One of the major stories from the 2020 Romanian election was the success of a new nationalist party, the Alliance for the Unity of Romanians, which surprised observers by winning over 9 per cent of the vote. Drawing on new data, Mihnea Stoica, Vladimir Cristea and André Krouwel explain how the party managed to build support so rapidly.

The most recent legislative elections held in Romania in December 2020 produced what was regarded by most political observers as a major surprise: a brand new, almost obscure, populist party, the Alliance for the Unity of Romanians – with an acronym that means ‘gold’ (AUR) – managed to gain over 9 per cent of the vote. The success of this ‘stealth party’ was missed by most pollsters and analysts. In the local elections that were held only two months before the legislative elections, the AUR only gained 1 per cent of the vote.

On top of that, several smaller parties fell victim to the 5% threshold for entering Parliament. The most remarkable losers were the Popular Movement Party (PMP) of former President Traian Băsescu and the PRO Romania Party of former Prime Minister Victor Ponta. The outcome also indicated a fragmented electorate, with no party managing to win more than 30 per cent of the vote. Finally, the incumbent government parties won enough seats to remain in office, which was also a departure from the typical ‘throwing-the-rascals-out’ mentality of voters in Romania.

The Romanian political landscape in the 2020 elections

As part of a recent project, a team of Romanian academics from Babeș-Bolyai University developed a so-called Vote Advice Application (VAA) for the 2020 Romanian elections. This online application allowed users to compare their opinions with those of the main parties. Users answered a set of 30 questions on political issues. Based on these answers, the VAA matched the user’s political preferences with party positions on the same issues.

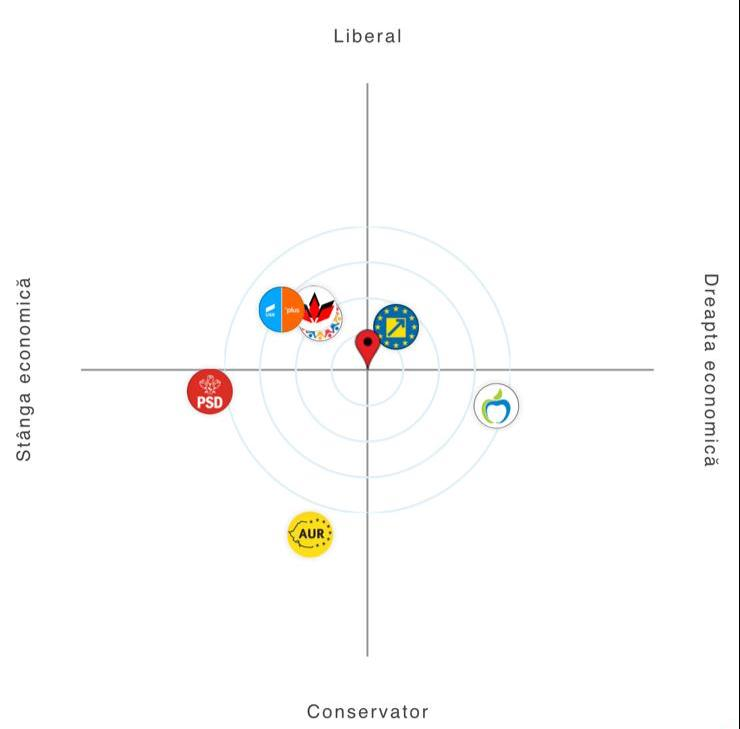

The parties were coded on the 30 topics according to their official positions, campaign documents and speeches by party leaders. The tool framed the positions of the parties on salient issues so as to give an ideological direction and determine their loading on one of the deeper cleavage dimensions that demarcate the Romanian political landscape, producing a multidimensional ‘map’ of party competition. Users could find where they were positioned in the political space, and how close or far they were from the main political parties. Figure 1 below shows this map of the Romanian political landscape.

Figure 1: Map of the Romanian political landscape

Note: The figure shows parties on a dimension between progressive (liberal) and conservative (conservator) values, and on a dimension between left (stânga) and right (dreapta) positions on the economy. The parties shown in the figure are the Social Democratic Party (PSD – left side of the figure), National Liberal Party (PNL – arrow logo, top right), 2020 USR-PLUS Alliance (blue/red split logo, top left), Alliance for the Unity of Romanians (AUR – bottom left), Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR – red logo, top left), Popular Movement Party (PMP – apple logo, right side), and PRO Romania (blue/red/yellow logo, top left).

For the 2020 elections, parties seemed to be mostly crowded on the left side of the political map. The Social Democratic Party (PSD) was the party positioned most to the left, but it was judged to be quite moderate on the progressive-conservative dimension. PRO Romania, which is a splinter party that broke off from the PSD, was also on the left, but with a slightly more progressive platform. The Democratic Alliance of Hungarians in Romania (UDMR), which mainly represents Romanian citizens with a Hungarian ethnic background, occupied a very similar position to PRO Romania.

