The economic disruption generated by Covid-19 has prompted many observers to ask whether globalisation has increased our vulnerability to economic shocks. Anna Maria Pinna and Luca Lodi examine what the future of trade and global value chains may look like once we emerge from the pandemic.

The Covid-19 pandemic arrived at a time when many citizens across the world were already harbouring doubts about the benefits of globalisation. Indeed, since the start of the financial crisis in 2007-8, we have been living in what Douglas Irwin has termed an era of ‘slowbalisation’, with global economic integration grinding to a halt. The rise of populism has rekindled interest in protectionist policies, while China and the United States, the world’s two largest economies, have been engaged in a trade war. Covid-19 threatens to push us further along this path.

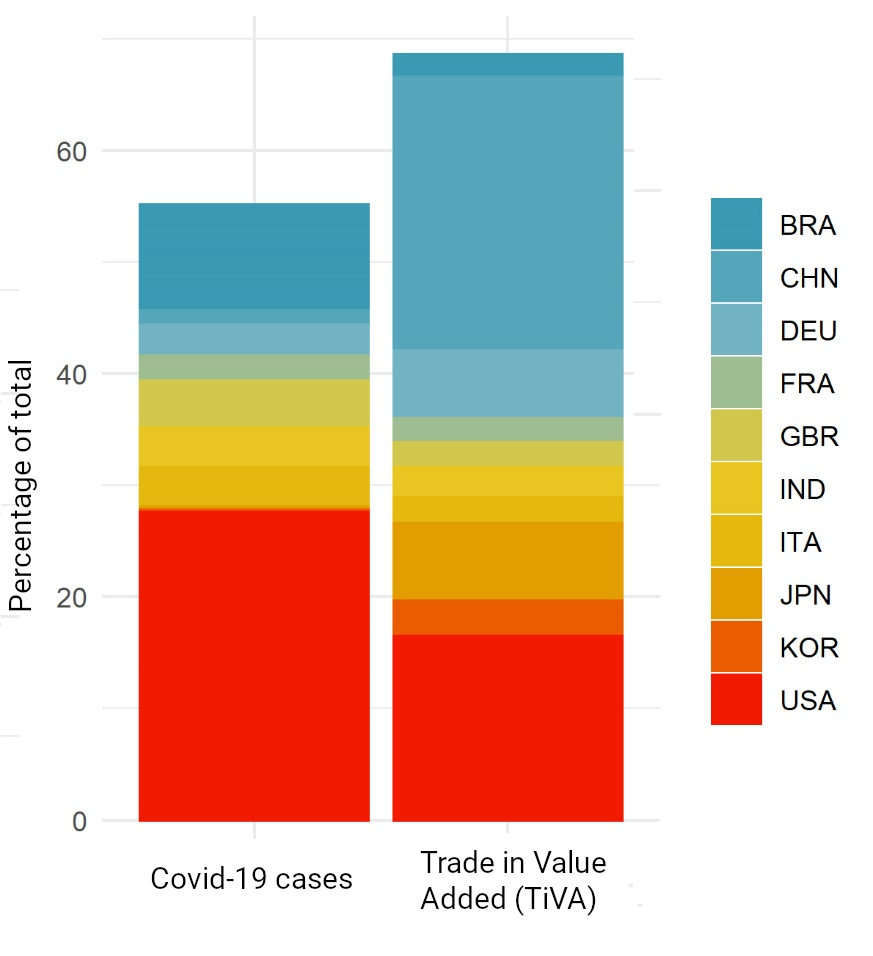

The economic impact of the pandemic has been particularly visible in the world’s largest economies. More than half of the confirmed cases in the initial wave of infections up to June 2020 were in the ten largest economies, which represent almost 70 per cent of global manufacturing production. While many Asian countries have since managed to control the virus to a greater extent than those in the West, these large economies still lie at the heart of the pandemic.

Figure 1: Percentage of global Covid-19 cases and value added by each country in the production of goods and services consumed worldwide

Note: Figure compiled by the authors using World Health Organization data on Covid-19 cases and the OECD’s Trade in Value Added (TiVA) figures from 2015. TiVA is a measure of the value added by each country in the production of goods and services that are consumed worldwide. The chart covers the period up until 6 June 2020.

The impact that the pandemic seems to have had up to now is far more severe than the recession brought on by the financial crisis. The IMF estimates that the contraction in global growth across 2020 was -3.5 per cent, with 90 per cent of countries having negative growth. Advanced economies were on average far more seriously damaged than emerging markets and developing countries.

The unique features of this crisis, which are already evident, can be attributed to an unprecedented combination of domestic and external shocks. These include the level of uncertainty injected into the system, chiefly linked to the health impact and efforts to combat the virus. This uncertainty was unparalleled when compared to previous events and much like the virus itself, it could not be constrained by national borders.

A second major feature is that many of the countries first affected by the spread of Covid-19 play a central role in global manufacturing. Aside from China, where the virus first emerged, France, Germany, Italy and the United States were also hit heavily in the first wave. This fed into a simultaneous supply and demand shock, magnified by the complex interconnections that exist between countries.

Third, the supply-side shock brought on by the pandemic has caused an unprecedented downturn in business activity. The rapid implementation of government interventions, such as household income support measures and the provision of credit for businesses, gives some indication of the scale of the shock experienced.

Finally, the economic impact of the pandemic may be self-reinforcing. For the first time since the Great Depression, advanced nations, emerging markets and developing economies have all entered a recession at the same time. Even many of those nations that have been less affected by the virus will eventually experience substantial economic damage due to their interconnections in the global market.

The future of trade and global value chains

All of this raises the question of how trade and global value chains may evolve in the post-pandemic world. Global supply chains are a central feature of today’s world economy. They have helped fuel prosperity, but we are now witnessing their potential to amplify shocks.

A supply disruption in one nation’s production network will show up as a reduction in exports in its trading partners. Alternatively, a drop in one nation’s income will reduce imports from its trading partners. The ripple effect produced by this interdependence has played a key role in shaping the economic impact of the pandemic. The critical issue moving forward is therefore the extent to which Covid-19 will lead to a major shift in the world’s economic architecture.

Given the global nature of the crisis, only coordinated action at the global level is likely to be able to mitigate the damage. Until now, most of the responses from governments have been focused on dealing with the problems experienced by their own citizens. Yet it is already apparent that the economic stimulus required to sustain demand will be more effective if countries coordinate their actions and avoid negatively impacting exchange rates.

Similarly, trade policy should ideally facilitate, rather than impede, national responses to the pandemic. Export restrictions on medical products are a costly undertaking: they increase international prices and have important distributional implications which affect both importing and exporting countries.

At the same time, the crisis presents an exceptional opportunity to examine the potential and limits of multilateral cooperation. Since the financial crisis, the importance of global value chains to total trade has decreased. There is no law that says globalisation must grow indefinitely, particularly when we consider that future technological developments are likely to ‘reshore’ production that has until now been located abroad.

What is clear, however, is that international institutions must help facilitate exports and target a reduction in tariffs, particularly for countries that are not involved in preferential trade agreements. They should also aim to boost the potential for plurilateral cooperation on technical regulations and related production processes. The extent to which this can be achieved will go some way toward shaping the future of trade and global value chains.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the International Spectator

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: william william on Unsplash