The 2021 Bulgarian election produced a fragmented result, with six different parties entering parliament. The country’s incumbent Prime Minister, Boyko Borisov, has already indicated that he will not put himself forward as a candidate to lead the next government. Ivaylo Dinev and Petar Bankov assess the options for a new coalition and what failure to reach an agreement would mean for the country’s future.

The election held in Bulgaria on 4 April produced a fragmented parliament with no clear winners, making government formation a challenging task. The centre-right Citizens for European Development of Bulgaria (GERB) and its leader, Boyko Borisov, have seen their grip on power weakened as a result of their handling of the pandemic and major anti-government protests that took place last year.

These developments have also marginalised the political influence of the other traditional parties in the Bulgarian political system. This opened the door to three new parties who entered parliament on the back of a wave of growing public dissatisfaction. Overall, the election results suggest that Bulgarian politics is currently experiencing a period of significant change.

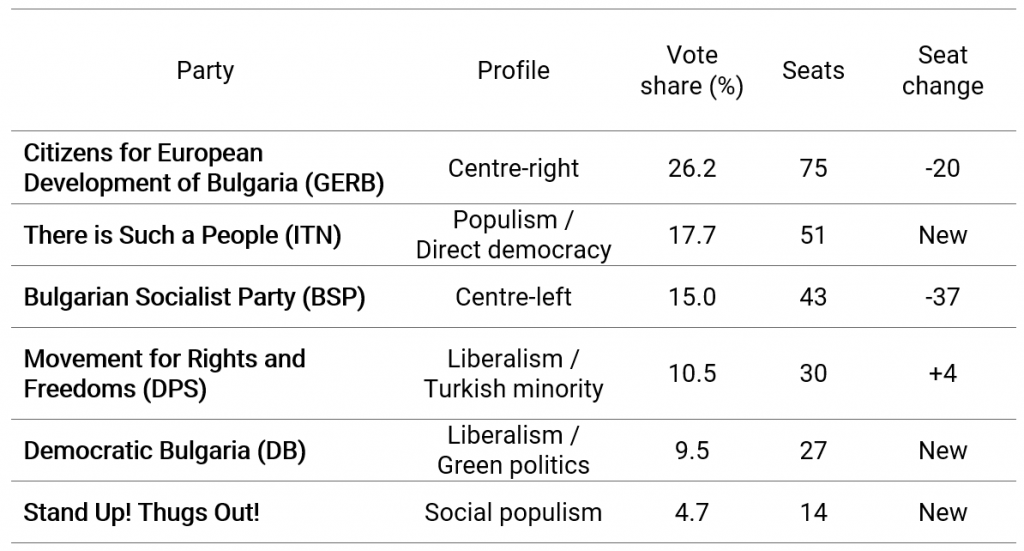

Table 1: Results of the 2021 Bulgarian parliamentary election

Source: Central Electoral Commission.

The results, shown in Table 1 above, partially reflect wider political trends present in Central and Eastern Europe. Much like in Romania and Croatia, where recent elections featured record low turnouts, there was a fall in participation, though the overall turnout of 50.6% was broadly similar to the level recorded in the 2013 and 2014 Bulgarian elections, despite the current pandemic.

With six parties entering parliament, the Bulgarian party system remains fragmented, a trend also noticeable in Latvia, Slovakia, and Slovenia. Both main parties in Bulgaria, the centre-right GERB and the centre-left Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), lost significant support, while the representative of the Turkish minority, the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS), failed to recover its losses from 2017. For the first time since 2005, the populist radical right will not be in parliament with the IMRO-Bulgarian National Movement (VMRO) barely missing the 4% threshold.

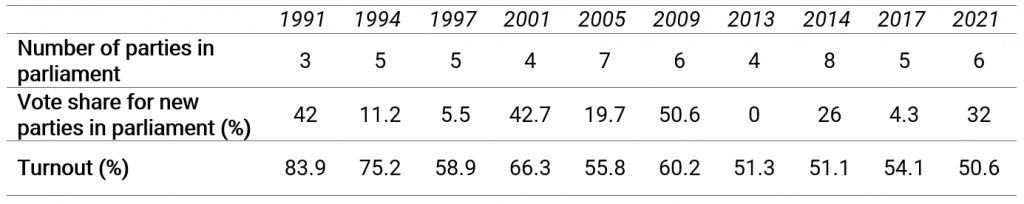

Table 2: Long-term dynamics in the Bulgarian political system (1991-2021)

Source: ParlGov database (Döring and Manow 2021) and Central Electoral Commission.

The three new parties joining the parliament include two populist parties, ‘There is Such a People’ (ITN) and ‘Stand Up! Thugs Out!’, as well as Democratic Bulgaria (DB), which is a coalition of liberal and green forces. Combined, they won around 32% of the vote.

At first glance, the current situation resembles the election in 2014, when a similar proportion of new actors appeared on the political arena, but without being able to challenge the hegemony of the traditional parties. This stands in contrast to the 2001 and 2009 elections, when new parties secured major breakthroughs (see Table 2 above). The 2021 election nevertheless indicates that the Bulgarian system is undergoing a major transformation.

