Research suggests a majority of people in Russia support their country’s military actions in Ukraine. But what do those who support the war think about those who oppose it? Using an online experiment, Philipp Chapkovski and Alexei Zakharov illustrate the extent to which ordinary Russians are willing to punish fellow citizens for their anti-war views.

The war that Russia is waging in Ukraine has not only brought about enormous human suffering but has also deepened political divisions in Russian society. A majority of Russians support the war to varying degrees, and a substantial minority oppose it. However, the true size of each group is hard to establish, not least because the state has threatened opponents of the war with enormous fines and prison sentences of up to 15 years.

Given this context, it is unsurprising that many of those who oppose the war are reluctant to say so. Some previous EUROPP articles have already discussed this issue of preference falsification and even provided rough estimates of it. What is apparent, however, is that there is growing evidence of increasing animosity between those who support the war and those who oppose it, sometimes even running within single families.

With the government on their side, war supporters have an asymmetric power balance over those who oppose the war. Government supporters are known to be actively involved in identifying dissidents: from pupils reporting on their teachers, to people informing the police about ‘suspicious neighbours’, and mothers denouncing their daughters to the police. At the same time, there have been some incidences of animosity in the opposite direction, such as vandalism directed against cars displaying pro-war symbols.

All of these incidents are hallmarks of so called ‘affective polarisation’ – the phenomenon of ordinary people distrusting, ostracising, and discriminating against those who hold opposing views on political issues. Affective polarisation is an increasingly important characteristic of politics in several democratic countries, particularly the United States.

In an authoritarian context, affective polarisation may contribute to an authoritarian regime’s sustainability because it leaves little space for dissidents to hide. It allows the vertical power of authoritarian regimes to be reinforced by the stability of horizontal control. Previous research has documented this effect in European fascist regimes and China, among other states. But to what extent are ordinary Russians ready to punish fellow citizens for their opposition to the war in Ukraine?

An online experiment

To answer this question, we conducted an online experiment on the crowdsourcing platform Toloka. We recruited 2,000 Russians to play a variation on a simple give-or-take dictator game that is widely used as a tool for measuring affective polarisation. In this game, people were separated into pairs with each person in a pair being either assigned the role of a ‘dictator’ or a ‘recipient’. Dictators were initially assigned a bonus for participating of $1.00, while recipients were assigned $0.50. Dictators were then asked to decide whether to reward the recipient by transferring some of their bonus or fine them by taking up to 50 cents of their allocation and adding it to their own.

