Whilst political attention is largely trained on the party politics and votes at stake in Hartlepool, there is much that policymakers can learn by looking at the North East constituency. Displaying many of the characteristics of the kinds of places the government wants to ‘level up’, Hartlepool serves as a reminder of the scale of that challenge, writes Aveek Bhattacharya.

Whilst political attention is largely trained on the party politics and votes at stake in Hartlepool, there is much that policymakers can learn by looking at the North East constituency. Displaying many of the characteristics of the kinds of places the government wants to ‘level up’, Hartlepool serves as a reminder of the scale of that challenge, writes Aveek Bhattacharya.

There’s nothing like a by-election to draw political attention to a place, and Hartlepool is fascinating for poll-watchers. What would a loss mean for Starmer’s Labour? Will the Conservatives see a ‘vaccine bounce’? But Hartlepool is interesting for other reasons too. It offers a snapshot of the policy challenges facing the UK: poor health, stagnant wages and poverty, under-investment and fraying social fabric. That’s why we at the Social Market Foundation have produced a set of key facts and figures about the constituency and the major policy issues it faces. Irrespective of who wins, the local data tells us policymakers have a mountain to climb.

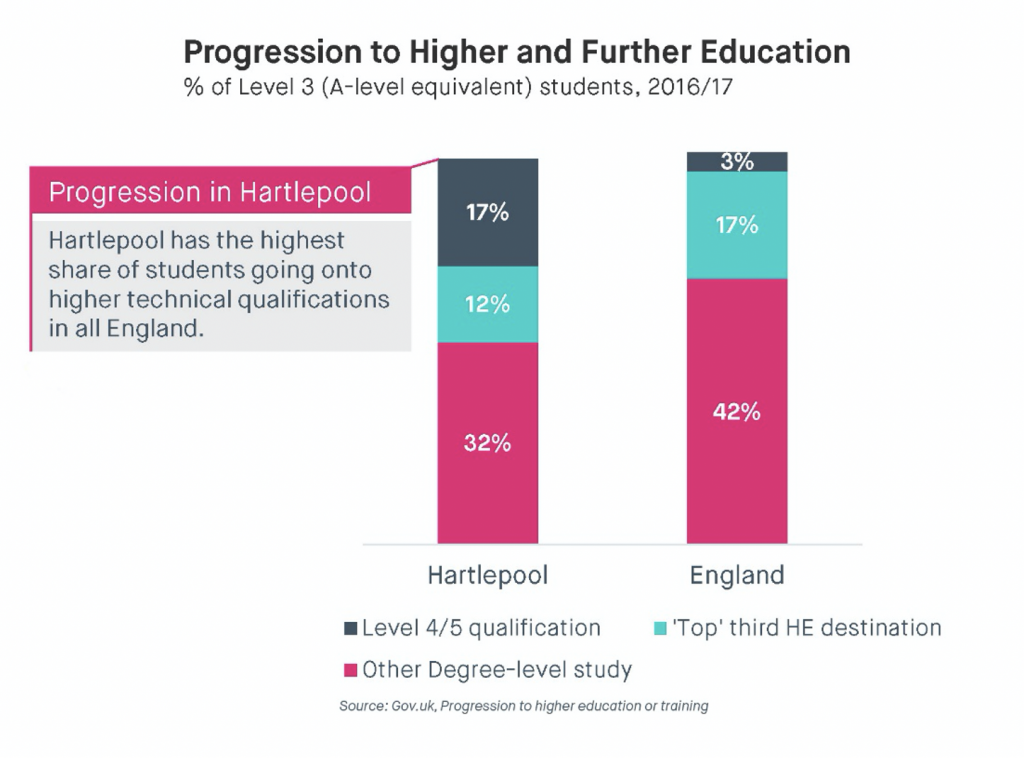

Let’s start with the relatively good news: education. Hartlepool stands out in a number of ways. The town was described by the government’s Social Mobility Commission as an ‘early years’ hotspot, and its above-average preschool outcomes show that deprived areas don’t always do worse. Educational strength continues through primary school, where 91% of children are in schools rated ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ by Ofsted, above the national average. However, the picture is less rosy at secondary level, where only 43% of students are at ‘good’ and ‘outstanding’ schools, and exam results are worse than the rest of the country.

Where Hartlepool really shines, though, is in post-18 education. In 2016/17, it had the highest share of students going on to do higher technical qualifications (vocational courses and apprenticeships) anywhere in England: 17% compared to 3% nationally. With the government belatedly recognising the value of such courses – putting them at the heart of its recent Skills White Paper – Hartlepool should be a model for the rest of the country. However, it will be hard for other places to emulate without a significant increase in support and resources – per student spending in further education fell 12% between 2011/12 and 2019/20, and the sector was incensed recently by the ‘clawback’ of adult education funding.

