The increasing salience of issues such as immigration and the environment has altered the nature of party competition in Europe. But do these changes mean that left-right ideologies are no longer a powerful indicator of the choices voters make at the ballot box? Drawing on data from Israel, Odelia Oshri, Omer Yair and Leonie Huddy show that in the absence of partisan attachment, a left-right identity continues to provide an anchor for voters’ political decision-making.

Democratic political systems have shown growing volatility in recent years. Loyalty to traditional parties is eroding in many democracies, as partisanship declines, and support for alternative parties increases. New issues, such as immigration and the environment, have altered the nature of party competition, weakening alignment along formerly powerful left-right economic and socio-cultural axes.

It might be tempting to conclude that left-right ideology is no longer a powerful guide to voters’ political behaviour. Perhaps voters rely more on non-ideological indicators such as the charismatic nature of party leaders or the anti-establishment stance of a newly emergent party than ideology or partisanship.

However, in a recent study, we show that in the absence of strong partisanship, a strong left-right identity plays a powerful role in driving political decision-making. Even in volatile electoral systems, a left-right identity systematically affects vote choice, structures democratic politics, and clarifies social and political divisions.

We treat left-right self-placement as a social identity, suggesting that many citizens hold strong emotional and psychological attachments to an ideological group on the ‘left’ or ‘right’. Moreover, the strength of an attachment to an ideological group strongly predicts political outcomes.

Our research is part of a burgeoning literature demonstrating that emotional and psychological attachments to an ideological group, an “ideological identity,” helps to shape political behaviour and vote choice. Thus far, the influence of left-right identity has been demonstrated mostly in the American two-party system. No study of European multi-party systems has specifically examined the existence and ramifications of ideological identities.

Our research demonstrates that, in Israel – a highly fragmented and volatile multi-party system – attachment to an ideological group is strongly tied to vote choice and political engagement, and its effects are independent of, and at times more powerful than, ideology understood as issue-positions and policy preferences.

Voting for victory, not (only) for policy

In our research, we expected voters with a strong left-right attachment to display another form of loyal group behaviour: defensive or positive emotions in reaction to a threat or reassurance, respectively, to their group’s status and electoral success. Emotions in general, and anger and enthusiasm specifically, are known to propel political action and are therefore strong predictors of political participation.

We thus anticipated that voters with strong emotional and psychological attachment to an ideological group will display defensive emotions when they encounter information that threatens the status of their left or right group. Such information is seen as undermining the status of members who identify with an ideological group and therefore serves as a call to rally in its defence.

To test our hypothesis, we implemented two vignette experiments (in Study 1 we surveyed 617 Jewish Israelis, while in Study 2 we surveyed 703 Jewish Israelis; the samples were not representative of the Jewish Israeli population, but were diverse on many socio-demographic and political variables). In each experiment, respondents read a mock news article that either presented a threat or reassurance to the status of their respective ideological group (by suggesting that their ideological bloc would win or lose an upcoming election).

The purpose of this manipulation was to examine whether a left-right identity conditions an emotional reaction to group-relevant information, irrespective of one’s policy preferences. Winning or losing in the elections of course also presents a potential threat or reassurance for one’s policy preferences, which could be implemented (or not implemented) following an electoral victory (defeat) of one’s ideological bloc; and in our case, our manipulations also allowed us to test whether Israelis’ issue positions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict condition their emotional reactions to the vignettes, irrespective of their left-right identity.

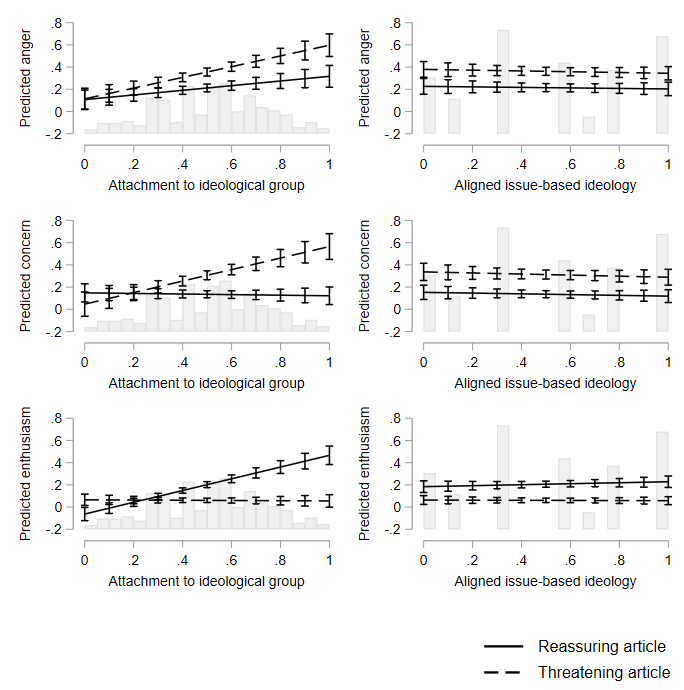

As expected, in both experiments we found that those who most identified with their ideological group felt most negative when their group’s status was threated and felt most positive when reassured (see left-hand panels in Figure 1 below, which shows results from our Study 1 experiment). But issue positions on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict do not condition one’s emotional reactions to the vignettes (see right-hand panels in Figure 1 below). Our findings shed light on the underpinnings of voters’ ideological loyalty and attendant actions to protect and strengthen the status of their respective ideological camps, even at the expense of supporting their camp’s policy positions.

Figure 1: Ideological attachment, issue positions and emotional reactions

Note: The figure shows the relationship between an individual’s attachment to their ideological group and their emotional response to reassuring/threatening articles (left panel) and the relationship between their position on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict and emotional responses to the same articles. For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper.

To return to our original question, voters’ ideological identities can mitigate the impact of partisan instability and foster closer alignment between citizens and policymakers. Even as the electoral fortunes of individual parties rise and fall, the share of votes allocated to an ideological bloc can remain stable.

Group attachments also enhance political representation. Although the importance of party identification to vote choice has declined in some settings in recent years, the link between citizens and elected politicians in parliamentary systems is nonetheless largely sustained by citizens’ attachment to an ideological bloc. Parties can therefore gain popular support by belonging to a major left-right bloc. This will work best in multi-party political systems dominated by a strong left-right axis.

A disregard of voters’ attachment to ideological groups might therefore hinder parties’ efforts to communicate with voters and obtain their support. From this perspective, voters’ attachment to an ideological group not only stabilises the party system, but also enhances representative democracy.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper at Party Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Mika Baumeister on Unsplash