The European Central Bank has frequently used unconventional monetary policy approaches, such as large scale bond purchases, since the financial crisis. Armando Marozzi presents evidence of a new ‘doom-loop’ in Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union arising from these measures. He shows that once the ECB adopts unconventional monetary policy approaches, it tends to take stances that promote conservative fiscal policies among member states. This fiscal conservatism in turn produces lower GDP and inflation, increasing the need for further large scale bond purchases.

The notion of a ‘doom-loop’ usually refers to the relationship between banks and sovereigns in the euro area that arises when a large amount of government bonds on banks’ balance sheets erodes the value of bank equity as interest rates spike. In a recent paper, I extend this notion to unearth a new doom-loop between the institutional architecture of the European Central Bank (ECB), its unconventional monetary policy and the ECB’s ‘fiscal stance’.

While central bank independence has been praised as a ‘free lunch’ because it lowers inflation with no costs to output, I show that defending independence during a financial crisis in Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union (EMU) is macroeconomically costly. Since unconventional monetary policy exposes the ECB to the threat of fiscal dominance, the monetary authority of the euro area reacts by shifting its fiscal stance towards conservatism. In other words, to protect monetary dominance, the ECB demands governments constrain fiscal policies, thereby preventing them from free-riding on monetary measures. This, in turn, outweighs the positive effects of unconventional measures and results in a level of GDP and inflation that is lower than it would have been had the fiscal stance been constant. This new doom-loop is represented in Figure 1.

Figure 1: A new ‘doom-loop’ in Europe’s Economic and Monetary Union

Note: For more information, see the author’s accompanying paper.

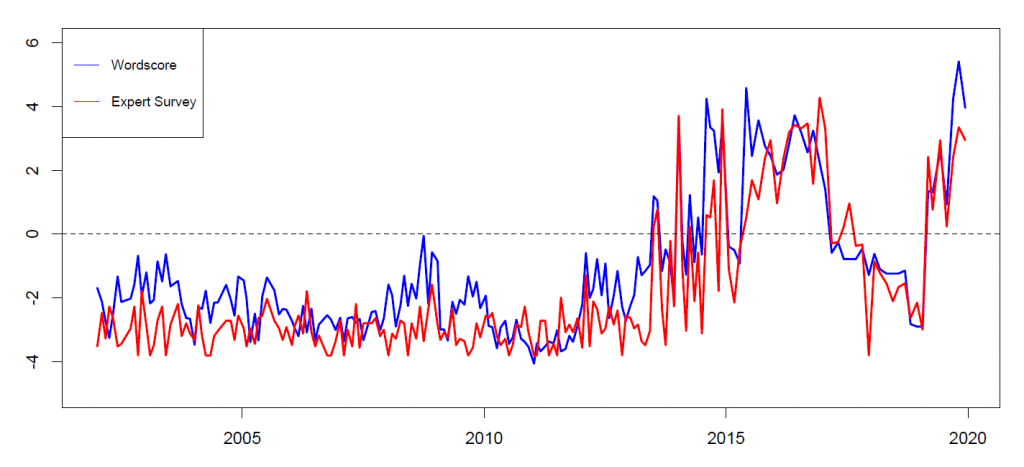

The underlying hypothesis here is that unconventional monetary policy may endogenously lead the ECB − to minimise the fiscal implications of those measures and, therefore, shield independence − to have a preference toward fiscal conservatism. To provide evidence in support, I first quantify the degree of fiscal policy accommodation of the ECB using the Wordscore approach (blue) and with an expert survey (red) in Figure 2 below; then, I study how this as well as other macro variables behave given an unconventional monetary policy shock. Figures 3 and 4 show some of these results.

Figure 2: Degree of fiscal policy accommodation

Note: Wordscore is a method of extracting policy positions from political texts. In using the approach to capture the degree of fiscal policy accommodation, I extract policy dimensions over normative fiscal policy paragraphs in the ECB’s introductory statements. I then validate the results of the model with an expert survey. The figure shows the estimated degree of fiscal policy accommodation for Wordscore (blue line) and the mean of the responses in the expert survey (red line). Above 0 indicates a fiscally dovish score (i.e. encouraging governments to increase the deficit to finance sizeable government spending to sustain aggregate demand), while below 0 indicates a fiscally hawkish one (i.e. encouraging governments to keep government budgets under control). The results of the expert survey were rescaled to make comparability easier.

