The rise of right-wing populism has been a feature of European politics over the last fifteen years. Drawing on a new report, Daphne Halikiopoulou and Tim Vlandas explain what we have learned about the appeal of right-wing populist parties, and what other parties can do to counter their success.

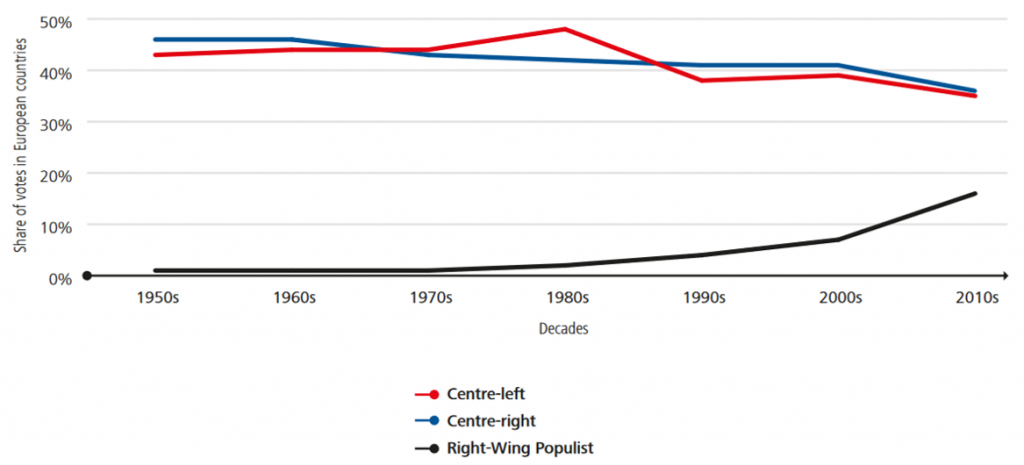

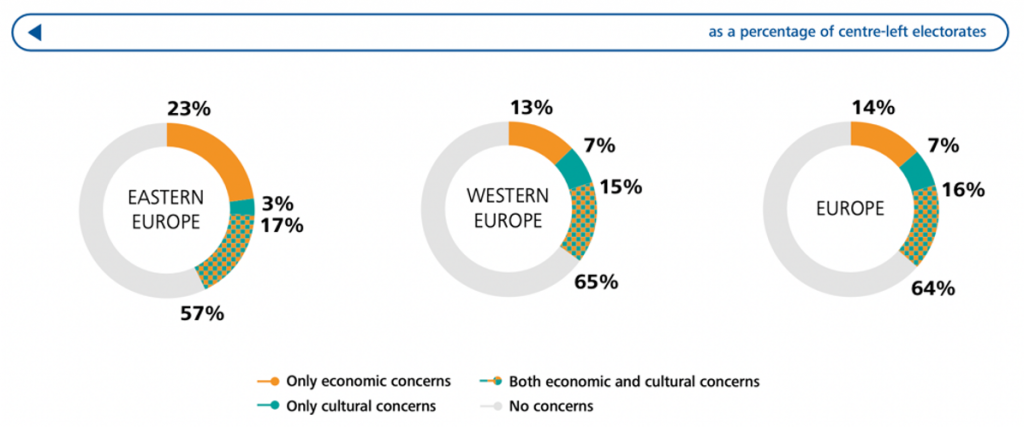

Following a varied and more subdued performance in the 1990s and early 2000s, the 2008 financial crisis and the 2015 refugee crisis spurred an increase in right-wing populist party support across Europe. Worryingly, these developments have taken place at the expense of the mainstream: while the average electoral score of right-wing populist parties has been steadily increasing over time, support for both the mainstream left and right has declined (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The rise of right-wing populist parties has come at the expense of both the mainstream left and right

Source: Compiled by the authors.

