The EU is considered to be the world’s largest public donor and it has claimed to use public funds to promote the participation of organised interests in public policy. Drawing on a new study, Michele Crepaz and Marcel Hanegraaff illustrate that despite claims of balance in how funding is distributed, organisations with larger resources and more experience of making funding applications are still far more likely to be successful in bidding for funds.

The EU is considered to be the world’s largest public donor and it has claimed to use public funds to promote the participation of organised interests in public policy. Drawing on a new study, Michele Crepaz and Marcel Hanegraaff illustrate that despite claims of balance in how funding is distributed, organisations with larger resources and more experience of making funding applications are still far more likely to be successful in bidding for funds.

Every year, the EU makes use of an approximate sum of €20 billion to fund more than 70,000 organisations worldwide, making more than 30,000 budgetary commitments. These are large numbers, considering that EU funds represent roughly 20% of the total EU budget expenditure.

The general objective of these funds is to support the implementation of a project (called project funding) or to support an organisation’s management and its administrative capacity (labelled core funding). Many organisations, from firms, to universities, to non-governmental organisations (NGOs), associations, charities and even national public bodies rely on these funds in order to coordinate their policies in various fields. Funds are allocated to all policy areas, from business and industry, to climate action, animal welfare, youth and sports. It’s a successful system that has proven efficient in strengthening the EU’s socio-economic performance.

The European Commission – the main institution behind the management of the funds – has often associated the use of funds with the objective of improving input and output legitimacy in decision-making. In other words, funds should help European civil society to develop, so that even the weakest of the organisations can participate in the European project and support its activities. With these considerations in mind, we have assessed two very simple questions in a recent study: Is it true that EU funds level the playing field for weaker organisations? If we look at data, which organisations are more likely to obtain funding?

At first, students of voluntary organisations had answered positively to both questions (at least in part) providing a picture of the EU funding mechanism as a balanced and redistributive system. Nevertheless, EU interest group scholars have, in recent years, provided a different interpretation of EU politics: better-endowed interests find it easier to participate in policy-making. However, in drawing this conclusion, scholars had not considered EU funds.

This is why, in 2016, we surveyed 290 organisations (with a response rate of 38.7 per cent) registered in the European Transparency Register (TR) about their past and on-going applications for funding with the objective of discovering which organisations are, on average, more likely to obtain funding. We are the first to have asked organisations specifically about their applications, and are also the first to interpret the attainment of these funds as the Commission’s intention to balance the inputs of organisations and guarantee an open participatory political system for all interests.

Why have we sampled organisations from the Transparency Register? It is a requirement for interest groups wishing to lobby EU institutions to disclose the attainment of EU grants in the Transparency Register. Currently, approximately 20% of the registered interest groups receive funds from the EU. This is the focus of our analysis, as it ties directly into our main question and allows us to evaluate whether existing biases in system of interest representation are reflected in the distribution of EU funds.

Sixty years of political science research has shown that, on-average, better-endowed organisations, representing economic (rather than public or professional) interests tend to dominate the system of interest representation. If we had found that the same organisations were also the ones that were more likely to obtain EU funds, then we would have; first, challenged any view that depicts the EU subsidy system as redistributive; and second, stressed the importance of the analysis of EU funds in the study of interest groups.

Of the 290 surveyed organisations, 172 had applied for EU funds since 2015: 52 had obtained the funding while the remaining 120 were unsuccessful. What factors make those 52 applications more successful than the others? We found that organisations with larger budgets and a higher success rate with past applications were more likely to attain EU funds, controlling for the type of organisation, its perceived need for funds, its organisational capacity, geographical origin and level of eurocentricsm. In other words, the probability of a ‘rich’ organisation winning EU funds is almost twice that for a ‘poor’ one.

Figure 1: Size of an organisation’s budget and their predicted success in an EU funding application

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in the Journal of European Public Policy