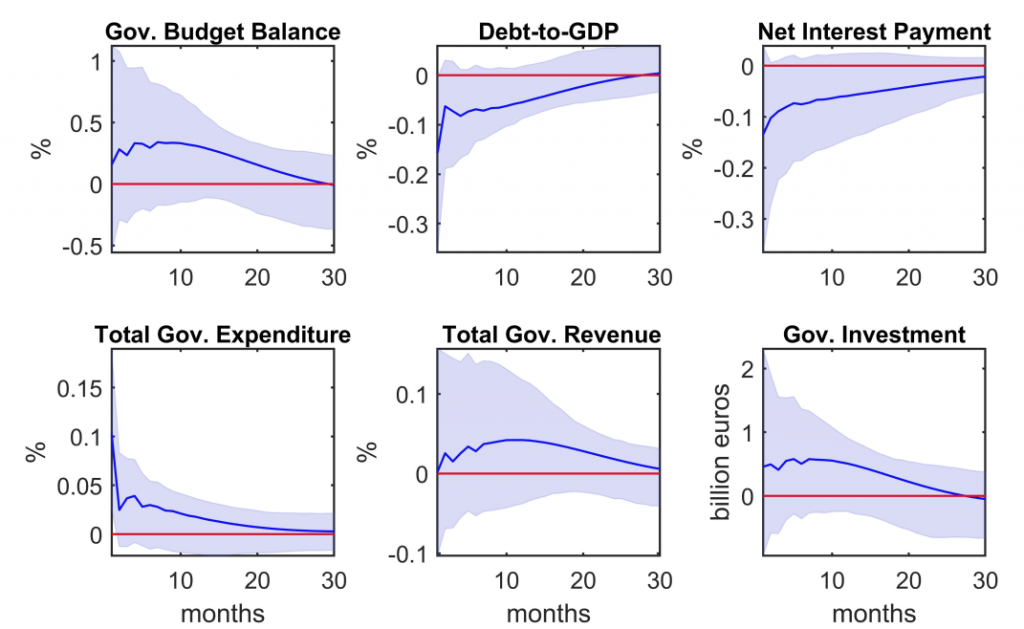

Figure 3 illustrates that government bond purchases have sizeable windfall gains for euro area countries, that is, the government budget improves, debt-to-GDP and net interest payments significantly decline and revenues increase. Besides, governments internalise the positive fiscal effects of monetary measures and increase government spending and investment, thereby proving that government spending responds countercyclically. This finding is important since the fiscal consequences of government bond purchases is what threatens the independence of the ECB via concerns about fiscal dominance.

Figure 3: Impulse response of fiscal variables to a large scale bond purchase shock

Note: Fiscal responses at the euro area level. Results are based on a factor augmented vector autoregressive (FAVAR) model identified with a proxy for Large-Scale Bond Purchases (LSBP) shocks. LSBP surprises are derived by exploiting the Euro Area Monetary Policy Event-Study Database (EA-MPD) by Altavilla et al. (2019) and originally adapting Swanson (2017)‘s methodology. The figure shows the response to a 0.25% decrease in the policy indicator due to an LSBP shock, with 90% bands displayed.

