Since the EU referendum, the narrative of an inter-generational divide has emerged, with the country’s older pro-Leave generation thought to be at odds with a younger, pro-Remain generation. Rakib Ehsan investigated these intra-generational differences and suggests that failure to deliver Brexit may provide a boost for far-right organisations, but that a disruptive no-deal Brexit has the potential to inject considerable youthful energy into the Scottish independence movement.

Since the EU referendum, the narrative of an inter-generational divide has emerged, with the country’s older pro-Leave generation thought to be at odds with a younger, pro-Remain generation. Rakib Ehsan investigated these intra-generational differences and suggests that failure to deliver Brexit may provide a boost for far-right organisations, but that a disruptive no-deal Brexit has the potential to inject considerable youthful energy into the Scottish independence movement.

Brexit has dominated mainstream political discourse since the shock referendum result in June 2016. One of the dominant narratives which emerged from the referendum was the inter-generational divide, which is said to pit the pro-Leave older generation against a younger, pro-Remain cohort.

It is true that younger people were far more likely to vote to remain in the EU. This has meant that existing research and media coverage has focused on pro-Remain sentiments among young British people. However, there is a notable section of young British people who harbour Eurosceptic feelings – and our collective understanding of their socio-political attitudes is far from developed. Using a nationally representative, pre-referendum (May 2016) survey of 1,351 young British people aged 18-30, I explored differences between young pro-Leave people and their pro-Remain peers.

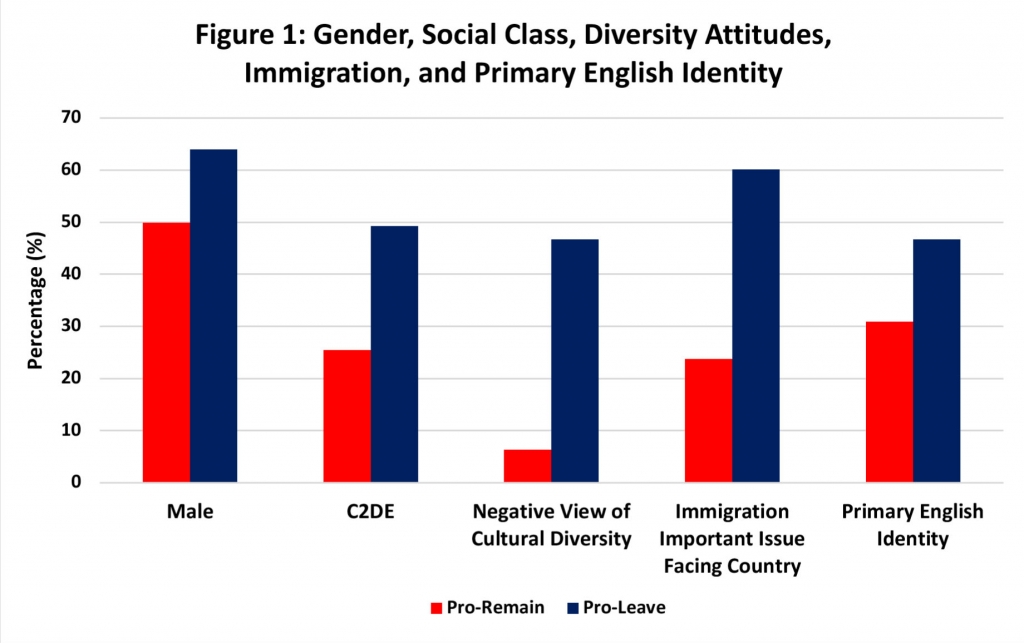

Figure 1 shows the percentage of the young pro-Leave and pro-Remain subgroups which fell into the following individual categories: being male; belonging to social classes C2DE; holding a negative view of cultural diversity; selecting immigration important issue facing the country; and reporting a primary English identity.

While the young pro-Remain subgroup was almost divided evenly in terms of gender composition (49.9% male; 50.1% female), 64% of the pro-Leave subgroup was male – a gender difference of 28 percentage points. In regard to class, just over 1 in 4 – 25.5% – of the pro-Remain subgroup fell into social classes C2DE. The corresponding figure for their pro-Leave peers was nearly half, at 49.3%.

There was a particularly sharp difference between the two subgroups when it came to their perspectives of the cultural diversity which has come to characterise modern British society. The young people in the survey were asked, “Do you think that having a wide variety of backgrounds and cultures is a positive or negative part of modern Britain?”. While only 6.4% of the pro-Remain subgroup reported a negative view of cultural diversity, this figure rises to 46.7% for their pro-Leave counterparts – a difference of over 40 percentage points.

Young British people who participated in the survey were also questioned on what they felt were the most important issues facing the country: “Which of the following do you think are the most important issues facing the country at this time? Please tick up to three.” Respondents were able to choose from the following policy areas: immigration and asylum; healthcare; economy; housing; Europe; environment; defence and terrorism; education; tax; crime; family life and childcare; pensions; and transport. They were also offered “none of these” and “don’t know” options. Out of the policy issues selected, the largest Leave–Remain gap was on the issue of immigration. Figure 1 shows that while 60.1% of young Leavers selected immigration as an important issue facing the country, only 23.8% of their pro-Remain peers followed suit.

