The campaign for the European Parliament elections on 23-26 May offers an opportunity for key EU policy areas to be debated. Yet as Anna Nadibaidze writes, the issue of EU enlargement in the Western Balkans has so far remained far from the agenda. She explains that with public opinion focused on other topics and both mainstream and Eurosceptic parties lacking enthusiasm for rapid enlargement, the process is likely to slow in both the shorter and longer term.

The campaign for the European Parliament elections on 23-26 May offers an opportunity for key EU policy areas to be debated. Yet as Anna Nadibaidze writes, the issue of EU enlargement in the Western Balkans has so far remained far from the agenda. She explains that with public opinion focused on other topics and both mainstream and Eurosceptic parties lacking enthusiasm for rapid enlargement, the process is likely to slow in both the shorter and longer term.

The campaign for the European Parliament elections has already begun, and unsurprisingly, the issue of EU enlargement, specifically in the Western Balkans, has barely been mentioned. With the Brexit impasse and a number of other pressing issues to solve, enlargement is not a priority and will remain on the sidelines, at least in the short term until a new European Parliament and Commission are formed.

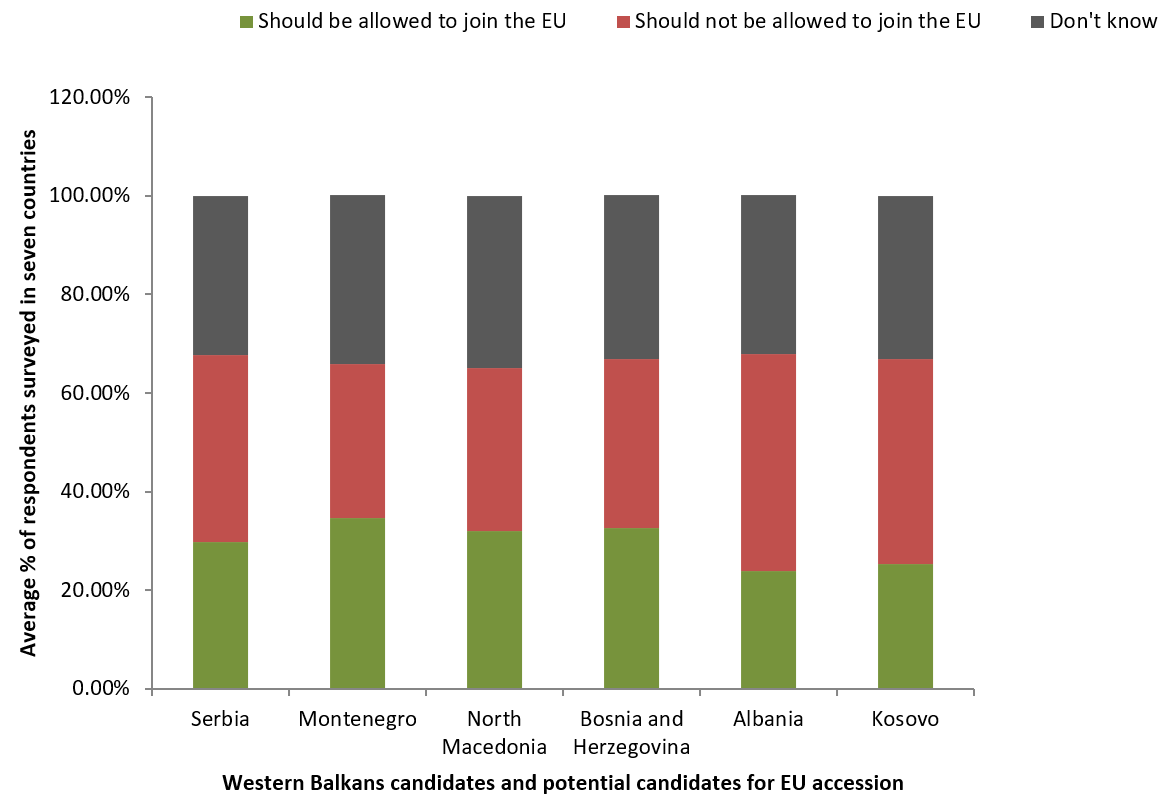

It is not a particularly popular topic among the European public. According to a YouGov poll looking at attitudes towards enlargement in six EU member states (Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Sweden and the UK) as well as Norway, in most of these countries, there are more people who believe that Romania’s EU membership was a mistake than people who do not. The prospects of the six Western Balkans candidates are also viewed with a degree of scepticism by the public in the countries surveyed.

Chart: Attitudes toward Western Balkans enlargement (selected European countries)

Note: Average calculated from results of YouGov/Eurotrack survey conducted in seven European countries (Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, Norway, Sweden and the UK) in December 2018.

Building upon these tendencies in public opinion, it has become easier for Eurosceptic and populist parties to use the ‘threat’ of enlargement in their anti-EU and anti-immigration rhetoric. The topic is therefore likely to be sidelined for the duration of the campaign, both by the main centre-right and centre-left parties, but also by the EU’s institutions.

