National governments typically implement a range of policies to help integrate refugees into the labour market. Drawing on a new study, Vilde Hernes, Jacob Arendt, Pernilla Joona Andersson and Kristian Rose Tronstad show that policies focused on rapid self-sufficiency for newly arrived refugees may hamper the development of stable labour-market integration in the long-term. This effect is particularly prominent in the case of women.

Integrating refugees into the labour market has proven to be a challenge in all Western European countries, and there is a persistent employment gap between native-born citizens and refugees. To address these challenges, many governments design specific integration policies to deal with some of the obstacles that refugees encounter on their path to integration and employment.

However, systematic analyses of how these integration policies work are lacking. Insights into how different integration policies influence integration outcomes is highly relevant because an increasing number of European countries have focused on faster labour market entry and have introduced more restrictive requirements for access to social benefits and a secure legal status. This restrictive turn was particularly evident during and after the refugee crisis in 2015.

A Scandinavian comparative study

In a new study, we compare refugee employment levels in Denmark, Norway and Sweden during the first eight years spent by refugees in each country. All three countries offer full-time integration programmes in the first 2-3 years after settlement for adult refugees and their family members. The integration programmes combine three main integration measures: language and civic training, education and employment support.

We ask three questions. First, what is the difference in employment levels for refugees, overall and between men and women, across the three Scandinavian countries? Second, can different usages of integration measures explain the cross-national differences? And finally, what elements of the countries’ integration policies may explain such differences in integration measures?

Large cross-national differences in Scandinavian employment outcomes for refugees

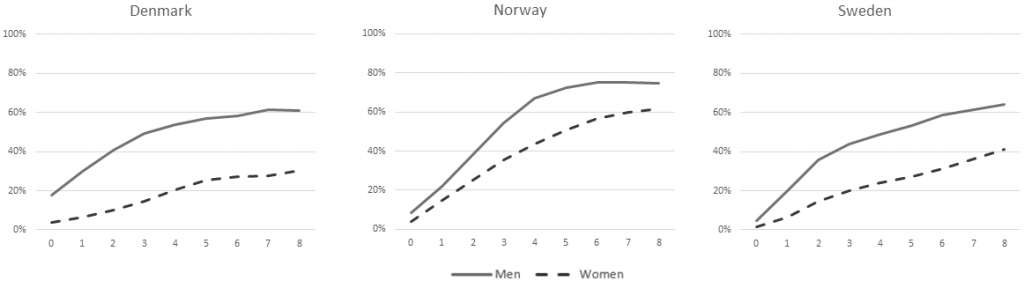

Our study reveals large cross-national differences concerning how employment evolves with time since settlement, holding individual characteristics and local labour market conditions constant. The cross-national employment differences are particularly large for refugee women. Denmark has the highest initial employment levels in the first years after settlement. However, Sweden and Norway catch up with or surpass Danish employment levels over time (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Estimated employment trajectories with years since settlement, by gender

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Figure 2 shows that despite the substantial employment gap between male and female refugees in all three countries, this gender gap is considerably lower in Norway than in Sweden or Denmark. The average estimated employment gaps between men and women during the first eight years in the country are 15 percentage points in Norway, 21 in Sweden and as much as 29 in Denmark.

Figure 2: Estimated employment trajectories for men and women with years since settlement, by country

Note: For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Different usage of education and subsidised employment may help explain cross-national employment differences

Denmark, Norway, and Sweden use the different integration measures in the integration programmes to a varying degree and these differences may help explain the diverging employment trajectories and gender gaps. We find that Denmark has very few refugees enrolled in regular education in the first three years after settlement compared with Sweden and Norway.

Although regular education has been shown to have a positive effect on employment opportunities, it naturally also implies a delayed transition to employment. Because regular education is a rarely used programme measure in Denmark, more participants are active job seekers, which could be a plausible explanation for Danish male participants’ higher employment rates in the initial years after settlement. The fact that few people enrol in education in the initial years could also provide an insight into why Denmark falls behind over time. Although Norway’s and Sweden’s investments in education in the initial years may have delayed labour market entry, this could be a plausible explanation for their more stable labour-market integration over time.

The combined usage of regular education and subsidised employment provides a plausible explanation for the different gender gaps in refugee employment across the countries. Norway, with the smallest gender gap, has an equal share of men and women who attend regular education and only a small difference between the number of men and women who attend subsidised employment. Sweden, which has a larger gender gap than Norway, also has equal shares of men and women who participate in regular education but has a substantially larger gender gap concerning the usage of subsidised employment. Denmark, which has the largest gender gap among the three countries, shows a substantial discrepancy between the genders of both subsidised employment and regular education.

Different emphasis on rapid self-sufficiency may explain different usage of integration measures

We conjecture that differences in the emphasis on rapid self-sufficiency in national integration policies may help explain the cross-national differences concerning usage of integration measures. When comparing national integration policies, Danish policies differ from those in Norway and Sweden concerning their larger focus on rapid self-sufficiency. This is not only evident in the integration programme but also in employment and self-sufficiency requirements for obtaining permanent residence and citizenship. With such requirements, individuals may be incentivised to gain (any kind of) employment as quickly as possible to obtain the required years of self-sufficiency because a long-term investment in qualifications could lead to a delay and uncertainty concerning their legal status and their right to remain in the country.

If there are no such conditional requirements, which was the case in Norway and Sweden during the period of analysis (before 2016), an individual has the leeway to choose different paths without risking potential eviction. This policy difference could be a plausible reason why more refugees in Denmark prioritise being employed fast instead of having a more long-term perspective by investing in education.

We also conjecture that differences in the social benefit systems in Sweden and Norway versus Denmark may provide one plausible explanation for the discrepancy in men’s and women’s participation in the integration measures. Norway and Sweden provide a social benefit for each participant, regardless of the financial situation of the entire family. This individual benefit is explicitly justified and promoted as a measure aimed at increasing the participation of female refugees in the integration programme.

In contrast, the Danish integration benefit is means-tested on the household level. This implies that female refugees will not have an individual financial incentive to participate in education or employment measures, nor is obliged to do so if they are supported by their husband or another family member. These differences in the right to receive financial benefits could constitute a plausible explanation for why fewer women participate in subsidised employment and regular education in Denmark compared with Norway and Sweden.

A trade-off between rapid self-sufficiency and long-term employment?

Our study indicates that there might be a dilemma between the goal of rapid self-sufficiency and long-term employment. The Danish focus on incentives for rapid self-sufficiency may lead to a faster transition to employment; however, this may be at the expense of a more long-term establishment in the labour market. In Sweden and Norway, it takes longer for participants to be employed, but the investment in language and education in the early years may contribute to a more robust labour-market establishment.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Flazingo Photos (CC BY-SA 2.0)