The USR-PLUS alliance was the most progressive left-wing competitor. This alliance consists of the Save Romania Union (USR) and the Freedom, Unity and Solidarity Party (PLUS), two parties with fairly flexible ideological orientations. The Alliance for the Unity of Romanians ended up being the most conservative left-wing party. Voters that were located on the right side of the map were likely to end up closest to either the National Liberal Party (PNL) – a progressive and pro-European party which was in government at the time of the elections – or the PMP, which is a conservative party that shares some common ground with the Republican Party in the United States.

Stealth populism

By far the most unexpected outcome of the elections was the emergence of the AUR, which established itself as the fourth largest political force in the Romanian Parliament. In recent years, Romania has been one of the few countries in the European Union without a major nationalist-populist political force, following the decline of the Greater Romania Party (PRM) at the beginning of the 2010s.

What made the electoral result of the AUR particularly surprising for political observers and the general public alike is that the party did not even appear in the opinion polls conducted before the election. Polls only started to include it in the last days before the election, and even in these cases its score was massively underestimated. Yet while many Romanians heard about the AUR for the first time on the night of the elections as the exit-polls were announced, the party had been gradually growing their visibility throughout 2020, mostly through an efficient and well-targeted campaign on social media.

Most of the party’s main positions focus on Romanian nationalism, conservatism and protectionism. According to the party’s political programme, the four main pillars of the AUR’s ideology are “family, fatherland, faith and freedom”, and their campaign efforts commonly featured activism for the unification between Romania and Moldova, an opposition to progressive politics, criticism of foreign investment, and scepticism towards further European integration.

To sketch a profile of the AUR’s supporters, we use data collected during the election campaign – through the VAA as well as a post-election survey on a panel that is weighted to be representative for the total population. Respondents were asked who they voted for, but also to estimate the likelihood that they would ever vote for each of the other main parties competing in the election. This ‘propensity to vote’ (PTV) measure ranged from 0 (highly unlikely) to 10 (highly likely). We also asked voters to place themselves on a standard left-right scale, from 0 to 10.

If we regress vote propensities of the AUR against the self-declared left-right dimension we get no significant result. A regression of vote propensities for the party against the calculated left-right dimension based on all substantive statements on the economic dimension indicates that AUR voters tend to lean to the right in policy preferences. However, when we only take voters with a high propensity to vote for the party (greater than or equal to 6 on the scale), this effect is no longer significant.

Voters for the AUR are not very pronounced on the left-right dimension, but are very mixed both in self-declared ideological orientation as well as actual policy preferences. The appeal of the AUR is on the cultural dimension, where AUR voters are much more pronounced. In their conservative-progressive orientation, AUR voters are clearly conservative, for example opposing abortion rights, same-sex marriage and immigration. This finding matches with the position of the AUR in the Romanian political landscape, based on its political programme, where the party displays a mix of deeply conservative stances on the cultural dimension, but is moderately left-wing on the economic dimension (see Figure 1).

