Portugal is often cited as an exception to the trend of political upheaval and electoral instability that occurred across southern Europe following the financial crisis. Drawing on a new study, Elisabetta De Giorgi and José Santana-Pereira assess whether this perception holds across three key areas: government composition and stability, the country’s party system, and the political attitudes of citizens.

In the aftermath of the financial crisis, southern European countries have gone through a phase of electoral turmoil. This period has been characterised by new (challenger) parties entering parliament and even joining government coalitions, as well as long processes of government formation and, in some cases, the need to repeat elections.

In this context, Portugal has often been described as an exceptional case, marked by significant continuity with pre-crisis political dynamics. In a recent study, we explore the argument that Portugal presented distinct patterns vis-à-vis countries such as Greece, Italy and Spain during the country’s post-bailout period (2015-2019). We identify and explore three dimensions in which similar patterns can be seen in those three countries but not in Portugal: government composition and stability, the party system, and political attitudes.

Government composition and stability

In all four countries, governments resigned in 2011, but in Italy and Greece, this was followed by further government alterations, while in Spain and Portugal, the 2011 elections resulted in just one government, which remained in power for the entire legislature.

However, the Spanish party system began to change between 2014 and 2015 when Podemos and Ciudadanos started to pose a challenge to Spain’s traditional mainstream parties. The result was four general elections and three different cabinets between 2015 and 2019: an extraordinary pattern for a country known for its political stability since the 1980s. Thus, Greece, Italy and Spain experienced not only a large number of changes in government between 2015 and 2019, but also the rise of challenger parties capable of winning office or joining government coalitions.

In Portugal, the situation was quite different. The 2015 legislative election was neither an unequivocal victory for the incumbent centre right coalition, nor a clear success for its main opponent, the Socialist Party (PS). After a period of negotiation, for the first time in history three radical left parties – the Left Bloc (BE), Portuguese Communist Party (PCP) and the Greens (PEV) – gave external support to a Socialist minority government, which maintained power following the 2019 elections (though without the formal parliamentary arrangement with the radical left – which is known as geringonça or contraption). Portugal has therefore had a lower number of elections and cabinets in the 2015-19 period than its southern European counterparts.

The party system

A second striking feature of the Portuguese case is the party system’s resilience to the shocks created by the financial crisis. Neither of the three general elections that took place in the last decade caused an earthquake in the party system in terms of fragmentation or innovation. Electoral volatility between 2015 and 2019 was quite modest in Portugal, and considerably lower than that in previous legislative elections, as well as recent Italian, Greek and Spanish elections.

Party system innovation has also been remarkably absent over the last decade, particularly in comparison to the other three southern European countries. This did not change in the post-bailout period. Despite a slight increase in the effective number of electoral parties, no profound party system fragmentation has been witnessed, especially at the parliamentary level. Nevertheless, the 2019 election did witness the rise of two new right-wing parties, the radical right Chega, and the Liberal Initiative (IL), as well as increased support for the left-wing party Livre. All three parties entered parliament for the first time with one MP each.