Three important points show this development. First, the newly formed ITN pushed the BSP out of second place and is now the main opposition to GERB. The ITN managed to mobilise a third of diaspora voters and topped the youth vote. The party shares similarities to the Five Star Movement in Italy and its anti-establishment platform tapped into soft nationalist sentiments with prospects of developing a new niche within the Bulgarian party system. Another important change was Democratic Bulgaria topping the vote in the capital Sofia for the first time since GERB rose to power.

Second, the traditional centre-left BSP suffered a major electoral failure by dropping 13 points compared to the last election in 2017. This is the worst result in its post-socialist history and a particularly dramatic one as it comes following a period in opposition. The BSP failed to mobilise even its core voters, while prolonged infighting within the top ranks of the party and disillusionment with Korneliya Ninova’s heavy-handed leadership spell future trouble.

Finally, the DPS lost its king-maker role, having been pushed into fourth place by ITN and the BSP. This might potentially open some space in the Bulgarian political system for new stable coalitions that can enter office without relying on the DPS’s tacit support – a feature of Bulgarian politics that has helped entrench political horse trading, patronage, and corruption.

A challenging, but not impossible coalition formation process

Generally, all of the parties in parliament will need to be much more innovative to form a stable coalition government. After the wave of anti-government protests and increasing public tensions, GERB faces a stronger and less compromising opposition than before, revealed in the first parliamentary session when all parties but GERB elected the parliament speaker. So far, GERB is in firm political isolation. Borisov has sought a breakthrough by proposing a more acceptable candidate for Prime Minister, Daniel Mitov, instead of himself. Nevertheless, the party has not done itself many favours. Borisov has avoided attending the parliament to face parliamentary questions, while the outgoing government also disbanded the National Operative Staff (NOS), which was handling the country’s pandemic response, in a surprise move.

In such circumstances, the task of forming a government lies with the political opposition, particularly ITN as the second-placed party. The party has avoided making clear statements beyond its refusal to collaborate with the traditional parties (GERB, BSP, DPS). The other two new parties, ‘Stand Up! Thugs Out!’ and Democratic Bulgaria, support entering into a government coalition with ITN.

The success of such a coalition would depend on three factors. The first would be finding additional support. The three parties are 29 seats short of a parliamentary majority, so they require the support of either the BSP or DPS. Both parties have already declared their willingness to support such a coalition, so the question is whether the three new parties would accept the potential electoral costs and policy compromises of the collaboration. ‘Stand Up! Thugs Out!’ is already split on this question.

The second factor would be reaching an agreement over the immediate government priorities. All three new parties are in favour of a fundamental reform of the electoral code, improved measures against the pandemic, a thorough inquiry concerning the past government, and reversal of key government policies related to the functioning of the judicial system. The question here is which of these policies would be prioritised as all three new parties have not denied the possibility of early elections if the deadlock remains. Therefore, time seems scarce.

Third, there is the question of how much appetite there is for new elections in the autumn. While it is unclear who would benefit from returning to the polls, a second election may have a significant negative impact on the country. After prolonged discussions with social stakeholders, the government has not passed its recovery plan concerning the €12.3 billion the country has been allocated from the European Recovery Fund. Additionally, Bulgaria still lacks a strategy on how to spend the €16.7 billion allocated from the 2021-2027 Multiannual Financial Framework. Now the new parliament and potential government have the difficult task of revising and passing the plan in a short timeframe if they want to avoid losing access to these funds.

No solution for rising social inequality

Such a financial stimulus is badly needed. The pandemic has hit the people of Bulgaria and their health system hard, while the overall socio-economic situation is deteriorating. According to IMF data, the Bulgarian economy contracted by 4.2% in 2020 and exports fell by 11.3%, while investment was down by 5.1%. GERB’s conservative fiscal policy has been maintained during the pandemic, with Bulgaria ranking last in the EU in spending on anti-crisis measures at only 6.7% of GDP compared to the 14.3% EU average.

Moreover, the country lags behind in absorption of financial resources from the SURE fund to protect jobs and incomes affected by the pandemic. Thus, it is not surprising that Bulgaria has once again found itself at the top of Eurostat’s measurement of income inequality in the EU. Bulgaria continues to be the country with the lowest hourly labour cost in the EU and has extremely high levels of material deprivation. A recent report on the cost of living in Bulgaria shows that six out of ten households are unable to meet the level of subsistence, which equates to around €325 per household member per month.

In this socio-economic context, the fragmentation of the political system and growing political instability may foreshadow a deeper long-term crisis. Currently, none of the six parties entering the new parliament have committed to a fundamental change of Bulgaria’s socio-economic system. A recent analysis of the political manifestos of the leading political parties showed a strong imbalance towards economically right-wing measures and positions, while more socially-oriented alternatives are almost absent.

Internationally, the situation spells trouble as failing to use EU funding properly in the coming months will stall the country’s economic recovery while limiting its efforts to catch up with the other EU member states. Meanwhile, the absence of any nationalist parties in parliament may mean a potential moderation towards the question of the EU accession of North Macedonia, as well as a firmer commitment towards Bulgaria’s Euroatlantic orientation. Whether the political fragmentation will allow Bulgaria to improve its quality of democracy remains unclear.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council