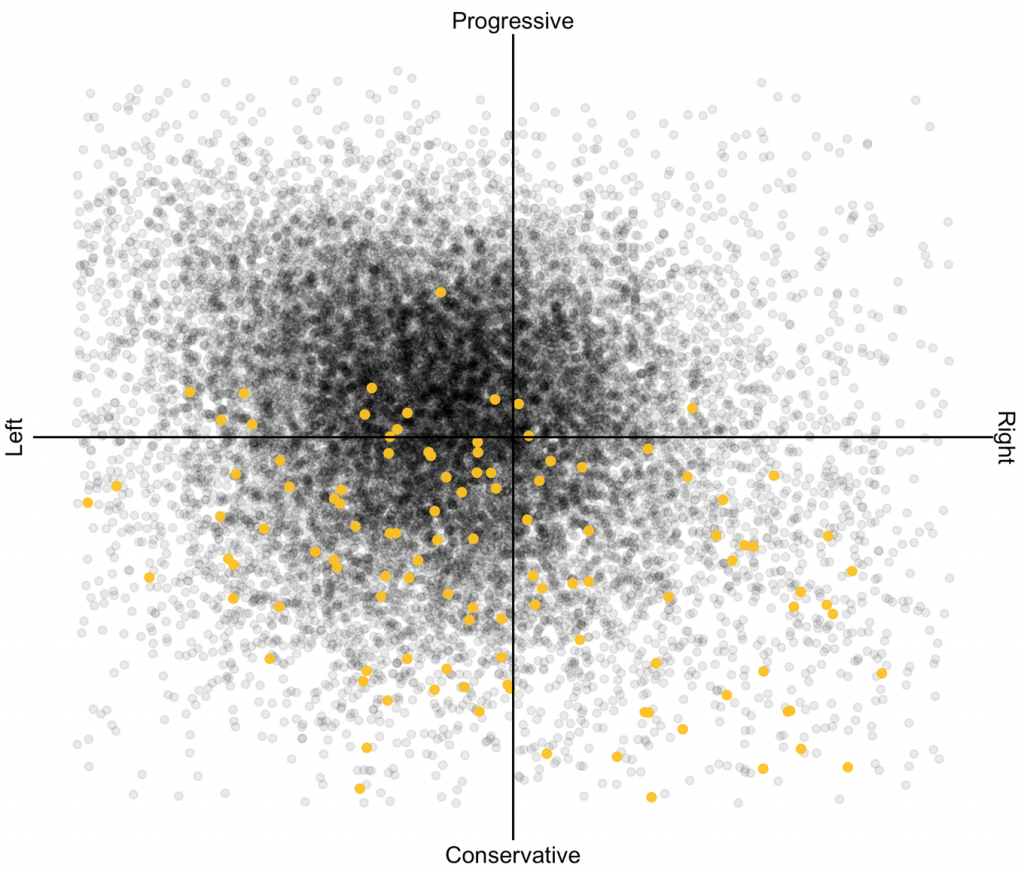

On economic issues, AUR voters seem to be highly diverse in terms of the left-right spectrum, and voter opinions on substantive issues show conflicting responses. For example, vote propensities for the AUR are essentially unrelated to responses to the statement that “the government should offer unemployed people more financial support”, yet they favour wealth redistribution from the rich to the poor. However, AUR supporters are also more likely to be opposed to government intervention in the economy and agree with decreases in government spending. When we plot such contradictory economic mindsets, we get the results shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Political positions of Romanian voters (AUR voters highlighted)

Note: The figure shows an estimate of the political positions of all voters contained in the sample, based on their responses to questions asked via the Vote Advice Application and a separate survey.

On European integration, AUR voters appear to be much more critical of the European Union than the general electorate. They are more likely to agree with the statement that “overall, EU member status is a bad thing for Romania” and that “European decision-makers are treating Romania like a colony”. They also tend to agree with the prioritisation of Romanian investors over foreign ones when awarding governmental aid and oppose the right of Hungarian-Romanians to education in their native language.

Covid-19, climate change, and corruption

Besides these conventional topics, a major reason for the success of the AUR’s campaign was the position many of the party’s prominent figures took on the Covid-19 pandemic. Throughout the outbreak, they criticised the government’s response, called for a loosening of lockdown measures, campaigned against face mask rules, played down the severity of the virus, organised gatherings and rallies without observing social distancing rules, and in some cases even promoted conspiracy theories about the virus or vaccines. In a country where 22% of the population does not want to take a Covid-19 vaccine and another 9% claims to be unlikely to take it, these actions gave the party widespread visibility and attracted sympathy from some parts of society.

These attitudes can also be seen in the data, as a preference for the AUR is positively associated with a belief that “the government should allow people to make their own decisions on how they want to protect themselves from the coronavirus during this pandemic”, and that “churches should remain open during the pandemic”. With respect to another topic where populist parties have a tendency to disagree with the expert consensus, climate change, the AUR fits the prevailing trend as their voters are more prone to believe that “the so-called climate crisis is an exaggeration” than the voters of other parties.

Another core message of the AUR campaign was its fight against government corruption and the political establishment. Analysing the data, it becomes clear how these messages have resonated so strongly, as AUR sympathisers appear to be less trusting of Romanian institutions than the voters of any other party. “The government is led by interest groups that aim to protect themselves” and “quite a lot of the people leading the government are corrupt” are two statements that they strongly resonated with, and AUR voters also seem to be the most pessimistic about the direction in which Romania is currently heading.

Sources of support

After the unexpected result in December, political analysts began to assess where AUR voters had switched their allegiances from. Our data reveals that there is no one party from which AUR has won its voters. Instead, their voters include people who voted for all of the other parties in 2016, as well as a very substantive proportion of people (as high as 50% of their electorate) who did not vote in 2016, were not allowed to vote because they were under the legal voting age, or voted for smaller fringe parties that did not enter the Parliament.

Demographically, our data shows that AUR voters are more likely to be male and have a lower level of education. Interestingly, compared to parties such as USR-PLUS or the PSD, whose electorates are very age-specific (youth in the case of the former, the elderly in the case of the latter), the AUR seems to attract voters of all ages. Nevertheless, the party is marginally more popular among younger people. These findings are consistent with previous results presented by CURS-Avangarde’s exit-poll.

While nationalist political mobilisation is no stranger to Romanian politics, as illustrated by the previous success of the Greater Romania Party, the rise of the AUR from an almost insignificant force to the fourth largest party in Parliament was undoubtedly surprising. Many Central and Eastern European countries have experienced an illiberal, populist and ultraconservative wave over recent years, so there are reasons to believe the AUR may be here to stay. However, whether the party will be able to consolidate their rather erratic and inconsistent voter base remains to be seen.

Note: This article is based on work conducted as part of the ‘Populism’s Roots: Economic and Cultural Explanations in Democracies of Europe’ (PRECEDE) project, financed by the Volkswagen Foundation. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Dennis Jarvis (CC BY-SA 2.0)