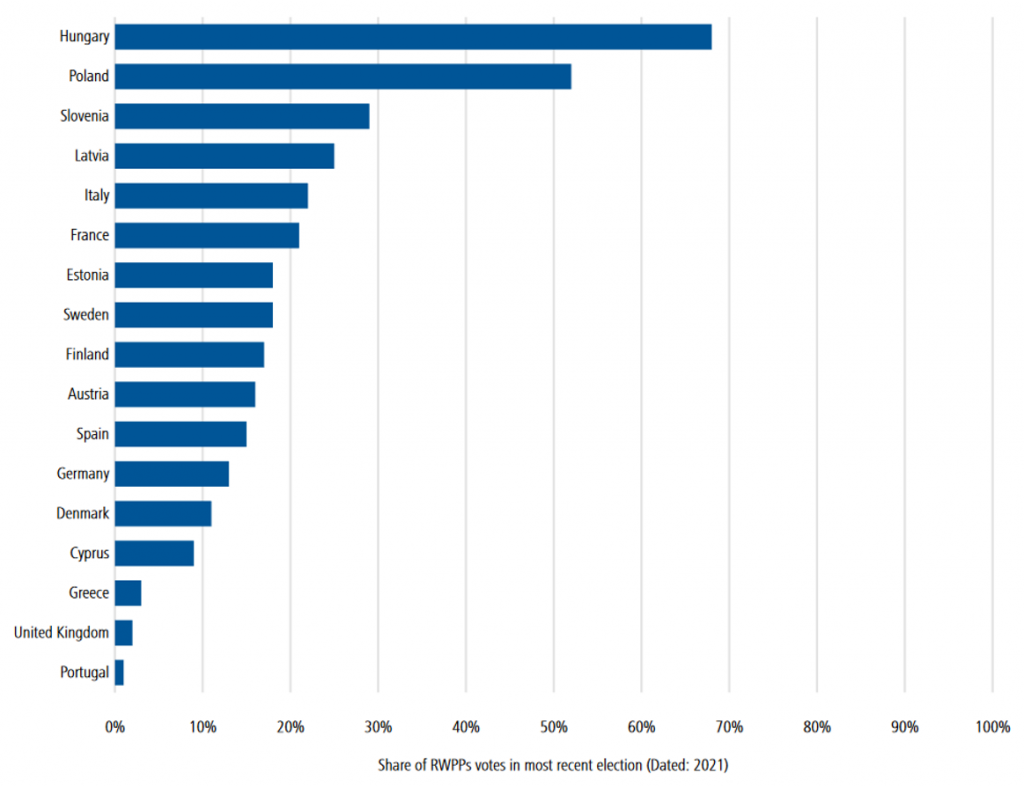

This right-wing populist momentum sweeping Europe has three key features. First, there has been the successful electoral performance of parties pledging to restore national sovereignty and implement policies that consistently prioritise natives over immigrants. Many right-wing populist parties have improved their electoral performance over time, although there remain important cross-national variations (Figure 2).

The French Rassemblement National (RN), the Austrian Party for Freedom (FPÖ), and the German Alternative for Germany (AfD) have all increasingly managed to mobilise voters beyond their support core groups, significantly increasing their support in their domestic electoral arenas. At the same time, countries previously identified as ‘outliers’ because of the absence of an electorally successful right-wing populist party are no longer exceptional – such as Portugal with the rise of Chega and Spain with the rise of Vox.

Figure 2: Cumulative share of right-wing populist party votes received in most recent election

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Second, there has been an increasing entrenchment of these parties in their respective political systems through access to office. A substantial number of right-wing populist parties have either governed recently or served as formal cooperation partners in right-wing minority governments. Examples include the Lega in Italy, the FPÖ in Austria, Law and Justice (PiS) in Poland, Fidesz in Hungary, the Danish People’s Party (DF), and the National Alliance (NA) in Latvia. The so-called cordon sanitaire – the policy of marginalising extreme parties – has broken down even in countries where it has been traditionally effective, such as Estonia and Sweden.

Third, right-wing populist parties have increasingly gained the ability to influence the policy agenda of other parties. Parties such as the Rassemblement National, the Sweden Democrats and UKIP have successfully competed in their domestic systems, permeating mainstream ground and influencing the agendas of other parties. As a result, mainstream parties on the right and, in some instances, on the left have often adopted accommodative strategies – mainly regarding immigration.

Understanding the rise of right-wing populist parties

What explains this phenomenon? Researchers and pundits alike tend to emphasise the political climate of right-wing populist normalisation and systemic entrenchment, where issues ‘owned’ by these parties are salient: immigration, nationalism and cultural grievances. The importance of cultural values in shaping voting behaviour has led to an emerging consensus that the increasing success of right-wing populist parties may be best understood as a ‘cultural backlash’.

