Giorgia Meloni, the leader of the far-right party Fratelli d’Italia, was sworn in as the new Italian Prime Minister on 22 October. But what will Meloni’s government mean for the far right across Europe? Using data from votes in the European Parliament, Adam Holesch and Piotr Zagórski show that far-right parties are likely to remain divided over Russia, but that Meloni could prove to be an important ally for the Hungarian and Polish governments in debates over the rule of law.

Fratelli d’Italia’s victory in the recent Italian election has left many observers asking whether we are about to witness a new wave of ‘illiberal’ governments, joining those already present in Hungary and Poland. While Italy’s relatively stable democratic institutions – as well as the short-lived nature of previous Italian governments – should give some reason to temper these concerns, it remains to be seen how a far-right Italian government might influence democracy within the European Union.

Russia and the European far right

One particularly concerning possibility is that a unified European far right could disrupt the EU’s response to Russia’s war in Ukraine. The most robust institutional links between the governing parties in Hungary, Italy and Poland are those between Fratelli d’Italia and Law and Justice in Poland, which are both members of the European Conservatives and Reformists (ECR) group in the European Parliament. However, Hungary’s ruling party, Fidesz, which left the European People’s Party (EPP) group in 2021, has become a strong advocate of a united European populist right.

The big players in this informal group are two of the new Italian coalition, Fratelli d’Italia and Matteo Salvini’s Lega, alongside Fidesz, Law and Justice, Marine Le Pen’s French Rassemblement National (RN), the Spanish Vox, and the Flemish Vlaams Belang (BE). The German Alternative for Germany (AfD) and the Austrian Freedom Party (FPÖ) are still not fully included in these structures.

The ideology of these parties derives from similar illiberal or populist radical right ideas, such as nativism, authoritarianism, majoritarianism and anti-elitism. Anti-Putinism, however, divides them. During the far-right meeting in Warsaw in December 2021, Marine Le Pen argued that Ukraine belongs to Russia’s sphere of influence, shocking the Polish hosts, which are known for their hawkish position toward Russia.

The meeting in Madrid in January 2022 showed even more cracks. While the Polish delegation insisted on a Russia-critical reference in the conclusions, Orbán did not criticise Putin, and Le Pen did not sign the declaration. Matteo Salvini and Fratelli d’Italia’s leader, Giorgia Meloni, were not present at this meeting. However, their attitude towards Russia seemed to be clear. While Meloni has positioned her party as clearly anti-Putin, Salvini has often defined himself as a friend of the Russian leader, even publicly wearing a shirt with Putin’s image. While initially changing his rhetoric following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Salvini planned to visit Moscow in May 2022, damaging the anti-Russian front of the Draghi government.

Voting patterns in the European Parliament

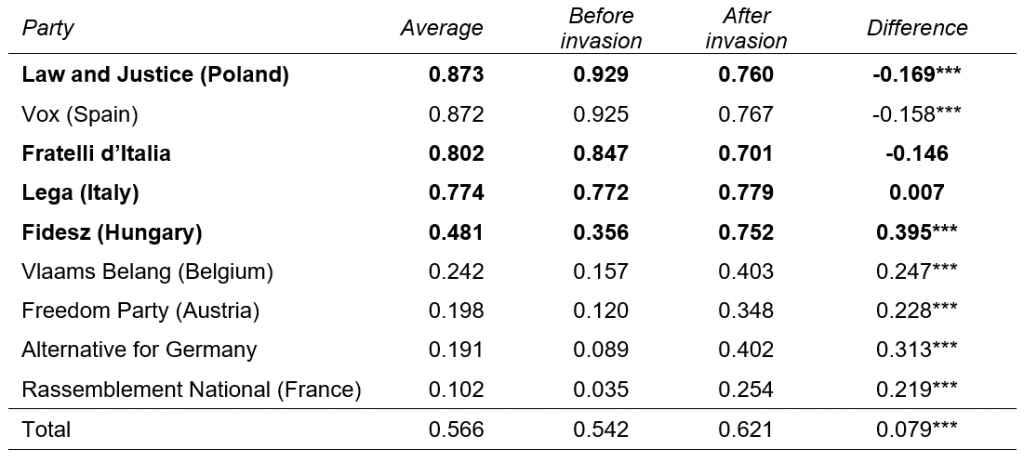

While this division over Russia in the European far right and within the new Italian government appears evident, does it withhold empirical scrutiny? One way to check this is to look beyond the words of the party leaders and assess how they actually vote on relations with Russia. This gives some indication of whether it is feasible for the far right to unite or whether different views toward Putin are likely to make this impossible.

