Several EU leaders have set their sights on curbing the power of big tech firms in Europe. Patrick Kaczmarczyk writes that it is unlikely the United States will accept this without the threat of retaliation. Due to its export-led model, the EU is vulnerable to such pressures. It is time for the EU to embrace a different theory and model of development, one that rethinks the idea of competition for its own sake.

With France and the Netherlands joining calls to curb the power of (mostly US-based) big tech firms in the European Union, it is likely that Washington will pressure Brussels not to impose any meaningful restrictions on its protégés. The threat to retaliate, for example via tariffs on EU imports, gives the US leverage, as the Eurozone – due to its dominance by Germany – adopts policies that make it reliant on external demand to grow.

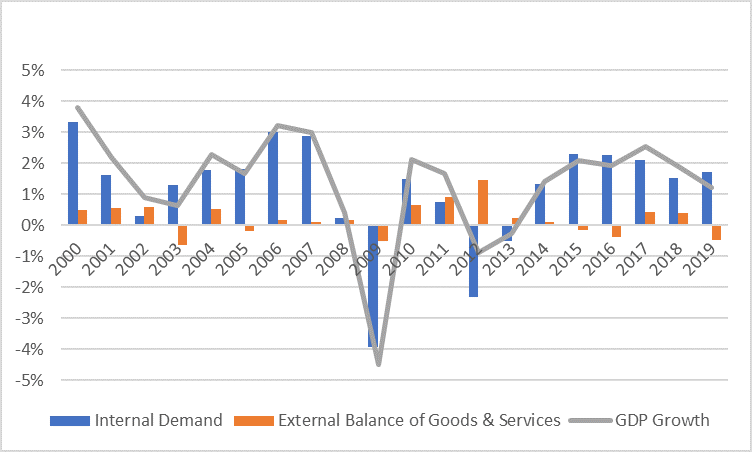

During and after the Eurozone crisis, the Exportweltmeister and some of its allies forced Southern European economies to follow its own export-models, with all the known consequences of high unemployment, low growth, and deflationary pressures. What the mercantilist alliance refuses to acknowledge is that the Eurozone, and, in a wider sense, the EU, are too large for such an endeavour to play out. The EU’s world export share stands at 15 per cent, and trying to increase it would either fail due to the retaliation of trade partners and/or a substantive currency appreciation. If it were to “succeed”, it would simply come at the expense of internal demand, which is a far more important driver of growth in the Eurozone (see Figure 1 below). The sad reality for mercantilist politics is that Europe (like the US) is a large and relatively closed bloc – a flourishing and dynamic economy requires an understanding of how to develop an economy from within.

Figure 1: Contributions to GDP growth in the Euro Area

Source: AMECO; author’s own calculations.

This is where we face an intellectual problem: how to endogenously develop an economy? The EU and its single market ontology rest on the idea that “competition” will do it for us. It adheres to the ordoliberal understanding that, if there is a framework for “competition” in place, development automatically follows. As its intellectual relative, i.e. neoclassical economics, it regards a world of perfect competition as a desirable ideal.

Yet, if we ever were to get there, we would find ourselves in a world of equilibrium, which means that everything is so optimised that, essentially, nothing happens. A theory that predicts a standstill as the end point seems to offer little to understand dynamic development as we have known it for the past 200 years. And indeed, technological progress, which is driving economic development, is exogenised in neoclassical growth models. In other words, it simply falls from heaven (or elsewhere) – without any idea of how or why it occurs.

A theory of dynamic development

Theoretically, therefore, neoclassical and ordoliberal theory and policy prescriptions are ill placed to give policymakers the tools to set up a framework in which development can take place. This is where one must turn to Joseph Schumpeter, who provided the most important dynamic theory of economic development. His insights suggest that there are different types of competition, some of which are conducive to development, others that are detrimental to it.

