Political consultancies account for almost 10 per cent of the organisations present on the EU’s ‘Transparency Register’, which registers companies and individuals involved in lobbying the EU’s institutions. In a new study, Oliver Huwyler takes a closer look at the clients of these consultancies. He finds they are mostly firms and business associations, but that they rely on “hired guns” for very different reasons.

Political consultancies account for almost 10 per cent of the organisations present on the EU’s ‘Transparency Register’, which registers companies and individuals involved in lobbying the EU’s institutions. In a new study, Oliver Huwyler takes a closer look at the clients of these consultancies. He finds they are mostly firms and business associations, but that they rely on “hired guns” for very different reasons.

The growth of the EU’s market for political consultancy is largely linked to the deepening and widening of European integration. For 1999, German sociologist Christian Lahusen reported 290 active consultancies. Now, more than 20 years later, this number is well above a thousand. When the EU enlarged its borders and expanded its decision-making competences, interest groups flocked to Brussels – and consultancies followed.

The business model of political consultancies is to offer bespoke services for interest representation. Their support covers all steps ranging from monitoring the legislative agenda and providing an early-warning system, to carrying out the actual lobbying strategies. To learn more about the demand for such services, I sent a survey to 396 interest groups from 32 countries I knew had been lobbying on specific draft policy proposals by the European Commission. In my questionnaire, I asked them whether their organisation had bought certain consultancy services in this context.

The results revealed consultancy hiring to indeed be quite wide-spread. More than a quarter of the interest groups in my sample had gotten help from political consultancies when they lobbied on a particular proposal. When I inquired about any collaboration with political consultancies in the past, this number rose to almost 50 per cent.

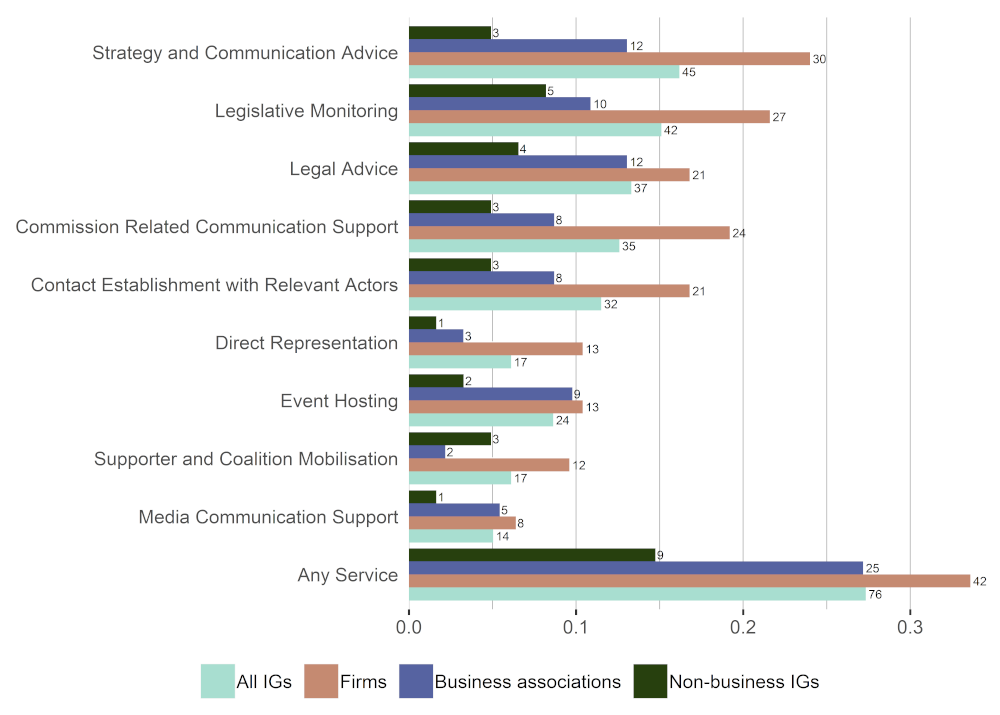

As the survey revealed, interest groups’ interest in consultancy support is relatively skewed towards certain services (Figure 1). By far the most popular services are aimed at strategic advice, legal counsel, and monitoring. A common feature of these tasks is that they relegate consultants to the background – out of the sight of policymakers and other interest groups. In the same vein, having consultants act as intermediaries between interest groups, the Commission, or other stakeholders is the service that is the least in demand.

