The Covid-19 vaccine rollout in some EU member states may interact with the effective use of grants and soft loans from the EU’s 672.5 billion euro pandemic recovery fund. Renato Giacon and Corrado Macchiarelli write that with national spending plans for the recovery fund still awaiting approval, the next challenge for policy-makers will be to ensure that funds are released as economies reopen. Special attention will need to be paid to Central and Eastern Europe, where some countries are lagging behind in their vaccine rollout and preparation for their use of the recovery funds. This is likely to be an important test for the EU’s institutions and will help determine the stability of the European project.

Almost a year since the French president Emmanuel Macron and German chancellor Angela Merkel threw their weight behind the idea of the EU Recovery Fund, and nine months after EU leaders agreed to the 750 billion euro (in 2018 prices) Next Generation EU Programme, many EU governments have started to formally submit their national Recovery and Resilience (RR) Plans to the European Commission, with the euro area’s “big four” – Germany, France, Italy and Spain – having all presented their plans well ahead of the Friday 30 April soft submission deadline.

Four out of the five countries previously at the centre stage of the European sovereign debt crisis – Italy, Spain, Greece and Portugal – have so far emerged in a rather positive light with most of their plans receiving initial praise from the European Commission for their high-quality and serious level of ambition in terms of investments and policy reforms. The process will still be relatively long, as the plans will be vetted by both the European Commission and EU member states in the Council, with the earliest date for disbursement not expected to be before the second half of July for most member states. Yet, previous experiences and the ability to implement reforms in front of market and institutional creditors seems to have served many of the Southern European economies well in taking seriously the Commission’s requests to allocate EU funding efficiently.

While the approval process of the EU funds might appear cumbersome, especially when compared to the US fiscal package approved in the early days of Joe Biden’s presidency in March, such protracted planning could well represent serendipitous timing which could match the longer than expected European pandemic recession. With most EU countries experiencing a technical recession between the fourth quarter of 2020 and the first quarter of 2021, the summer deadline could mean EU Recovery and Resilience Facility (RRF) disbursements might coincide with the reopening of some EU economies. Overall, this could play out well, as rebounding economies could get a breath of fresh air from EU funds just when vaccinations are ramped-up in meaningful proportions, allowing for an efficient and timely use of the European fiscal resources. These interactions might contribute to building-up private investors’ trust in the EU and national governments’ institutional efficiency and help the return of free and unfettered mobility of people, especially for those EU member states most dependent on tourism receipts.

The recovery fund’s initial disbursements

The road ahead is still long with several key milestones creating potential hurdles for the rollout of the Recovery and Resilience Facility funds. First, eight EU countries – Austria, Estonia, Finland, Hungary, Ireland, the Netherlands, Poland and Romania – have yet to ratify the EU’s so-called ‘Own Resources Decision’ (ORD). The ORD’s entry into force requires approval by all EU member states according to their constitutional requirements to make it possible for the European Commission to be legally authorised to borrow up to 800 billion euros (in current prices) on capital markets until the end of 2026.

Second, there is the submission and approval of Recovery and Resilience Plans. By mid-May 2021, 17 EU governments had submitted their investment and reform proposals to access their allocation of funds. This represents around 88% of the available Recovery and Resilience Facility grants as most EU countries receiving the largest amounts of grants have already applied, apart from Romania. The European Commission will take two months to vet the plans, particularly as they will need to fulfil targets for green and digital investments, as well as show commitment to a sufficient number of structural reforms.

Finally, there is peer scrutiny. Once the Commission approves the Recovery and Resilience Plans, it will make a funding proposal to the Council; national governments will then have up to one month to pass judgement on their peers, with political pressure likely to build especially on the net recipients. Therefore, it might be late in the summer before the money starts to effectively flow into national economies.