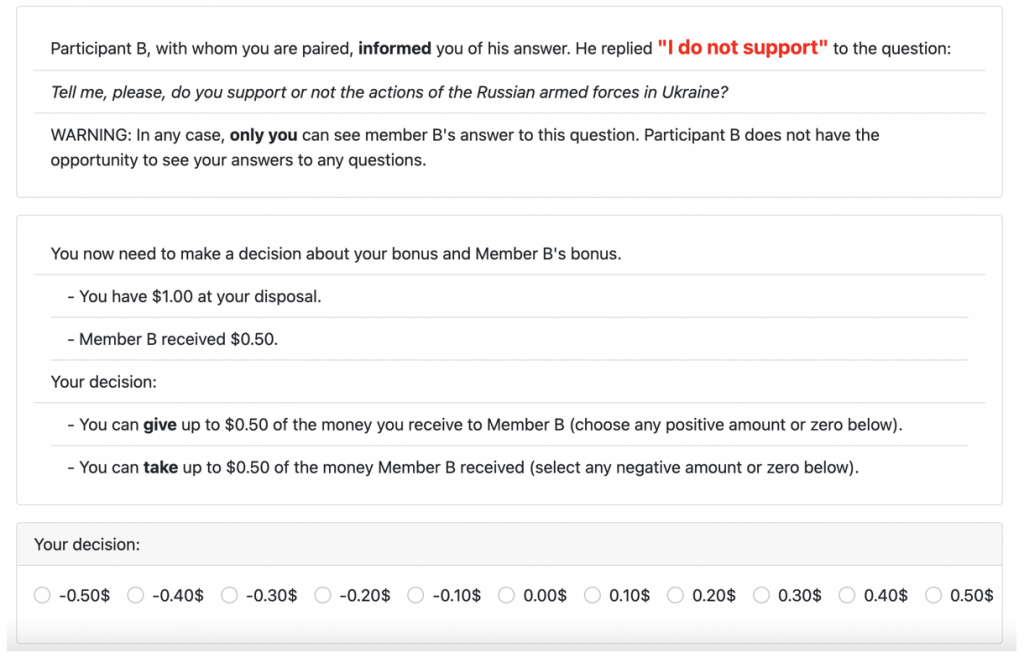

When we ran this experiment, we selected 1,000 dictators from among people who supported the war and matched them with 500 pro-war and 500 anti-war recipients. Dictators then established their partners’ positions regarding the war and decided to reward or fine them. Figure 1 below shows a translated example of the instruction screen shown to dictators when they were asked to make their decision.

Figure 1: Decision screen shown to ‘dictators’ during the experiment (anti-war recipient)

Note: This screenshot is provided for illustrative purposes. Google Translate has been used to translate the original Russian text into English. Three different screens were shown to dictators – one with text stating that the recipient had replied “I do not support” to the question about the war; one indicating the recipient had replied “support” to the question; and one indicating the recipient had “refused” to answer the question.

We realise that this way of measuring polarisation can be misleading. In real life, people usually avoid exposing their views either to strangers or to friends in order to avoid conflict. Moreover, people may themselves avoid learning this information about their counterparts. To have a more nuanced picture, dictators were assigned one of three scenarios: a ‘forced reveal’ scenario, a ‘recipient reveals’ scenario, and a ‘dictator reveals’ scenario’.

In the ‘forced reveal’ scenario, dictators were either shown the position of their partner or were informed that the computer had randomly decided not to show them this information. In the ‘recipient reveals’ scenario, dictators saw their partner’s position only if the recipient chose to disclose it. Finally, in the ‘dictator reveals’ scenario, dictators were able to decide themselves whether they wanted to see their partner’s opinion or not.

Results

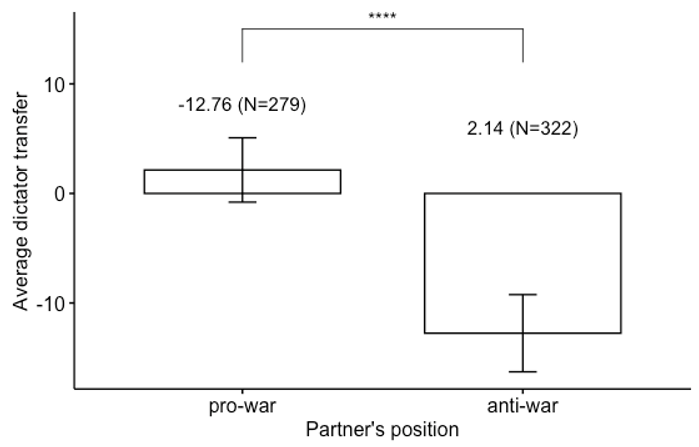

In all three scenarios, the dictators substantially punished those who supported the war. On average, there was a gap of around 15 cents between pro and anti-war recipients: dictators who observed that they were matched with partners that supported the war sent them on average around 2 cents, while they took about 13 cents from recipients who did not support the war, as shown in Figure 2 below.

Figure 2: Difference in dictators’ transfers to pro-war and anti-war recipients

Note: The number of participants was 601. The bars show average transfers, with the vertical lines indicating 95% confidence intervals. The figure shows that on average, pro-war recipients were transferred 2.14 cents, while anti-war recipients were deducted 12.76 cents. The result of a t-test of difference in means is shown at the top of the graph with the significance levels denoted as: *: p <= 0.05, **: p <= 0.01, ***: p <= 0.001, ****: p <= 0.0001.