Romania, currently holding the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU, stated it plans to focus on the topic of accession only after the European elections. Even the publication of the Commission’s annual reports on the progress of the candidate countries has been delayed from the usual date in April to the end of May. This is probably to avoid contributing to the populist cause at such a sensitive moment, when polls suggest an increasing number of seats could be won by Eurosceptic parties.

After the elections, when Finland takes over the presidency in July, the Union will be too preoccupied with the formation of new institutions, the (possible) finalisation of the Brexit process and the next stages of the Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) discussions. The accession process in the Western Balkans is expected to be revived only when Croatia, itself the newest EU member state and formerly part of Yugoslavia, takes over in 2020.

How can a new European Parliament influence the accession process?

While the European Commission conducts accession negotiations and monitors candidates’ fulfilment of criteria, the European Parliament also plays a key role as in the end it has to give the green light to the final terms of accession. Its approval is needed for the financial resources allocated to the Instrument for Pre-Accession Assistance (IPA) in the MFF. The Parliament also publishes positions and resolutions which have considerable influence on EU policy.

According to current polls, the new Parliament is predicted to be more fragmented, with the mainstream centre-right European People’s Party (EPP) and centre-left Socialists and Democrats (S&D) groups facing significant losses. This would mean more complex decision-making and an increasing need to forge coalitions.

Despite this fragmentation, there is a general lack of enthusiasm towards enlargement across the political groupings. The EPP – which is likely to win the largest amount of seats – states that it supports “the concrete European perspective of the Western Balkans” and helping “countries in the region improve their prosperity, as long as they adhere to European standards and achieve progress in the rule of law and the fight against corruption.” The largest party in the EPP, Germany’s ruling Christian Democratic Union (CDU), advocates “deepening” EU reforms before “widening” the Union, and stands against any enlargement until 2024.

The S&D group and the Liberals and Democrats (ALDE) support the Western Balkans’ accession path, but are strict on pushing for reforms in the region and are clear that the process must be based on merit. The European Greens also support increasing EU engagement with the region, but avoid giving details such as concrete dates of accession. French President Emmanuel Macron’s La République En Marche party has been constantly pushing for further reform of the EU before accepting new members, explicitly ruling out the possibility of any accession before 2025.

Most Eurosceptic and populist parties are opposed to EU enlargement, although they do not hold a unified position, as is the case with other foreign policy matters including the recognition of Kosovo and relations with Russia. Anti-immigration parties such as the Brothers of Italy have a strict stance against the accession of countries where the population is primarily Muslim, including Albania. The French National Rally argues that the EU must put a stop to enlargement.

There is cross-party expectation that enlargement is unlikely to happen anytime soon. This was demonstrated at the televised debates of French parties’ candidates for the European elections, where ten out of thirteen party candidates said they were against Serbia – who is currently at the most advanced stage of negotiations – joining before 2025, citing the need for reforms on both sides before such a step can take place.

Next steps

At the next European Council summit in June, EU leaders are due to decide unanimously upon opening accession negotiations with candidate countries Albania and the recently renamed North Macedonia. Following the Prespa Agreement with Greece, there is now a more positive attitude towards North Macedonia’s accession. However, as mentioned above, the governing parties in France and Germany do not support enlargement in the short-term, and there are suggestions that France is still hesitating about giving the green light. Serbia also expects the opening of two new accession chapters in June.

Declining either one or both of these decisions would be risky both for the region and for the EU. It would mean the EU failing to maintain its soft power rhetoric and its policy of ‘giving carrots’ to acceding countries. This is especially important with North Macedonia, where a lot of effort was put into implementing the Prespa Agreement with the specific goal of beginning the accession process.

The EU would risk losing leverage over other situations in the region, for instance the Serbia-Kosovo normalisation dialogue. Bilateral relations remain tense as Kosovo maintains its 100% tariffs on Serbian goods, despite Brussels saying the tariffs must be suspended in order for the dialogue to continue.

Progress on the enlargement front will take time, depending on the composition and leadership of the next European Commission, and who becomes the next Commissioner for Enlargement and European Neighbourhood Policy. Overall, it is unlikely that the newly composed EU institutions will radically change their approach towards the Western Balkans. Public opinion remains focused on other issues, and both mainstream and Eurosceptic parties lack enthusiasm for rapid enlargement. The EU will maintain a certain level of commitment, but the process is likely to slow down in both the short and longer term.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image: High Representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy and Vice-President of the European Commission Federica Mogherini attending a session of the Serbian parliament in Belgrade in 2017, Credit: EEAS (CC BY-NC 2.0)

_________________________________

Anna Nadibaidze – Open Europe

Anna Nadibaidze – Open Europe

Anna Nadibaidze is a research and communications associate at the think tank Open Europe. She holds an MSc in International Relations from the London School of Economics.