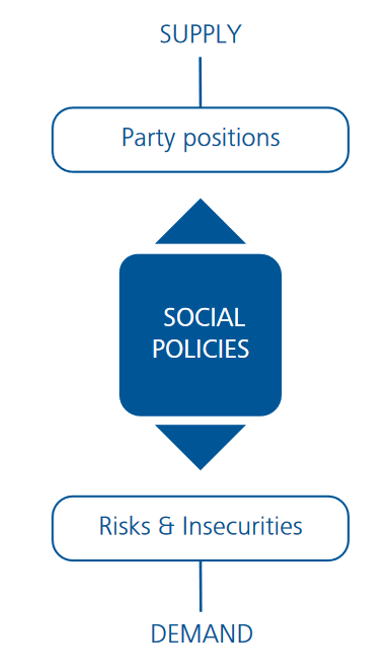

Figure 3: The demand, supply and policy levels

Source: Compiled by the authors.

A sole focus on culture, however, overlooks three key issues at the demand, supply and policy levels, as illustrated in Figure 3 above. First, the predictive power of economic concerns over immigration and the critical distinction between galvanising a core constituency on the one hand and mobilising more broadly beyond this core constituency on the other. Second, the strategies right-wing populist parties themselves are pursuing to capitalise on multiple insecurities, including both cultural and economic. And third, the role of social policies in mitigating those insecurities that drive right-wing populist party support.

People

To address these issues, in a new report we examine the interplay between what we call the ‘three Ps’: people, parties and policies. With respect to people, a key question is how cultural and economic grievances affect individuals’ probability of voting for a right-wing populist party. Similarly, how are these grievances distributed among the right-wing populist party electorate?

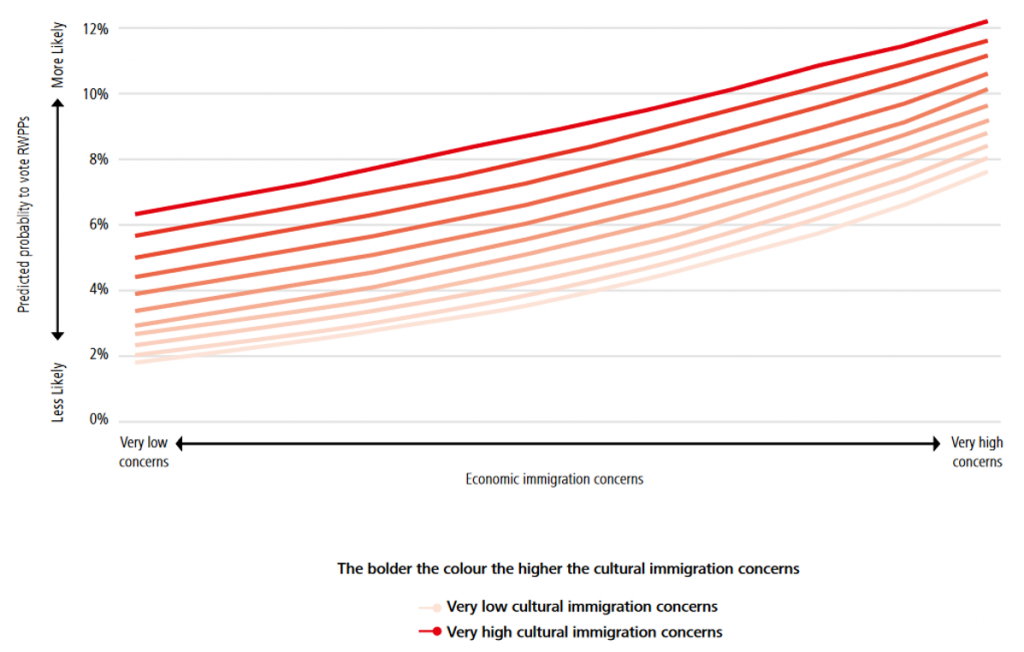

We argue that the assumption that immigration is by default a cultural issue is at best problematic. Both cultural and economic concerns over immigration increase the likelihood of voting for right-wing populist party (Figure 4).

Figure 4: Predicted right-wing populist party vote for different levels of cultural and economic concerns over immigration

Source: Compiled by the authors.