In regard to primary (trans)national self-identification, the young British people surveyed were asked: “Which of the following best describes your identity?” For this part of the report’s analysis, five primary identities were considered: English, British, Scottish, Welsh, and European. Figure 1 shows that 30.9% of the pro-Remain subgroup reported a primary English identity, with the corresponding figure for their pro-Leave peers standing at 46.9%.

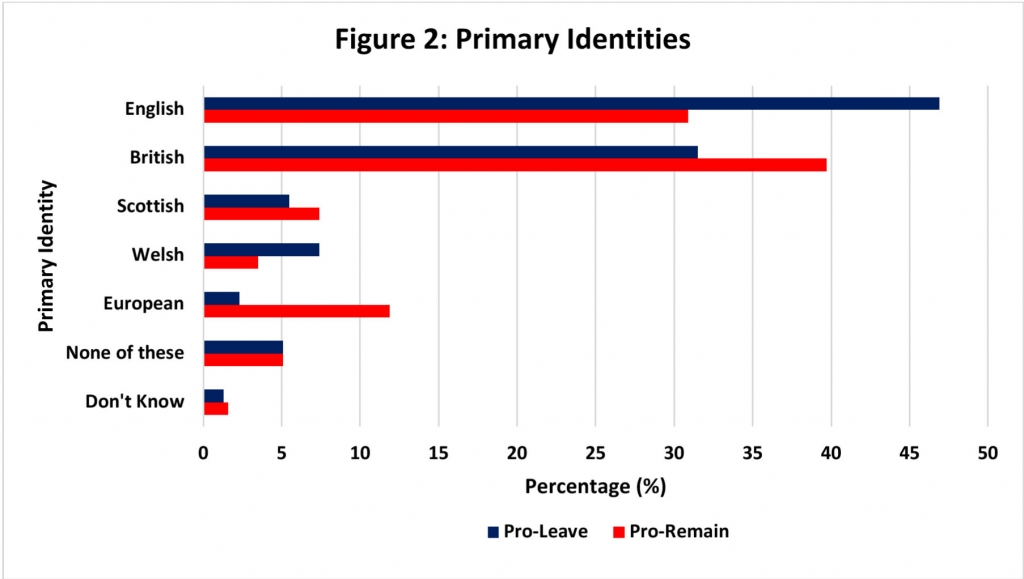

Building on the findings over primary identification, Figure 2 shows that the pro-Remain subgroup contained a higher concentration of young people who reported a primary Scottish identity, when compared to the pro-Leave subgroup (7.4% compared with 5.5%). However, the pattern is reversed for those who self-identified as Welsh, where the pro-Leave subgroup contained a larger proportion of young people who did this – in fact, more than double in terms of within-group percentage (7.4% compared with 3.5%).

Unsurprisingly, the pro-Leave subgroup included a far smaller proportion of young people who primarily identified as European when compared to the proportion within the pro-Remain subgroup (2.3% compared with 11.9%).

What the analysis shows is that there is no easy answer to questions over the possible political and social drawbacks associated with Brexit, as I explore further in a recent report for the Henry Jackson Society. Characteristics associated with pro-Leave sentiments among young people – male, lower socio-economic status, anxious over immigration, sceptical of cultural diversity, prevailing expressions of “Englishness” – also overlap with the profile of “target groups” for the recruitment and mobilisation processes of far-right organisations in the UK. Indeed, there is worrying evidence that “Brexit betrayal” rhetoric is being co-opted by far-right nationalist movements. A perceived failure to have delivered Brexit carries the risk of fuelling political disaffection among “at risk” groups traditionally associated with membership of far-right extremist groups.

On the flip side, the majority of Britain’s young people did vote to Remain, with positive views of immigration-induced cultural diversity appearing to be strongly related to pro-EU sentiments. A disruptive Conservative-led Brexit under Prime Minister Boris Johnson could also serve to intensify calls for Scottish independence among young Remainers living north of the border – adding considerable energy to renewed demands for a second referendum on Scotland’s possible separation from the UK. Indeed, a recent poll has shown that more Scottish people would prefer independence to remaining in the Union, with another survey showing that 60% of Scots believe support for Scottish independence would increase if the UK was to leave the EU on a no-deal basis. This is the dilemma that faces unionist politicians who are both pro-Leave (to the extent of supporting a no-deal Brexit) but also wish for Remain-voting Scotland to maintain its place in the UK.

Please read our comments policy before commenting.

Note: This article first appeared on our sister site, LSE Brexit. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Tom Donald via a CC-BY-NC-SA 2-0 licence

_________________________________

Rakib Ehsan – Henry Jackson Society

Rakib Ehsan – Henry Jackson Society

Rakib Ehsan is a Research Fellow at the Henry Jackson Society’s Centre on Social & Political Risk.