effect to EUro policy.

@Tony – where is the evidence to prove the policy of austerity was imposed by the European Central Bank? Greece cannot be compared to the UK. The UK was not obliged to carry out austerity measures – that came from the Tories economic policy alone. Unless you can prove otherwise, I’d wager your argument is flawed.