Political attitudes

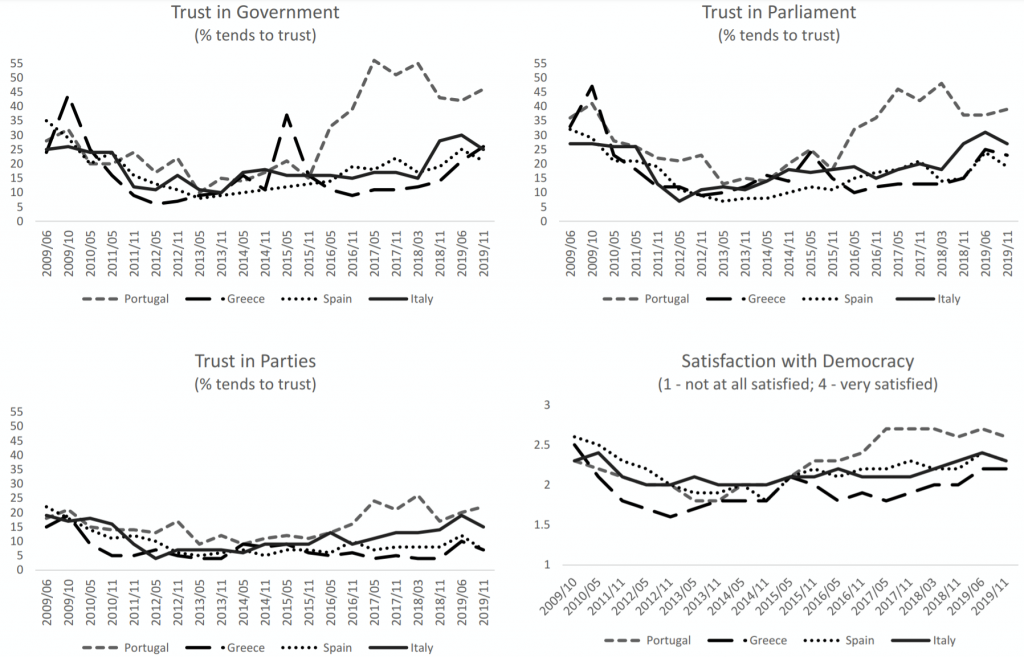

The Portuguese case also stands apart from the other southern European countries when it comes to satisfaction with democracy and trust in political institutions, which have both recovered quickly from 2015 onwards. According to Eurobarometer data, satisfaction with democracy in Portugal rose from 2.1 (on a scale from 1 ‘not satisfied at all’ to 4 ‘very satisfied’) in early 2015 to 2.7 in early 2017 and has not dropped since from the midpoint of the scale.

As Figure 1 shows, despite a trend towards convergence among the four countries from 2018 onwards, Portuguese citizens are still ahead of their southern European counterparts when it comes to satisfaction with democracy. Similar trends can be seen in terms of trust in government and parliament. The only partial exception to this trend concerns trust in political parties: while between 2017 and 2018 Portugal distanced itself from the other countries, values have slightly dropped in Portugal since then and improved in Italy, so Portugal does not stand out as sharply. Nevertheless, in November 2019 the proportion of Portuguese citizens who trusted political parties was three times higher than in Spain and Greece.

Figure 1: Levels of political trust and satisfaction with democracy in Greece, Italy, Portugal and Spain

Source: Authors’ elaboration of data from Eurobarometer.

Finally, during the last decade Portugal appeared immune to the rise of populism observed in other European democracies, including Greece, Italy and Spain. Yet our research indicates that there are no striking differences between Portuguese citizens and those in Greece and Italy when it comes to the presence of populist attitudes (Spain scores marginally lower on this measure, though still substantially above the midpoint of the scale).

Generally speaking, populist attitudes are extremely common in southern Europe. The exceptionalism of the Portuguese case is not found in relation to the prevalence of populist attitudes, which is high, but in the fact that until recently, those who hold populist attitudes had not found a party or political leader capable of expressing their views. The leader of Chega, André Ventura, now appears to be the political figure who was missing, but his arrival came much later than in the other countries.

On 24 January this year, Ventura received 12% of the vote in Portugal’s presidential election, finishing in third place. This most likely puts an end to Portuguese exceptionalism with respect to the absence of viable radical right populist actors. However, the election also revealed signs of continuity. Notably, candidates supported by or linked to the two mainstream parties reached almost 75% of the vote, in contrast to the 15% received by the new players. There was also confirmation of the Portuguese electorate’s tendency to abstain from elections, with participation levels reaching a new low of 39.5%, despite the presence of several candidates, both old and new, who were attempting to channel protest and discontent.

Still different?

All of the patterns we have illustrated above can be explained via several factors present in Portugal during the post-bailout period. These include a lack of sophisticated political entrepreneurship; the existence of parties already regarded as protest parties (BE and PCP), though without being viewed as anti-establishment; a trend towards abstention among Portuguese citizens; the stable relationship between the PS and the radical left; and fairly positive economic results.

Whether these exceptional trends are likely to last or not will depend on the country’s management of the Covid-19 pandemic and its social, economic and political consequences. Portuguese parties have proved to be resilient in both the bailout and post-bailout periods – it remains to be seen whether they will emerge unscathed from this new crisis.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in South European Society and Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council