There is little question the EU’s enlargement process has stalled since the ‘big bang’ enlargement of 2004, but how has the discourse surrounding enlargement changed in European parliaments during this period? Drawing on a new study, Marie-Eve Bélanger and Frank Schimmelfennig find that enlargement discourse in European parliaments was significantly more restrictive during the 2010s, with the enlargement process losing salience and becoming increasingly culturally contested.

European Union enlargement has lost momentum. Hailed in the 1990s as the Union’s most effective foreign policy tool and credited with following a largely meritocratic process based on candidates’ liberal-democratic credentials, the successive waves of accession have turned into a trickle since the accession of Bulgaria and Romania in 2007.

In a new study, we examine how the enlargement discourses of parliaments at the European and national levels have developed since the ‘big bang’ of 2004. Has enlargement discourse become more negative and exclusionary? And if so, can we attribute this development to a partisan politicisation of EU enlargement or rather to democratic stagnation and backsliding?

The ‘rebordering’ of enlargement discourse

We conceive of ‘enlargement discourse’ as the aggregate patterns of the positions actors take, and the framing they use when discussing EU enlargement. We work with an original, manually coded dataset of parliamentary statements on membership in European organisations, covering the EP as well as the (lower houses) of France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Poland and the UK, thus including old and new member states, big and small member states and parliaments from the North, South and East of the EU.

We cover all enlargement-related debates in these parliaments from 2004 to 2017/18. Our basic unit of analysis is the enlargement claim, consisting of the position of an individual speaker regarding the admission of a specific country or a group of countries to the EU (support, conditional, oppose) – together with keywords justifying this position (frames).

We distinguish two broad types of framing. ‘Debordering’ frames refer to the openness of borders, their malleability and permeability and to meritocratic accession criteria such as democracy, the rule of law and compliance with EU conditionality. ‘Rebordering’ frames refer to the closure and rigidity of borders, to ‘communitarian’ or particularistic enlargement criteria such as geographic and cultural features that accession candidates cannot change, and to values related to demarcation such as identity, homogeneity and security.

We find that enlargement discourse has, indeed, become increasingly restrictive over the course of the 2010s. Enlargement has lost salience, especially in national parliaments of the member states. Positions on the accession of potential member states have turned more negative, and the framing of enlargement has become more ‘communitarian’.

Yet, there is significant variation among parliaments. The EP, the Bundestag and the Assemblée Nationale have similar moderately positive positions on enlargement, whereas the Greek parliament is considerably more sceptical. By contrast, the Hungarian, Polish and British parliaments are more positive about enlargement than the EP. The national discourses also show interesting variation between positions and frames. The French, Greek and Hungarian discourses are more framed towards rebordering than the British, EP, German and Polish discourses. Hungary is exceptional in combining some of the most pro-enlargement positions with the most communitarian framing.

The cultural politicisation of enlargement

In the next step, we analyse the factors that shape position-taking and framing. While controlling for the institutional and (supra)national particularities of the EP and the national parliaments, we distinguish two sets of factors: partisanship and candidate country characteristics. Strategic partisanship assumes that parties adapt their positions and frames depending on whether they are in government or in opposition. Opposition parties are assumed to be more negative about enlargement. By contrast, ideological partisanship assumes that parties’ positions and frames depend on their programmatic positions on the economic and cultural left-right axes of political conflict.

Plausible arguments can be made for both cultural and economic conflict on enlargement. From an economic perspective, parties on the economic right should welcome enlargement as it promotes market expansion; parties on the economic left should be opposed as enlargement potentially puts pressure on the wages and employment of low-skilled labour in the existing member states. From a cultural perspective, EU enlargement is a case of pan-European integration and transnational community building. Correspondingly, enlargement appeals to culturally progressive, internationalist parties. At the same time, enlargement is perceived as a threat by culturally conservative and nationalist parties.

Alternatively, or additionally, conflict about enlargement can be a function of the characteristics of the countries that seek membership. Thus, we also include measures of political, economic, religious and geographical distance between the country of origin of the speakers and the candidates they discuss.