However, the large amounts involved, and previous experiences with inefficient absorption of EU funding in the member states, justifies the Commission’s insistence on structural and long-term targets, such as productive digital and green investments, which extend to the adoption of economic and administrative reforms. In fact, as the majority of EU member states can already borrow at historically low rates on capital markets, the goal of Next Generation EU appears to be increasingly more focused on raising potential growth, improving long-term fiscal sustainability, and helping economic convergence across the EU/euro area, rather than achieving short-term fiscal stabilisation. This is particularly significant in helping the discussions on debt mutualisation in the euro-area, by moving the goalposts from legacy debt to new investment.

The Commission has foreseen that an initial fiscal transfer of up to 13% of the entire Recovery and Resilience Facility allocation can be disbursed to each member state immediately in the form of non-refundable grants, after the Commission and Council formally validate and approve Recovery and Resilience Plans. This means that, in order to remain within the recovery fund’s pre-financing financial envelope, only a limited number of countries will be given the final go-ahead between the second half of July and September 2021, with Greece widely expected to be the frontrunner.

As a matter of fact, the Commission could find it difficult to transfer the first tranche of the funds to all member states on schedule, as most of the plans are expected to be approved simultaneously. There will be limited capacity for the Commission to borrow from the markets the roughly 45 billion euros that would be needed to cover the 13% of pre-financing for the Recovery and Resilience Facility non-refundable grants. Based on the available estimates, the Commission could raise only between 15 and 20 billion euros a month to finance the Recovery and Resilience Facility and it is increasingly likely that a larger second batch of EU member states might be left high and dry until the end of the year, experiencing the double whammy of delayed vaccination supplies and European fiscal resources.

Serendipity or a missed chance?

After a first, deep, recession in the first half of 2020, the National Institute of Economic and Social Research (NIESR) figures recently published show that the euro area is not forecast to return to pre-pandemic levels until late 2022. The weight of a third wave of infections and supply-side problems in accessing the vaccines have left most EU economies lagging behind some large trading partners, such as China and the US.

However, leading indicators, such as IHS Markit’s final PMI readings for the euro area, give hope the current recession may not extend beyond the current quarter, with the PMI index rising to the highest level since 1997, climbing to 62.9 in April 2021. The accelerating pace of vaccinations across Europe and signs that the last wave of Covid-19 infections appears to have peaked already are fuelling hopes of a demand-driven economic rebound in the second quarter of this year and especially after the summer, when the initial Recovery and Resilience Facility funds are expected to be disbursed for some countries.

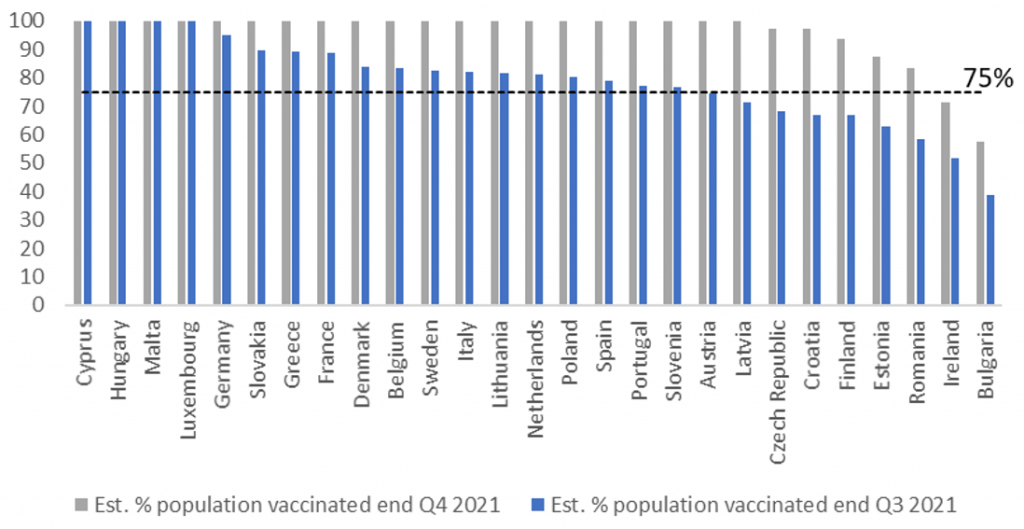

Based on current vaccines rollout trends in the EU and the daily average vaccine rates between January and May for individual countries, we have obtained figure estimates for the expected population coverage at both the end of September and the end of December 2021; the figures we obtained are broadly consistent with Bloomberg projections.