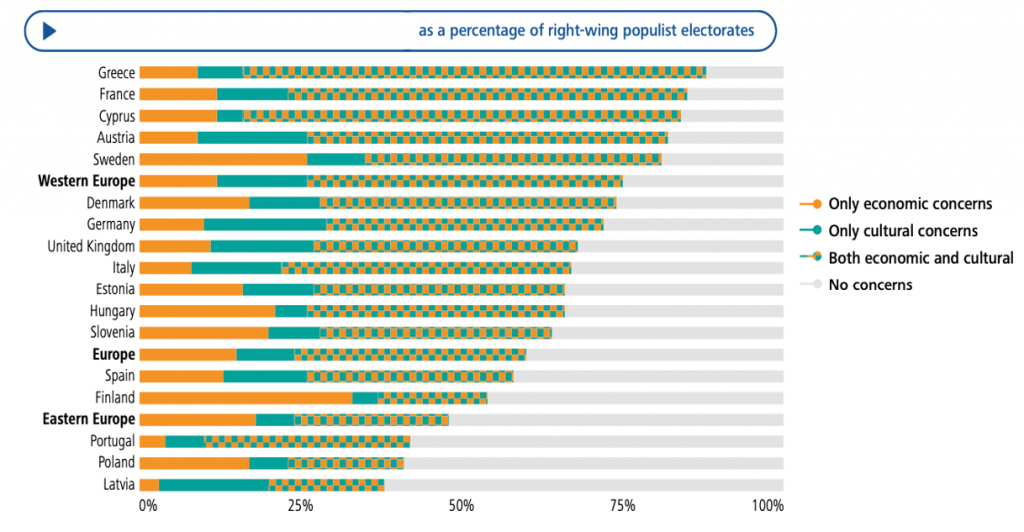

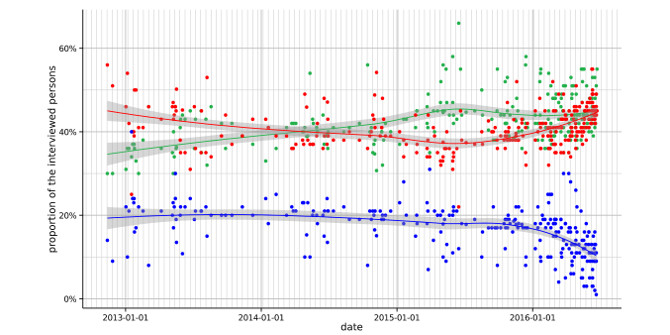

However, while cultural concerns are often a stronger predictor of right-wing populist voting behaviour, this does not automatically mean that they matter more for the success of right-wing populist parties in substantive terms because people with economic concerns are often a numerically larger group. The main issue to pay attention to here is size: as shown in Figure 5, many right-wing populist party voters do not have exclusively cultural concerns over immigration.

Figure 5: Distribution of immigration concerns

Source: Compiled by the authors.

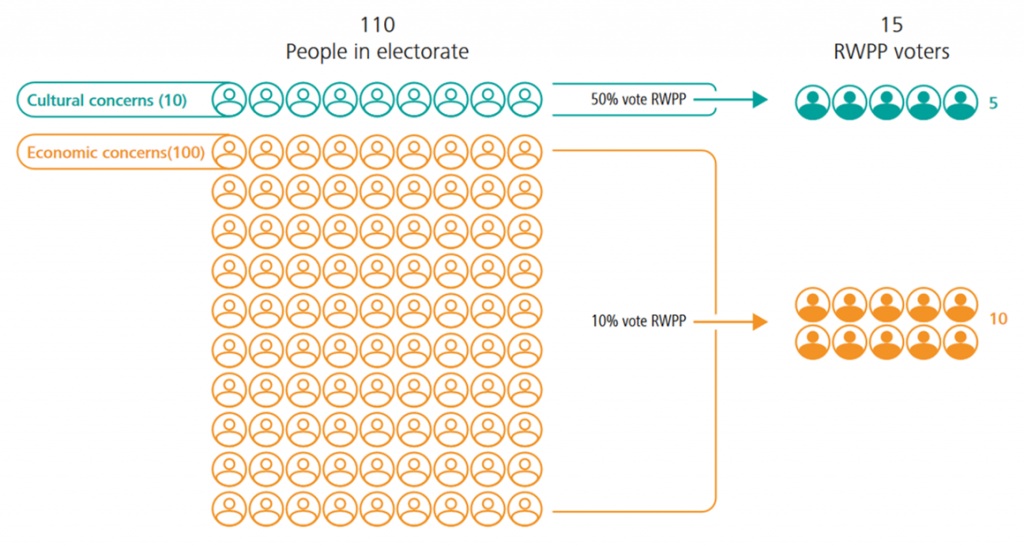

This suggests we must distinguish between core and peripheral voter groups. Voters primarily concerned with the cultural impact of immigration are core right-wing populist party voters. Although they might be highly likely to vote for right-wing populist parties, they also tend to be a numerically small group. By contrast, voters that are primarily concerned with the economic impact of immigration are peripheral voters. They are also highly likely to vote for right-wing populist parties, but in addition they are a numerically larger group. Since the interests and preferences of these two groups can differ, successful right-wing populist parties tend to be those that are able to attract both groups.