Figure 1: Proportion of interest groups buying certain consultancy services in the context of the sampled proposals

Note: Proportions also include interest groups that did not use any consultancy services. Absolute number of service-using interest groups are written next to the bars. N = 278 (business associations = 92, firms = 125, non-business interest groups = 61).

This picture provides a stark contrast to the case of the United States where interest groups hiring consultants for access to policymakers plays a crucial role. The survey suggests that contrary to the case of the United States, the relationship between consultants and policymaker appears to be far less central to European consultancies’ business models.

Distinct patterns not only emerged with regard to the demand for services, but also in relation to clients. Business interest groups are the prevalent customers of consultancies: 34 per cent of all surveyed companies and 27 per cent of business associations respectively report that they rely on consultancy support when lobbying the Commission. In contrast, only 15 per cent of the remaining, non-business interest groups hire consultancies.

Firms and business associations appear to not only hire consultancies more often, but also buy more services. Surveyed firms buy on average 1.35 services, business associations 0.75, and non-business interest groups 0.41. Figure 1 suggests that for eight out of nine services, firms constitute the highest proportion of clients and business associations the second highest.

All of these results point towards the same question: why do business interest groups have a higher propensity to work with political consultancies? If your answer is money, you are – almost – spot on. By far the strongest impact on interest groups’ decision to hire consultancies is the availability of funds. But even with money accounted for, there is still a significant difference between non-business and business interest groups’ propensity to hire external lobbyists.

The likely explanation lies in the purpose lobbying activities serve these interest groups. Just as with any other organisation, interest groups’ ultimate goal is survival. Lobbying therefore serves the purpose of ensuring the acquisition of resources that guarantee this.

For membership-based interest groups such as business associations, this means that they need to retain and attract firms as members. The problem is, however, that firms can and will lobby on their own. This provides a strong contrast to non-business membership-based interest groups.

Professional associations, trade unions, and NGOs usually have individuals as members who are largely unaware about their organisations’ lobbying endeavours. In contrast, firms can effectively monitor their business associations’ lobbying activities. Business associations hire consultants to show that they are not merely active but rely on hired experts for a greater chance of success. This is particularly important because lobbying successes are often defined as maintaining the status quo, are rare events, and are generally hard to observe.

But even after hiring consultants, firms might still consider their interests not to be effectively represented by their business association. The positions of business associations often capture the lowest common denominator among their members, resulting in inadequate representation of the individual firm. And even if the firm gets what it wants, it might still be incentivised individually to seek private goods such as a narrow exemption from regulation from decision-makers.

The strong pull of such firm-specific benefits motivates them to rely on the most promising lobbying tools for interest representation. However, such moments of strong lobbying incentives appear to occur irregularly. After all, firms are not political actors in the narrow sense. Having the best ‘lobbying tools’ permanently on payroll for selective interest representation would constitute a disproportionate investment relative to the expected gains. This is the moment where firms decide to hire consultants.

These findings and explanations suggest some important take-home messages. Apart from the need for additional research to substantiate this narrative on business associations’ and firms’ consultancy hiring, they underline several important consequences of consultancy involvement for EU policymaking.

The role of political consultancies in EU policymaking is a double-edged sword. Hiring them contributes to the representativeness of associations by helping them maintain and increase membership bases. It also helps firms as non-political actors to participate in political processes. In both instances, consultancies can be seen as strengthening the input legitimacy of policies by improving or building up the interest representation capacities of political actors.

At the same time, we need to keep an eye out for distortions in interest representation caused by these hired guns. Political consultancies work predominantly for business interest groups. By amplifying primarily the already strong voice of business, consultants’ involvement fuels concerns about the participatory quality during policy formulation.

For more information, see the author’s accompanying article in European Union Politics

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics.

_________________________________

Oliver Huwyler – University of Basel

Oliver Huwyler – University of Basel

Oliver Huwyler is a PhD candidate in the Department of Political Science at the University of Basel, Switzerland. He is a member of the project Parliamentary Careers in Comparison (PCC) funded by the Swiss National Science Foundation (project number 162427).