In the majority of EU member states the vaccine roll-out will be above 75% of the total population already by the end of September 2021, i.e., when the first Recovery and Resilience Facility tranche is expected to be disbursed by the Commission, while several Cohesion Countries in Central and Eastern Europe, i.e. Bulgaria, Croatia, Czech Republic, Estonia, Latvia and Romania are currently at risk of lagging behind.

Looking ahead towards the end of 2021, at current vaccination rates, only Bulgaria and Ireland will remain below the 75% threshold, with most EU member states reaching 100% vaccination rates (Figure 1). This allows us to assess which EU member states will be able to fully benefit from the first disbursement of EU funding as the vaccine rollout advances.

Figure 1: Projection as of 17 May 2021 of percentage of vaccinated population by EU member state by end of September and end of December 2021

Source: Authors’ elaboration based on Bloomberg Covid-19 Vaccine Tracker. Accessed on 17 May 2021

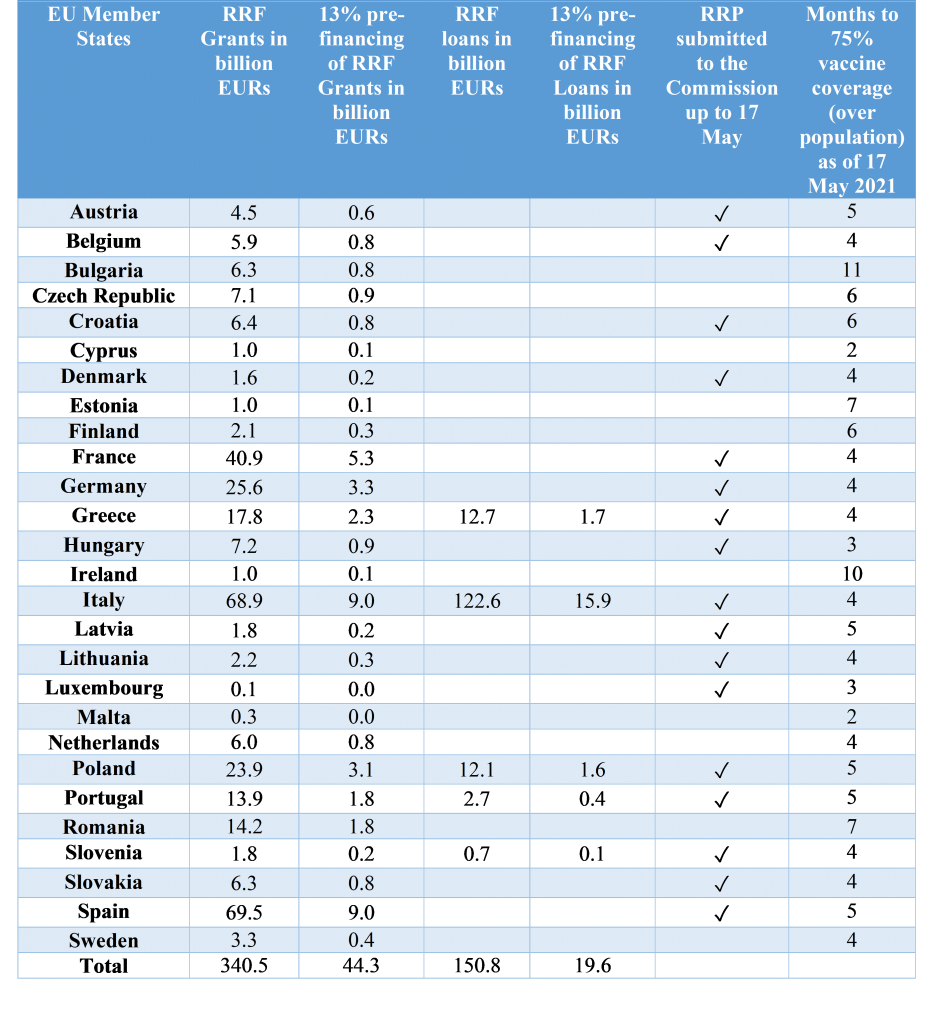

Table 1 below reports the Recovery and Resilience Facility funds disbursements’ estimates, partitioned by grants and loans, together with the estimated months needed to achieve the 75% of total population covered by Covid-19 vaccines, which – according to top infectious-disease officials – is the threshold to enable a return to normalcy.

Table 1: Recovery and Resilience Facility allocation, Recovery and Resilience Plan submission, and vaccine coverage

Sources: Authors’ elaboration based on Bloomberg Covid-19 Vaccine Tracker and European Commission

The expectation is that the Commission’s decision on which EU member states will receive the Recovery and Resilience Facility funds first will be based on merit, which include both the timing of the submission and therefore approval of the Recovery Plans as well as their compliance with the 11 criteria set out in the Recovery and Resilience Facility Regulation, including first and foremost the green and digital targets.

As shown in Table 1, Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Greece, Hungary, Italy, Lithuania, Luxembourg, Poland, Portugal, Slovenia and Spain are moving ahead both in terms of their vaccine rollouts – as of 17 May 2021 they are no more than five months away from the target of 75% vaccine coverage of their entire population – as well as in setting out their key priorities with the early submission of their respective Recovery and Resilience Plans. This in turn is likely to set in motion the disbursement of the 13% pre-financing as early as the end of the third quarter of 2021. Of these, only Italy, Greece, Poland, Portugal and Slovenia are expected to take advantage of the full firepower of the Recovery and Resilience Facility recovery package, by requesting loans to top up the existing grant allocation. This might change as member states, such as Spain, might still consider applying for Recovery and Resilience Facility loans until the ultimate deadline of August 2023.