Figure 6: Hypothetical representation of difference between predictive power and substantive importance

Source: Compiled by the authors.

What determines right-wing populist party success is therefore the ability to mobilise a coalition of interests between core and peripheral voters. As the hypothetical example in Figure 6 shows, it is possible that right-wing populist parties galvanise voters with cultural concerns over immigration, while at the same time their success is dependent on their ability to mobilise economically concerned voters more broadly.

Parties

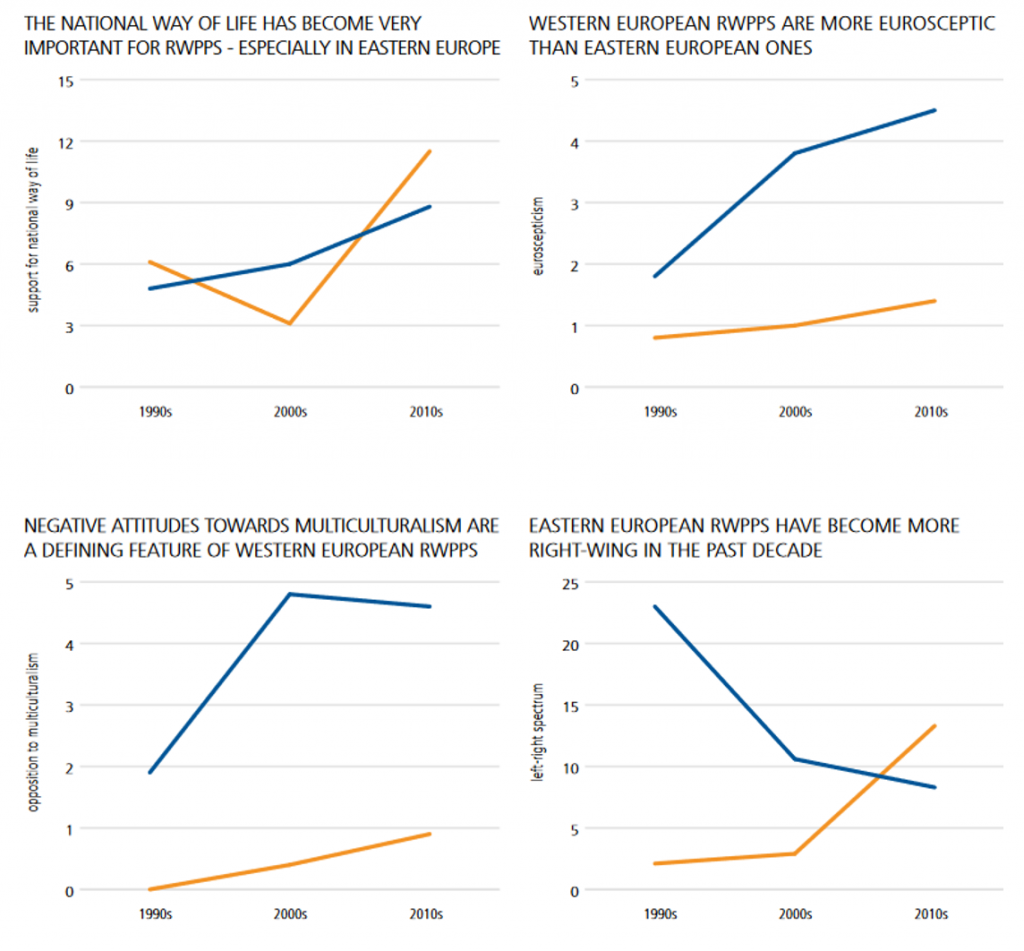

What strategies do right-wing populist parties adopt to capitalise on their core and peripheral electorates? While we examine the success of parties that tend to be defined as ‘right-wing populist’, we are also sceptical about the analytical utility of the term ‘populism’ to explain the rise of this phenomenon. Instead, we emphasise the importance of nationalism as a mobilisation tool that has facilitated right-wing populist party success. Right-wing populist parties have increasingly emphasised the “national way of life” (Figure 7).