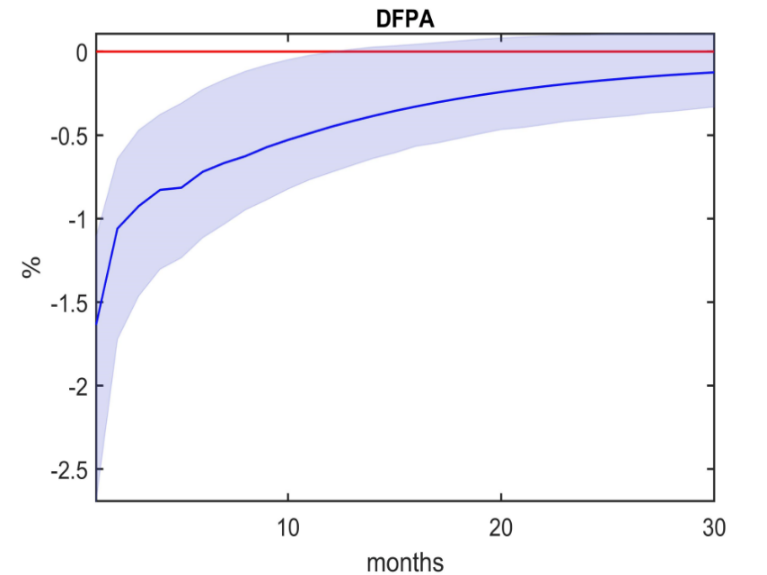

Figure 4, in contrast, displays the response of the communicated fiscal stance (degree of fiscal policy accommodation) to an expansionary bond-purchase surprise. The result supports the hypothesis according to which the ECB requires fiscal consolidation to come with large-scale purchases of government bonds. In fact, the model shows that the degree of fiscal policy accommodation plunges 1.6% on impact and remains significantly negative for 12 months after the shock. The ECB, therefore, calls on governments to constrain fiscal policies procyclically after an unconventional monetary easing.

Figure 4: Impulse response of degree of fiscal policy accommodation to a large scale bond purchase shock

Note: The figure shows the response to a 0.25% decrease in the policy indicator due to a large scale bond purchase shock, with 68% and 95% bands displayed.

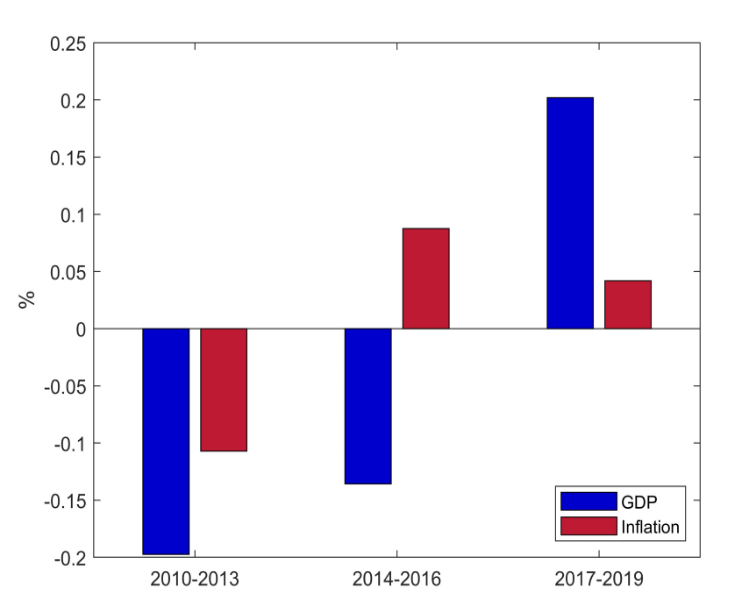

The last hypothesis is that the inverse relationship between the communicated ‘fiscal stance’ and unconventional measures found results in a level of GDP and inflation that would have been higher had the ECB kept its fiscal stance constant. Figure 5 shows the cumulative net effect of a hawkish shock in the communicated fiscal stance of the ECB over sub-periods of time. The bars below zero indicate that degree of fiscal policy accommodation surprises had a contractionary effect on the series and vice versa.

Between 2010 and 2013 – the period that covers the sovereign-debt crisis – GDP and inflation could have been higher by around 0.2% and 0.1% respectively. From 2014 to 2016, while the effect on GDP remained negative although somewhat reducing in magnitude (around -0.1%), the impact on inflation turned positive. Finally, over the period 2017-19, the counterfactual for GDP and inflation was positive for either variable. Hence, the contractionary effects due to fiscally conservative messages were stronger during the period in which the economy of the euro area needed to be stimulated the most.

Figure 5: Historical counterfactuals cumulated by period

Note: The figure shows the cumulative counterfactual for GDP and inflation in 2010-13, 2014-16 and 2017-19.

The main results of this analysis are as follows. First, when an expansionary, unconventional monetary policy shock is performed, the degree of fiscal policy accommodation decreases significantly: that is, the ECB becomes more fiscally conservative. Second, I find empirical evidence that sending fiscally hawkish messages is macroeconomically costly. In fact, GDP and inflation are higher in the scenario in which the degree of fiscal policy shock is turned off; in particular, during the sovereign-debt crisis. These results together prove the existence of a new ‘doom-loop’ between large-scale government bond purchases and the ECB’s degree of fiscal policy accommodation in the euro area.

Note: This article gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Central Bank (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)