On the other hand, of the 10 Member States that have not yet submitted their Recovery and Resilience Plans, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Finland, Estonia, Ireland and Romania are also lagging behind in terms of their vaccine rollouts. Not only will this impact the ability for their economies to quickly rebound, but the situation could also jeopardise the timeframe for disbursement of the 13% pre-financing well beyond the third quarter of 2021.

Conclusion

To conclude, the evidence suggests that the summer 2021 timing of the EU recovery fund’s initial disbursements – provided that the submitted national plans are approved within the expected timeline and that the ORD is ratified in all EU member states – is likely to coincide in a serendipitous, and not entirely planned, manner with the reopening of most EU economies thanks to the recent European vaccine roll-out take-off, boding well for an efficient and timely use of European fiscal resources.

If Italy, Spain, Greece, and Portugal had created the biggest concerns to the markets and European policy-makers at the time of the European sovereign debt crisis, the same countries of Southern Europe could this time lead by example in the EU. This is true not only in terms of their recent ramp-up of the vaccine roll-out but especially in taking seriously the Commission’s requests to allocate EU funding towards the green and digital priorities of the future, while providing full details of the requested reform programmes.

While much of the focus throughout the Covid-19 pandemic and the EU vaccine rollout has been on Western Europe, little attention has been paid to Central and Eastern Europe, where the picture is more nuanced, with some countries in the region still lagging behind when it comes to either the national delivery of the EU vaccine rollout and/or the EU recovery fund’s preparedness.

After the Covid-19 pandemic, Europe must look East, and not just South. This will be an important test for the EU’s institutions, not only for the significant and necessary transformations in terms of structural reforms, climate and digital transitions, but first and foremost for the political implications for the stability of the European project as a whole.

Note: This article represents the views of the authors and not those of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy, the London School of Economics, the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development or the National Institute of Economic and Social Research. Featured image credit: European Council