The Covid-19 pandemic has had a disproportionate impact on those living in nursing homes. Joan Costa-Font, Sergi Jimenez-Martin and Analia Viola find evidence that regional variation in nursing home fatalities during the first wave of the outbreak in Spain was associated with proxies of underfunding. Other explanations include coordination failures between health and long-term care, and between central and regional governments.

In Spain, 87% of Covid-19 deaths have been among individuals aged 70 years and above. A large number of fatalities have occurred in nursing homes. Around 13% of all nursing home residents in Spain died from the virus in the first wave of the pandemic. This figure rises to 22% of nursing home residents over the age of 80.

Certainly, not all countries were equally prepared to face the healthcare consequences of the first wave of the pandemic. Before the pandemic, hospital admissions were slower among nursing home residents than community equivalent populations. Furthermore, community infections in Spain do not correlate with nursing home infections. What, therefore, can explain nursing home fatalities?

Austerity and underfunding

Spain, alongside other Southern European countries, was heavily exposed to austerity cuts in the 2008-13 period, which resulted in a significant reduction in the level of long-term care funding available. This may have magnified the effects of the pandemic in nursing homes.

A common reaction to underfunding has been to reduce the hiring of permanent staff. Underfunded nursing homes might therefore lack sufficient human resources to perform their duties at the expected level. Underfunding has also led to an increase in patient numbers at nursing homes, which made it challenging for high occupancy facilities to find rooms available for social distancing.

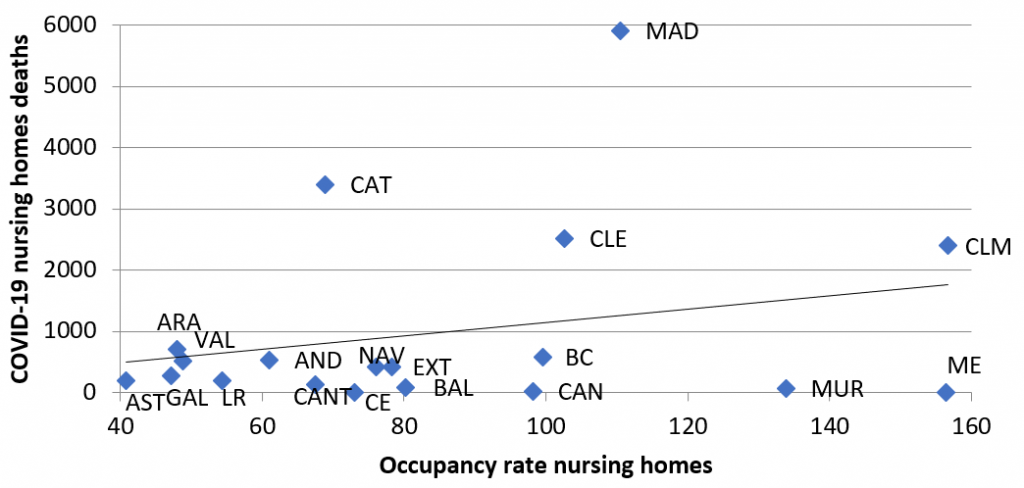

One way to test this ‘underfunding hypothesis’ with the limited data available is to examine the association between proxy measures of nursing home underfunding, including understaffing (staff to places ratio) and nursing home fatalities (relative to excess deaths). Other alternative proxies include the role of average nursing home size (larger nursing homes might not guarantee access to protective equipment) and nursing home occupancy rate (as occupancy plays a role in limiting the availability of spare rooms for self-isolation). Figure 1 below shows some evidence of the regional variation in Covid-19 fatalities as a share of excess deaths and nursing home occupancy rate.

Figure 1: Average occupancy rates and Covid-19 nursing home deaths by Spanish region

Note: Occupancy rate refers to the number of users per number of beds. Data of users (IMSERSO): Aragón, Canarias and Extremadura, data from 2016. Galicia, data from 2017. Rest of regions 2018. Source: RTVE and IMSERSO.

In a recent study, we find evidence of an association between nursing home deaths relative to excess deaths, whereby larger-sized nursing homes exhibit higher fatalities relative to excess deaths. Similarly, we find a reduction in relative fatalities per additional staff per place in a nursing home. However, these estimates come from a small number of observations and report an adjusted association that cannot be interpreted as causal.

Coordination failures

Other explanations include limited investment and coordination of health and long-term care, giving rise to the well-known ‘bed blocking’ problem, which is deemed to be the cause of a significant share of excessive hospital care use. Health and long-term care services in Spain have traditionally been subject to several types of ‘coordination failures’ both between health and social care services, and between different levels of government. Coordination failures help explain why on average most regions took between 26 and 31 days to report a case.

Coordination plans for health and social care have been limited to a few regions. Only 8 of 17 regions in Spain had developed health and social care coordination plans at the time of the pandemic. The Spanish government made coordination failures after centralising health care stewardship whilst social care remains uncoordinated in the hands of regional authorities. Finally, in some regions, older age patients were refused emergency health care from major hospitals, with clinical guidelines explicitly stating older patients residing in nursing homes should not be admitted.

Moving forward

Underinvestment in nursing home care, specifically in regions exhibiting lower staff to nursing home places, is correlated with a higher nursing home fatality rate relative to excess deaths. Coordination failures have made things worse. A key lesson is that in evaluating long-term care programmes, one needs to bear in mind the externalities that they engender in other areas of economic activity such as health care, especially during a pandemic.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of Aging and Health

Note: This article first appeared at our sister site, LSE Business Review. It gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: eberhard grossgasteiger on Unsplash