Drawing on work by Hix et al. and VoteWatch Europe, we have developed an original measure of ‘assertiveness towards Russia’. We use all available roll call votes in the European Parliament from the beginning of the ninth parliamentary term in July 2019 until 9 June 2022. From over 13,000 votes, including final votes on resolutions and individual votes on paragraphs and amendments (including split votes when relevant), we selected votes related to assertiveness towards Russia. In our analysis, we differentiate between votes before and after the Russian invasion of Ukraine on 24 February 2022 to spot the changes between the far-right parties, particularly the three far-right governments.

From their political statements, we would expect members of Fratelli d’Italia to be the most hawkish on Russia besides Law and Justice. On the other side, Fidesz and the Lega should be the most Russia-friendly. Besides that, we would expect all four actors to strengthen their positions after the invasion.

However, the data unveils a different picture. Most of those examined had a critical stance toward Russia before the attack. Fratelli d’Italia was closely behind Law and Justice in this respect, but the stand of the Lega was more hawkish than expected before the war, while Fidesz was in the middle of the scale. Among the large far-right players, Marine Le Pen’s Rassemblement National was the most Russia-friendly party before the war. After the invasion, Fratelli d’Italia, similar to Law and Justice, slightly decreased their assertiveness (although this difference was not statistically significant), while the Lega and Fidesz became more critical, even surpassing Fratelli d’Italia.

Table 1: Critical stances against Russia in the European Parliament before and after the invasion of Ukraine (roll call votes, July 2019 – June 2022)

Note: The table indicates the extent to which members of each party voted for stances critical of Russia (or against stances favourable to Russia) in the European Parliament. Such votes were assigned a value of 1, while abstentions and votes against a critical stance (or for a position favourable to Russia) were assigned a value of 0. A higher value in the table therefore indicates members of that party were more likely to vote for stances critical of Russia or against stances favourable to Russia. Paired t-test significance: *0.05, **0.01, ***0.001. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on VoteWatch EU data.

Although other far-right parties such as the Rassemblement National became more critical of Russia following the invasion, they still had a broadly pro-Russian stance. These results suggest Italy should not be an obstacle when voting for sanctions against Russia. Indeed, the question of anti-Putinism could instead unify the governing far-right parties and put them in contrast to other parties like the Rassemblement National, making a further unification of the European far right difficult, despite the observed convergence after the invasion of Ukraine.

Democratic backsliding

We have also examined what to expect from the new Italian governing parties with respect to the rule of law issue surrounding Fidesz and Law and Justice. During a European Parliament debate in September 2022 about Hungary no longer being a fully-fledged democracy, Meloni condemned “using the question of the rule of law as an ideological club to hit those considered not aligned”. She also mentioned that the EU is pushing Orbán closer to Putin.

The dynamics of European Parliament voting are, of course, different from the decision-making process in the European Council, in which Meloni will now take Mario Draghi’s place. Nonetheless, a glimpse at how these parties voted in the European Parliament on rule of law issues offers some useful insights.

Table 2: Defence of the rule of law by party membership in the European Parliament (roll call votes, July 2019 – June 2022)

Note: The table indicates the extent to which members of each party voted to protect the rule of law in the European Parliament. Such votes were assigned a value of 1, while abstentions and votes against were assigned a value of 0. A higher value in the table therefore indicates members of that party were more likely to vote to defend the rule of law. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on VoteWatch EU data.

Our results confirm previous academic findings that parties with traditional-authoritarian-nationalist ideological positions do not defend the rule of law. Unsurprisingly, Law and Justice and Fidesz stand out as among the least likely to defend the rule of law, while the Lega usually votes similarly to these parties.

On the other hand, Fratelli d’Italia is the party with the highest number of votes in favour of the rule of law, even if the differences are minor and largely inconsequential compared to the other liberal parties in the European Parliament. Fratelli d’Italia MEPs voted in defence of the rule of law fewer than one out of every six occasions (17.6%), compared to only 5% among Fidesz MEPs. In light of these results, we would expect the new government in Italy to be a key ally of the Hungarian-Polish backsliding coalition.

There are three key takeaways from this research. First, regarding their position on Russia, the two main parties in Italy’s future government – Fratelli d’Italia and the Lega – might have more in common than is usually assumed. Second, assertiveness towards Russia is still a divisive issue for the broader far-right coalition in the EU. And finally, the governments in Budapest and Warsaw might just have secured an important ally in Italy when it comes to the rule of law issue, with the new Italian government being unlikely to oppose future moves toward democratic backsliding.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Presidenza della Repubblica

It’s interesting to notice such a discrepancy between Fratelli d’Italia ‘s foreign stance regarding Russia and their European stance concerning Fidesz and PiS. Meloni seems keen on reaffirming Italy’s position within NATO but not it’s position within the liberal-democratic sphere of the EU.