Right-wing populist parties in Western Europe employ a civic nationalist normalisation strategy that allows them to offer nationalist solutions to all types of insecurities that drive voting behaviour. This strategy has two features: it presents culture as a value issue and justifies exclusion on ideological grounds; and focuses on social welfare and welfare chauvinism.

Figure 7: Value policy priorities of RWPPs in Western and Eastern Europe

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Eastern European right-wing populist parties, on the other hand, remain largely ethnic nationalist, focusing on ascriptive criteria of national belonging and mobilising voters on socially conservative positions and a rejection of minority rights. Eastern European right-wing populist parties are also more likely to emphasise negative attitudes towards multiculturalism (Figure 7).

Policies

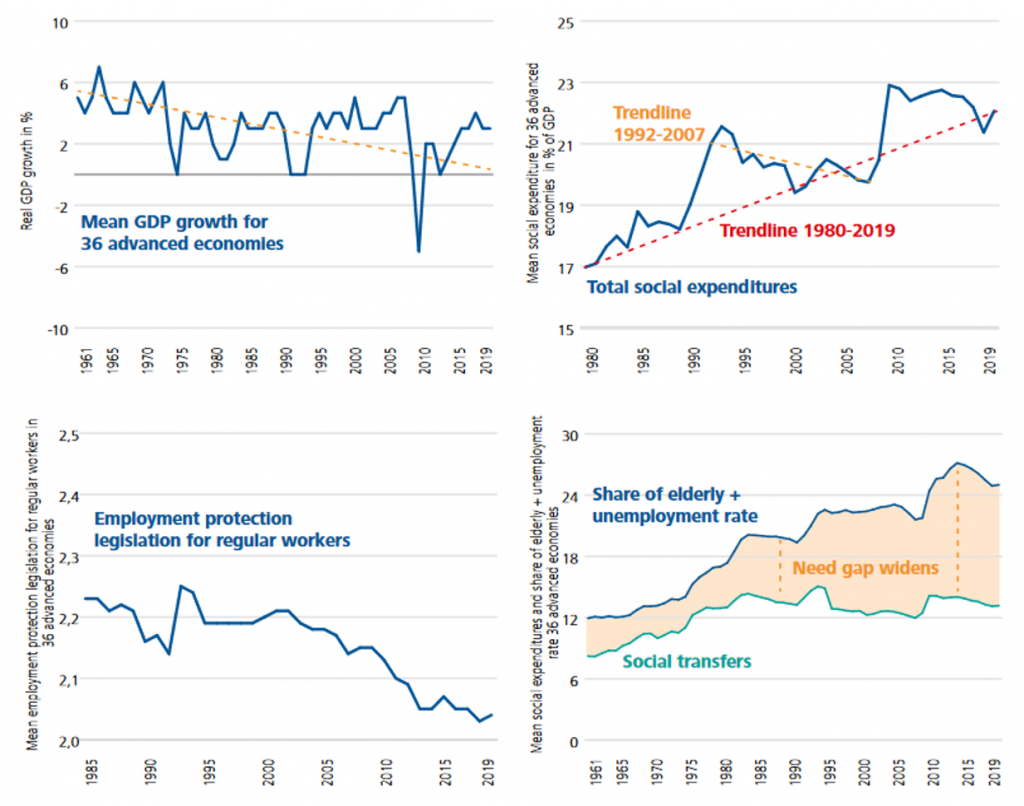

What type of policies can mitigate the economic risks driving different social groups to support right-wing populist parties? European democracies have operated in a context of falling economic growth rates over recent decades, with recurrent economic crises in the 1970s, early 1990s and from 2008 onwards.

Many advanced economies have in time recovered, but growth has often not returned to the level of previous decades and achieving low inflation has been a policy priority. Many governments have liberalised and ‘activated’ their labour markets (Figure 8) often at the expense of a growing group of so-called labour market outsiders in precarious contracts.

Figure 8: Rising expenditures and liberalised labour markets in the context of falling growth and increased needs

Source: Compiled by the authors.