Contrary to the ordoliberal or neoclassical school, Schumpeter understands development not as an optimisation of the existing, but the creation of something new: The entrepreneur introduces a new combination of input factors (labour and capital) and obtains thereby a relative cost advantage vis-à-vis her/his competitors. This advantage can take either the form of a new product with monopolistic pricing power, or new, but more efficient methods of production. In either case, the pioneer has temporary unit labour cost advantages that s/he exploits in the market. Over time, when competitors begin to emulate the pioneer, the outcome is that overall productivity and living standards increase – what we generally refer to as development.

In a more stylised form, we can state that for the individual entrepreneur, who operates in a market in which all of her/his input prices are given, the only way to obtain an absolute advantage is to invest in new technologies to, ideally, combine the existing level of wages with higher productivity. In a world of international capital mobility and international differences in capital stocks (and therefore different levels of overall productivity), an additional option is to combine the existing level of productivity, i.e. a capital-intensive technology employed in advanced economies, with lower wages of developing economies. Yet, this would force the competition to equally outsource production, as otherwise, they would be pushed out of the market through lower market shares and/or lower margins.

Schumpeterian competition in the EU

The key to continuous development is to maintain a high and dynamic level of investments. There are several points to note here. The first one is that dynamic development requires low interest rates and fiat money creation, so that entrepreneurs take the risk to invest. Secondly, it requires imperfect competition, as only in such conditions can entrepreneurs ‘waste’ resources to experiment. Schumpeter was not per se against oligopolies or monopolies, as they can offer substantial advantages for development (such as synergies in the process of developing new technologies or economies of scale). Thirdly, as the renewal of the productive structure lies at the heart of Schumpeterian theory, he would reject the idea of a competition that is based merely on an optimisation of input factors.

Using existing methods of production merely more efficiently is not development. Yet, unfortunately, this is exactly the type of competition that is incentivised by the regulatory framework of the single market. It is obviously a lot easier – and a lot less risky – for firms to outsource the existing, capital-intensive method of production to where wages are lowest. The other method to gain competitiveness is via the suppression of wages (i.e. internal devaluation), which kills off internal demand without incentivising investments for the creation of something new. The situation in Europe is, of course, exacerbated by overly restrictive fiscal policies, which hamper public investments, which have been critical to technological progress.

So, what approach to competition should the EU adopt? Most importantly, it must put a coordination of wage policies centre stage. Fixed wage levels (according to each country’s overall productivity level), flexible profits – this should be the universal maxim. In the 1950s and 1960s, German policymakers referred to such wage policies as “Produktivitätspeitsche” (productivity whip), as fixed and in line with overall national productivity and the inflation target increasing wages push firms to produce more capital-intensively, i.e. increasing competitiveness through higher productivity. Firms which are successful in this endeavour have higher profits. Unsuccessful ones, however, fall off the cliff, as they cannot increase competitiveness by simply pushing down wages.

In an economic region of high wage disparities (as in the EU), where unit labour cost advantages can be obtained through merely outsourcing existing methods of production in combination with low wages, foreign direct investments (FDI) must be tied to conditionality, which forces foreign investors to increase their wages in the host economy in line with overall productivity gains and the inflation target there. The absolute advantages vis-à-vis competitors in the home economy would thus diminish over time. In the long run, the only way for the entrepreneur to be profitable would be through constant investments in new technologies – the Schumpeterian ideal.

In short, this approach to competition policy rewards pioneers and incentivises investments, while overall dynamic wage growth ensures that concomitant rationalisation does not generate unemployment but sustains a sufficient level of demand. The fact that such substantive policy interventions are a prerequisite for economic development may appear as a paradox to some. Yet, a continuation of the race-to-the-bottom does not lead anywhere but to stagnation. Equally, the reliance on some external “partner” for future development is, in particular in a post-Covid world, destined to fail. Considering what’s at stake, it may be worthwhile to be courageous enough to challenge some of the old static, equilibria-centric economic theories, which have nothing to say about dynamic development anyways.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image: Painting with Troika (1911) by Wassily Kandinsky. Original from The Art Institute of Chicago (Public Domain).