Our analysis shows that parliamentary discourse on EU enlargement is characterised by cultural politicisation. Across parliaments, members from culturally conservative, nationalist parties are more likely to express a negative position and to use a ‘rebordering’ frame on enlargement. By contrast, we do not find a statistically significant effect of economic ideology on parties’ enlargement positions. These results hold regardless of the characteristics of individual accession countries.

Further examining particular features of candidate countries, we find that higher democratic quality and better governance are associated with more positive positions and open frames. This result supports the claims of the earlier enlargement literature regarding a norm-based and meritocratic process. At the same time, positions on more culturally (Muslim) and geographically distant countries are more negative than they should be if the discourse was strictly meritocratic. Finally, we observe an interaction effect between cultural party conflict and cultural distance between member and non-member states. Parties on the cultural right are more likely to express negative positions on enlargement when referring to Muslim candidates.

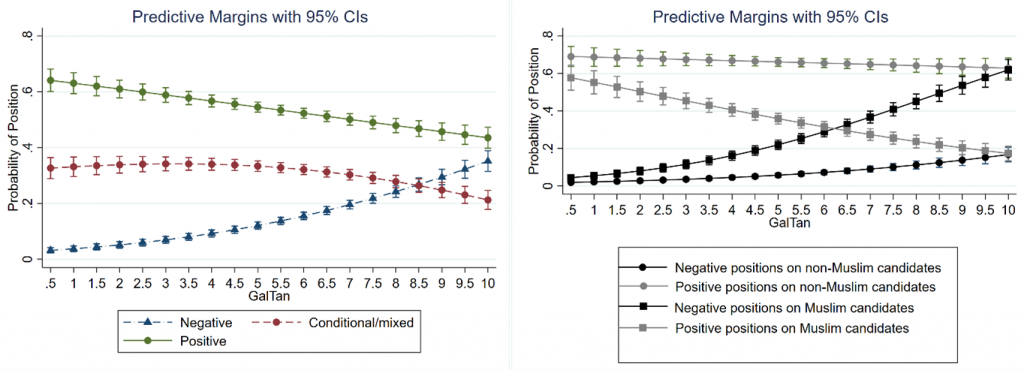

Figure 1: Cultural party conflict and positions on enlargement

Note: Left-hand panel: predictive margins of GalTan positions on the probability of negative, conditional and positive positions; right-hand panel: predictive margins of GalTan positions on negative and positive positions regarding Muslim and non-Muslim candidate countries.

For a visualization of the cultural politicisation of EU enlargement discourse, see the graphs in Figure 1. The left-hand panel shows that, as we move from the most socially liberal and internationalist to the most culturally conservative and nationalist party, the probability of a negative position increases from close to zero to over one third, while the probability of a positive position decreases from 64 to 44 percent. Whereas culturally liberal parliamentarians are more likely to express a positive position on enlargement than not, the reverse is true for culturally conservative parliamentarians.

The right-hand panel adds information on the interaction effect with religion. For the most culturally liberal parties, the religious culture of the accession country does not have a significant effect on the positions they express. As we move towards the right end of the spectrum, however, the gap widens. Among the most culturally conservative and nationalist parties, Muslim countries have a 60-percent probability of a negative position, as opposed to a less than 20-percent probability for non-Muslim countries – regardless of their democratic merits, economic situation or geographic location. Put differently, culturally liberal and conservative parties do not diverge much when they discuss Christian-majority countries, but hugely with regard to Muslim countries.

In sum, our results provide solid support for the politicisation of the parliamentary enlargement discourse in the EU. Ideological and strategic partisanship are robustly associated with both positions and frames in the debate. In particular, the enlargement discourse is shaped by the ideological divide between culturally conservative and liberal parties. That the religious identity of candidate countries reinforces this divide, supports the cultural interpretation. By contrast, the analysis does not confirm the expected association of party positions with economic ideology or candidate country wealth.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: © European Union 2014 – European Parliament (CC BY-NC-ND 2.0)