Hartlepool has felt the full brunt of austerity in other areas too. As of 2018/19, it was one of eight local authorities to have cut all funding for bus services. In the past decade, passenger journeys have fallen by 28%. That decline is just a more extreme version of what is happening elsewhere in the country: across the whole of England, the figure is 18%. Hartlepool thus illustrates the lost ground that must be made up by the government’s recent ‘Bus Back Better’ strategy.

Hartlepool has felt the full brunt of austerity in other areas too. As of 2018/19, it was one of eight local authorities to have cut all funding for bus services. In the past decade, passenger journeys have fallen by 28%. That decline is just a more extreme version of what is happening elsewhere in the country: across the whole of England, the figure is 18%. Hartlepool thus illustrates the lost ground that must be made up by the government’s recent ‘Bus Back Better’ strategy.

Public health is another area which has felt the axe. Grants have been cut by 22% in the last five years, even as money has been poured into shoring up the NHS, though spending on prevention is estimated to be four times as cost-effective as spending on healthcare. Again, Hartlepool represents something of a worst-case scenario. It has the second highest proportion of adults classified as overweight or obese, the fifth highest share of smokers, and the 13th highest rate of alcohol-specific deaths.

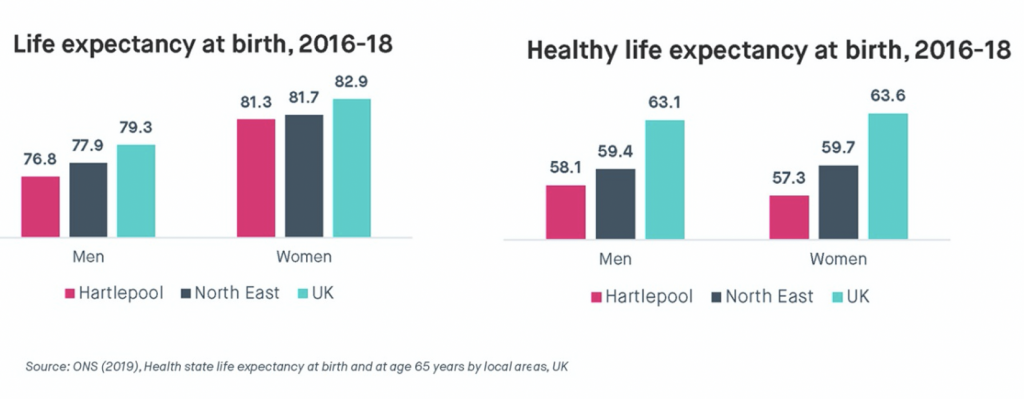

A lack of progress on those ‘lifestyle risk factors’ helps explain the town’s relatively poor health. Hartlepudlians live around two years less than the rest of the country on average, but have far worse healthy life expectancy. Men in Hartlepool can expect to have around 58 years of healthy life compared to 63 in the rest of the country; women 57 against a national average of 64. But Hartlepool is not an isolated case: life expectancy, especially for the poorest, has been stagnating. Throughout the 20th century, life expectancy rose by around three years in a typical decade. In the 2010s, we gained less than a year. For women in the most deprived areas, life expectancy fell. COVID-19 has convinced many, including the Prime Minister, that the country needs to take health more seriously. Hartlepool, with a death rate from the virus 27% above the national average, shows why.

At the root of Hartlepool’s challenges is poverty. Average earnings are 7% lower than in the rest of Britain, and in both Hartlepool and the country as a whole inflation-adjusted earnings are lower today than in 2008. Weak economic performance has driven an increase in child poverty: 22% of Hartlepool children were in low-income households in 2018/19, up five percentage points from 2014/15. The pandemic has worsened hardship: at the Social Market Foundation, we estimated that 18% of children went hungry last year in Hartlepool.

More broadly, Hartlepool exemplifies concerns about weakening social ties and community that apply to the UK as a whole. It ranks sixth from bottom in the think tank Onward’s ‘Social Fabric’ Index, reflecting low trust, civic participation, and social engagement. It is no surprise, therefore, that the local council has joined the campaign for a ‘community wealth fund’ to invest in the town and improving public spaces. What remains to be seen is whether spending on this sort of infrastructure can shape social norms and really be effective in bringing people together.

Politics should not be about winning elections. It should be about improving people’s lives. The next few weeks will see litres of ink spilled on the horse race of the Hartlepool by-election. But what really matters is the work of reducing poverty, improving health, providing high-quality educational options and good transport links and strengthening community, in Hartlepool and places like it around the UK.

____________________

Note: The above draws on the Social Market Foundation’s briefing ‘So now you give a monkey’s? The policy wonk’s guide to Hartlepool’, available here.

Aveek Bhattacharya (@aveek18) is Chief Economist at the Social Market Foundation, and near completion of a PhD in Social Policy at the LSE.

Aveek Bhattacharya (@aveek18) is Chief Economist at the Social Market Foundation, and near completion of a PhD in Social Policy at the LSE.