Did the educational background of world leaders make a difference to responses to the Covid-19 pandemic? Drawing on a new study, Timon Forster and Mirko Heinzel present evidence that leaders with higher levels of educational attainment were more likely to listen to the advice of experts when the first outbreaks emerged.

When the Covid-19 pandemic hit countries in early 2020, citizens turned to their leaders for solutions. They expected heads of government to make sense of the new situation, present a coherent narrative, and facilitate effective policy responses. Soon it became apparent that some leaders rose to the challenge, while others did not.

The press identified individual leaders as being responsible for ‘good’ or ‘bad’ crisis management. Government responses by leaders such as New Zealand’s Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern or Germany’s Chancellor Angela Merkel were hailed as success stories, while the policies adopted under Brazil’s Jair Bolsonaro or Belgium’s Sophie Wilmès were criticised. Similarly, academic research took up the question of crisis leadership. Studies demonstrate how government responses differ by gender, scientific training, or populist attitudes.

In a new study, we probe whether governments whose leaders rely more heavily on experts responded differently to a Covid-19 outbreak in their countries. We depart from the observation that the pandemic revived both demand for technocratic decision-making and levels of scepticism towards expert advice. The United States serves as perhaps the starkest example.

Former President Donald Trump – who famously promoted himself as a “very stable genius” – made his scepticism towards scientific expertise a point of personal and professional pride as soon as he entered the political arena. Trump was engaged in a public fight with his leading scientists for much of the pandemic. Dr Anthony Fauci, the director of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, warned one week after the first reported case in the United States that “things are going to get worse before they get better” and soon cautioned that Covid-19 “could turn into a global pandemic”.

At the same time, Trump claimed: “It’s one person coming in from China, and we have it under control. It’s going to be just fine”. He also echoed those statements over the coming weeks and months. He repeatedly claimed – against the advice of his experts – that the pandemic would simply disappear with the heat, he posited hydroxychloroquine as a cure, and he even suggested that injecting disinfectant should be tested. A recent Lancet commission estimated that the Trump administration was responsible for 40% excess Covid-related deaths compared to similar countries that responded differently. The US does not seem to be an isolated case, though. Similar patterns of politicians questioning the advice of experts have been observed all over the world, from Sweden to Brazil.

We look at differences in the educational background of world leaders that plausibly signify a propensity to incorporate scientific advice in the sense- and decision-making of the pandemic. Specifically, we collected data on the educational background of world leaders to identify those government heads who received extensive academic training as part of a doctoral degree.

We expect that such leaders would be more likely to understand and value the process through which public health advice gets generated and, hence, be more inclined to listen to experts. Yet, we do not assume that they rely blindly on such advice. Instead, early Covid-19 outbreaks were a unique situation in which listening to experts made a difference but was also politically feasible.

Research on societal crises identifies uncertainty as a key feature. Of course, the consequences of policies are always unpredictable. But in times of crisis, neither problems nor solutions are clearly understood. This was particularly the case in the early weeks of the Covid-19 pandemic. It was unclear whether the outbreak would turn into a global pandemic or fade away quickly – like many of the diseases that had made headlines in the past. However, by March 2020, the severity of the disease was widely acknowledged and a general playbook for Covid-19 responses had emerged.

It was in these crucial early months, we argue, where the technocratic mentality of world leaders was consequential. Leaders who relied more on scientific advice were quicker to accept the uncomfortable truth that Covid-19 had the potential to turn into the biggest public health threat the world had faced in over a century, endangered the health of millions globally, and could transform the public life that globalised societies had become accustomed to. Hence, their countries would have responded quicker with restrictive pandemic containment measures once the virus had reached their shores.

In our statistical analysis, we find support for this argument. We combined novel data on the educational background of leaders with data on Covid-19 pandemic responses globally collected by the team of the Oxford Coronavirus Government Response Tracker. Countries headed by leaders with academic training (approximated by holding a doctorate) responded quicker in the early weeks of the pandemic.

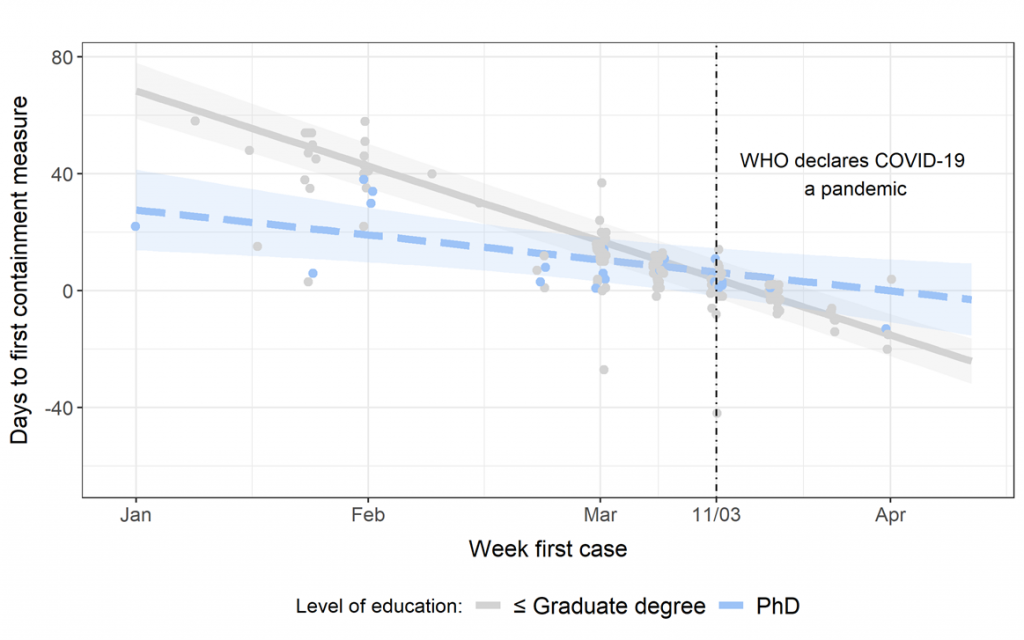

We illustrate this in Figure 1, which shows that the predicted number of days between the first reported Covid-19 case and the first restrictive containment measure for world leaders with doctorates, the blue dashed line, lies below the grey fit for world leaders without academic training for countries that reported the first case of Covid-19 early in the pandemic. Put differently, governments headed by world leaders who received academic training reacted faster than others. But only up until March, around the time the WHO declared Covid-19 a global pandemic, when these differences disappear.

Figure 1: Time to first containment measure

Note: The fitted lines are from our baseline statistical models. The points (jittered to reduce overlap) are observed data for 161 countries in our sample.

What does this all mean for leadership during Covid-19 and other crises? Countries whose leaders received academic training responded faster to an early outbreak, potentially saving thousands of lives. Our argument suggests that this is due to the different reliance on scientific evidence, which facilitated earlier sense- and decision-making. Our study may offer a pivotal piece to the puzzle of understanding how governments negotiate the potentially conflicting goals of protecting public health, safeguarding their economy, and respecting legal constraints.

However, when experts offer competing interpretations, leaders might favour one expert community over another. Hence, in societies with technocratically inclined leaders, crisis decision-making may not necessarily follow deliberative ideals. The Covid-19 pandemic suggests the actions incurring these deliberative costs may have saved thousands of lives by facilitating a coherent and swift response. However, reliance on science cannot replace political debate on the relative importance of competing objectives, like personal freedom versus public health. Hence, technocratic decision-making intensifies the need for leadership to be scrutinised in times of crisis.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in the Journal of European Public Policy

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Council