In addition, accumulating debt is leading to a climate of permanent austerity while constraining the necessary physical and social investments that could underpin future growth. While economic developments obviously affect the life chances and insecurities of individuals, as well as the risks that they face, the degree of redistribution and the social insurance provided by developed welfare states shapes their prevalence and political consequences.

Welfare state policies moderate a range of economic risks individuals face. Our analysis illustrates that this reduces the likelihood of supporting right-wing populist parties among insecure individuals – for example, the unemployed, pensioners, low-income workers and employees on temporary contracts.

Our key point here is that political actors have agency and can shape political outcomes: to understand why some individuals vote for right-wing populist parties, we should not only focus on their risk-driven grievances, but also on policies that may moderate these risks. This is consistent with a larger political economy literature documenting the protective effects of welfare state policies on insecurity and inequality.

What to do about it?

While this is a broad phenomenon, there is no single success formula for right-wing populist parties. Our analysis identifies regional patterns and different voter bases and grievances driving right-wing populist party success across Europe. Progressive strategies addressing those necessarily face different obstacles depending on the context. For instance, the Western European centre-left has a better chance of focusing on welfare expansion as an issue they ‘own’ than many counterparts in Eastern Europe who have lost the ownership of those issues to right-wing populist parties that promote distorted nationalist and chauvinist versions of similar ideas.

Centre-left parties should not be fooled into thinking they can simply copy the right-wing populist party playbook by going fully populist and embracing restrictive immigration policies and questions of national identity. Instead, they should appeal to the economic insecurities that many peripheral right-wing populist party voters are concerned about, focusing on an issue the centre-left ‘owns’ such as equality. After all, centre-left voters tend to be pro-immigration and a nationalist turn will likely alienate them.

Figure 9: Distribution of immigration concerns as a percentage of centre-left electorates

Source: Compiled by the authors.

Successful centre-left strategies must attempt to galvanise the centre-left’s core voter base, addressing the (economic) grievances that concern much larger parts of the whole electorate. Therefore more energy should be invested into thinking about new social investment strategies, growth regimes and/or a universal basic income, rather than focusing purely on the cultural concerns of a small part of the electorate.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying report

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Presidenza della Repubblica (Public Domain)

I’ve noticed that references to “universal basic income” (UBI) appear rather frequently on this EUROPP blog, almost as though it has become common wisdom amongst all economic and social science experts. I assume UBI means “the same money given to all the adult population with no means testing”. It is in fact far from common sense, and I see no feasible way to implement a truly universal benefits system, unless the “Modern Monetary Theorists” were correct that unlimited deficit spending is possible without incurring extreme inflation.

A simple debunking of UBI can be read here: https://www.johnkay.com/2016/06/01/simple-arithmetic-shows-why-basic-income-schemes-cannot-work/

(I certainly agree with the MMT crowd that “full employment” aka “a job for anyone who wants one” is possible – but there remains a large percentage of the population unable to work, so this is hardly UBI)

As has been said by those interested, mainstream welfare systems have their faults, but are far preferable to the “universal” alternative. A good benefits system has at least the following features:

(1) Targeted towards those most in need

(2) Moderate burden on public expenditure (no more than 30% GDP)

(3) Incentivises work – it should be fair by ensuring that those who earn an income do not lose more benefits than they gain from employment, hence tapering

(4) Does not unduly stigmatise those who receive it

(5) Balances providing for those in desperate need with investment in preventative measures, such as improved education, healthcare and work opportunities.

(6) Not determined in isolation, but along with other policies for poverty relief and improved equality, such as minimum wage, taxation and economic growth.

It is therefore unavoidably complicated.

UBI advocates rightly point out that means-tested benefits can result in stigmatisation. However, it seems extreme to address this by insisting on equal benefits for millionaires as for the poor! There are well known ways to address such stigmatisation without resort to UBI – for example, school meals could be provided for all children regardless of income. Investing in subsidised public transport would make it more feasible for low income earners to travel further for work without losing more than they gain, and without having to give out “stigmatising” free passes (although I doubt travel passes for low income earners would be particularly stigmatising if only the means testing could be less intrusive!)

Perhaps the real problem here is that the voice of low income earners gets diluted in modern democracies, crowded out by the well funded lobbyists and middle class votes. This means politicians have an incentive to cut welfare spending and make it harder and harder to obtain enough mean-tested benefits to live on. Having some kind of legislative chamber with stronger representation for the poor might be the solution to this.