This gap grew larger with the intensity of dictators’ support for the war. On average, those dictators who ‘fully’ rather than ‘somewhat’ supported the war had a gap of around 20 cents in their transfers (a deduction of around 15 cents for anti-war recipients and a transfer of around 5 cents for pro-war recipients). All of the differences reported here are statistically significant.

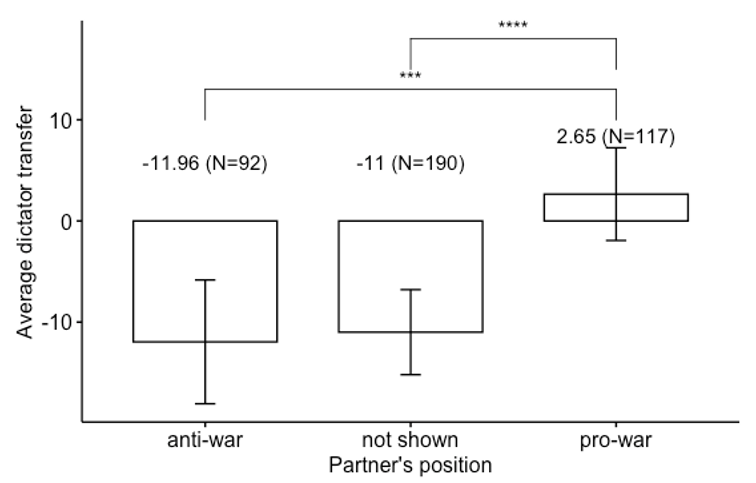

We also compared average transfers to anti-war and pro-war recipients with those to recipients whose positions were hidden from dictators. Those dictators who were informed that they could not observe their recipient’s position (either because a recipient had withdrawn this information or because the information was withdrawn by the computer) punished them almost to the same extent as they did with confirmed anti-war recipients, as shown in Figure 3 below.

Figure 3: Difference in dictators’ transfers to pro-war, anti-war, and ‘unknown’ recipients

Note: This figure is based on 399 participants in the ‘recipient reveal’ group. The bars show average transfers, with the vertical lines indicating 95% confidence intervals.

The willingness to punish recipients whose positions regarding the war were unknown can be explained by beliefs about those who hide their views. We asked the dictators whose recipients were able to hide their position a further question to measure this effect. Dictators were asked to estimate how many pro-war and anti-war recipients would be willing to disclose their opinion. On average, dictators believed that 64% of pro-war recipients would disclose their opinion, while they believed that only 43% of anti-war recipients would do so, as shown in Figure 4 below.

Figure 4: Dictator estimates of how many pro-war and anti-war recipients would disclose their views about the war

Note: This figure is based on 399 participants in the ‘recipient reveal’ group. The bars show average estimates, with the vertical lines indicating 95% confidence intervals.

The dictators were interested in knowing the recipient’s views about the war. In one of our scenarios, dictators were able to choose whether to observe the recipient’s answer. In our study, only 16% of dictators turned down the opportunity to learn about their partner’s views – this is significantly lower than the 30% that we observed in a previous study (also conducted with a Russian audience in Toloka) where people were given the option to observe a recipient’s views on same-sex marriage. Thus, we observe a substantial demand for the partner’s position regarding the war, and when this information is unavailable partners are perceived with hostility.

Our results are evidence of political polarisation in Russian society, with the Russian-Ukrainian war in particular being a divisive issue. Partisan political identity can drive costly social behaviour to be directed against people with opposing views. A silver lining to these uncomfortable results is that people do change their beliefs about the overall degree of war support based on personal encounters.

We asked dictators to guess the proportion of pro-war supporters who participated in the study (the true number was 70.9%). Those who were matched with a pro-war recipient estimated this proportion to be 8% higher than those who were matched with an anti-war recipient. This suggests that exposure to those with a different perspective on the war does have some effect on people’s perceptions – a small ray of hope for a society where people are increasingly hostile toward those with opposing views.

Note: The data for this study was collected on 2 June 2022. The data, otree script, and code used for producing the figures can be found on Harvard’s Dataverse. The article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Markus Spiske on Unsplash