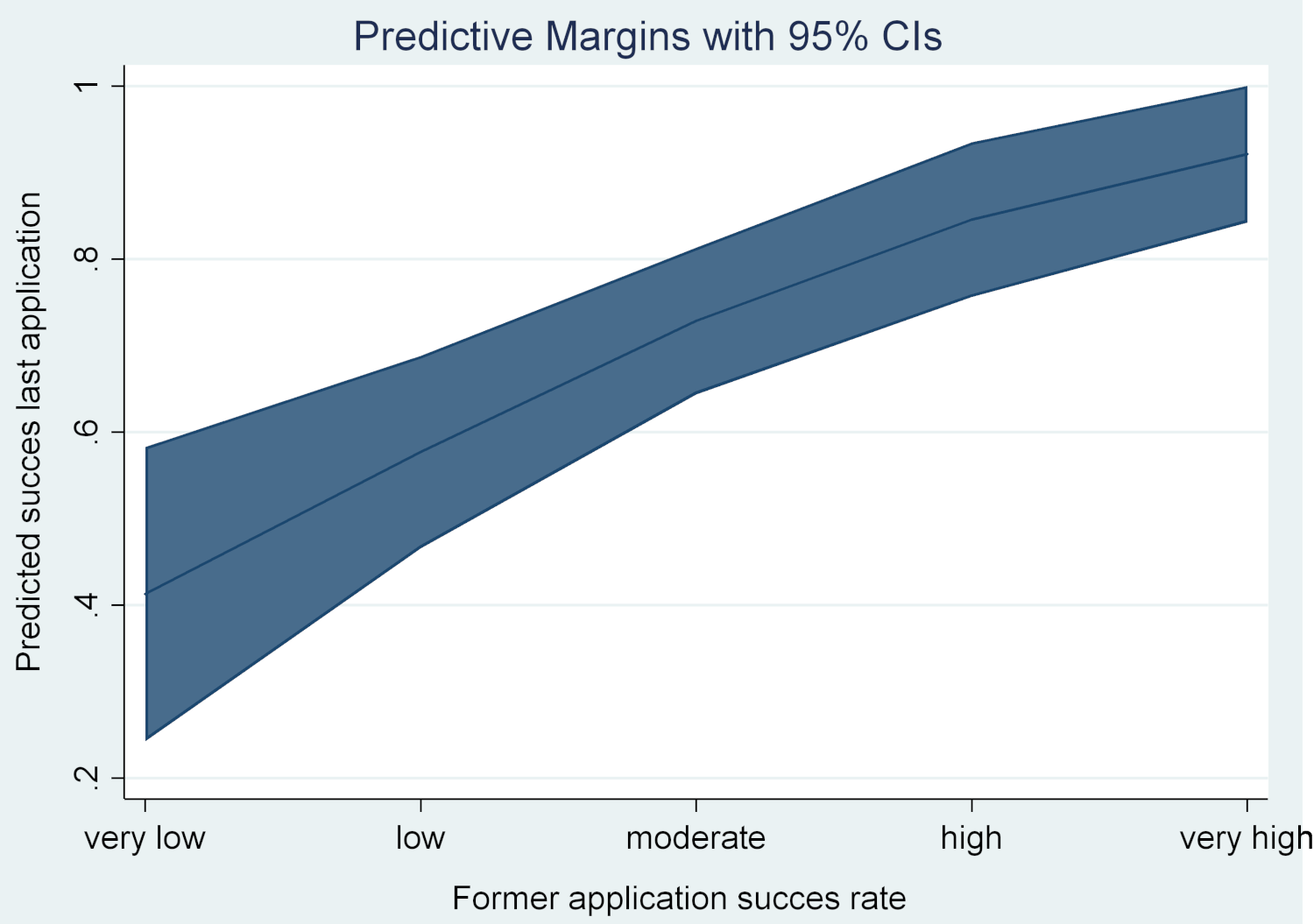

A similar picture emerges when the organisation’s success rate with past applications is considered. The probability of winning EU funding for an organisation with a successful track-record is more than double that for an organisation with little or no past experience with applications.

Figure 2: Past and predicted success with EU funding applications

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in the Journal of European Public Policy

What do these results tell us about the system of EU funds? First, the view of the EU funding system as being dominated by the principles of associative democracy is not accurate. On the contrary, the EU funding system seems to be dominated by the same biases that scholars of systems of interest representation have described for years: better-resourced organisations and insiders tend to dominate the political stage.

We might be tempted to give an elitist interpretation of our results and claim that, once again, political processes have been controlled by a small number of players. However, this would be simplistic. We believe that a different interpretation of our results offers a more nuanced understanding of the EU funding system.

Better-resourced and more experienced organisations are better equipped to write strong proposals for EU funding. Obviously, this puts them in an advantageous position compared to less-resourced organisations with little or no experience with the application system. In addition, the European Commission has a relatively small bureaucracy to allocate the funds and monitor whether they have been well spent. By giving funds to better-resourced and more experienced organisations, the Commission might reduce its monitoring costs.

While this behaviour certainly reduces the burden on the Commission’s bureaucracy, there are still potential negative consequences. Although richer and more experienced organisations will, over time, be more likely to obtain funding, poorer and less experienced organisations will remain outsiders. Our data already shows that low levels of resources and professionalisation, and fewer experiences with funding are associated with a lower probability of filing an application for funding. As a result, without a proper incentive structure, weaker groups will file fewer applications, and see their applications defeated by the ones submitted by better-resourced and more experienced interest groups.

If the Commission wishes to model and shape European civil society in the way it claims to do, then it should consciously make use of its demand-side forces. This would mean: 1) empowering its bureaucracy in a way to monitor and support the implementation of ‘high-risk’ projects for less-resourced and less experienced organisations; and 2) providing support to weaker organisations in the preparation and submission of grant applications.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying study in the Journal of European Public Policy

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Lore & Guille (CC BY 2.0)

_________________________________

Michele Crepaz – Trinity College Dublin

Michele Crepaz – Trinity College Dublin

Michele Crepaz is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at Trinity College Dublin.

–

Marcel Hanegraaff – University of Amsterdam

Marcel Hanegraaff – University of Amsterdam

Marcel Hanegraaff is an Assistant Professor at the University of Amsterdam.