The war between Russia and Ukraine has had a major impact on European politics, but how has it affected public opinion? Using data from the European Social Survey, Margaryta Klymak and Tim Vlandas find the war has increased trust in politics in Europe, strengthened support for democracy and freedom, and fostered positive views of immigration and redistribution.

Russia launched a full-scale war against Ukraine on 24 February 2022, which has been condemned by numerous countries and international organisations, such as NATO, the United Nations and the European institutions. The invasion has led to substantial casualties in Ukraine, likely in the tens of thousands, including many children, and brought about the destruction of schools, hospitals and other civilian infrastructure across the country, including key energy and water utilities. Millions have been internally displaced and fled the country in search of safety.

European governments have been at the forefront of the military and humanitarian support to Ukraine since the war began. There are nearly 7.9 million refugees across Europe, while around 4.8 million were registered for temporary protection (or similar national protection schemes) as of December 2022.

In recent research, we explore whether and how public opinion in Europe has changed after the Russian invasion. In a recent Nuffield Politics working paper, we focus on the effect of the invasion on trust in politicians and political parties, and satisfaction with and support for democracy. Our second working paper covers a wider range of attitudes and views about democracy and authoritarianism, immigration, and European integration, as well as redistribution preferences.

Our analyses are based on the recently released tenth wave of the European Social Survey. The survey selects respondents in advance and does not change the pre-agreed interview dates in response to events. We compare respondents that were interviewed just before (control group) and right after (treatment group) the invasion began. We therefore focus on the eight countries where respondents were interviewed both before and after 24 February 2022: Italy, Greece, Portugal, Norway, Switzerland, Montenegro, North Macedonia and the Netherlands (more information about the method and robustness checks can be found here and here). Our findings are shown in Figures 1 and 2.

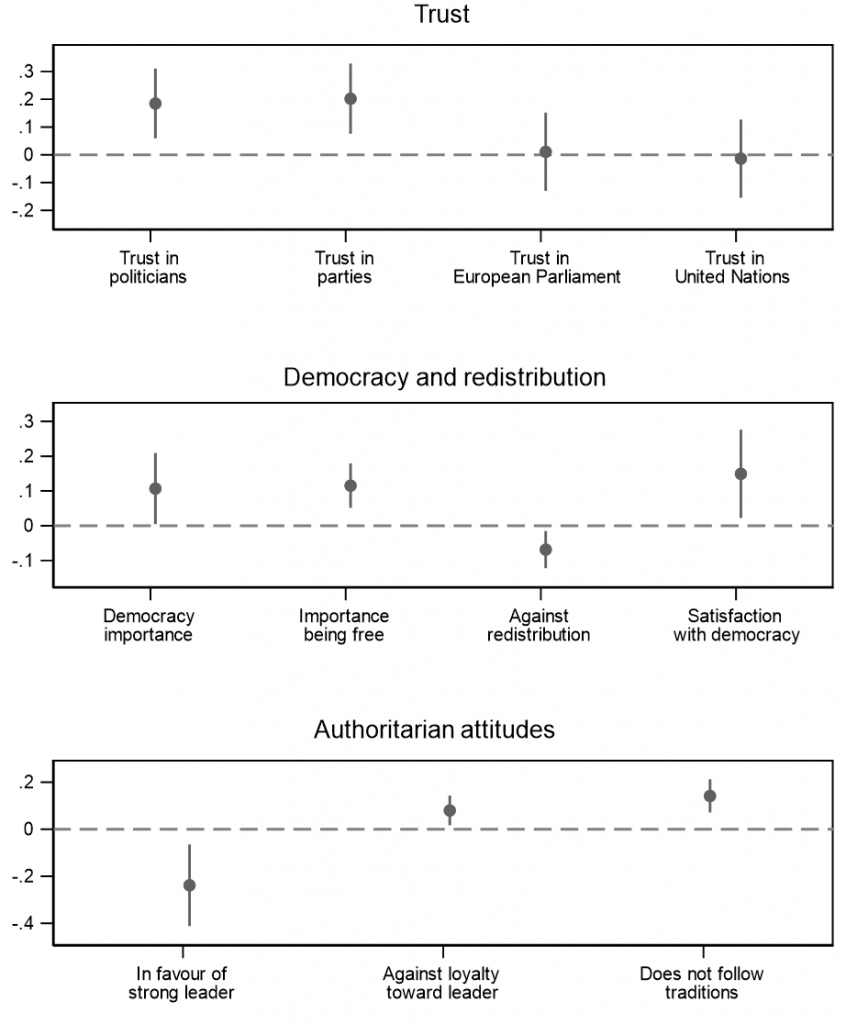

Figure 1 plots coefficients capturing the effect of the Russian invasion on trust, democratic and redistribution attitudes. First, we find the Russian invasion increased respondents’ trust in politicians and political parties but not in the European Parliament or the United Nations (top panel). Second, the war appears to have raised satisfaction with democracy and made people attach more importance to democracy as well as to being free (middle panel). In addition, solidarity was reinforced as captured by respondents’ lower opposition to redistribution. Third, respondents were less favourable to strong leaders and more likely to be against loyalty towards their leader as well as to not follow traditions (bottom panel).

Figure 1: The effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on European trust, democratic and authoritarian attitudes

Notes: Each dot represents a coefficient from different regressions of a dependent variable on a dummy variable taking the value one if a respondent was interviewed after the invasion began, and zero otherwise, as well as a range of controls. The lines around each dot represent the confidence intervals around the effect, which were calculated using robust standard errors. When these lines do not overlap with the zero-line, this indicates that there is a statistically significant effect of the invasion on the particular attitude under consideration.

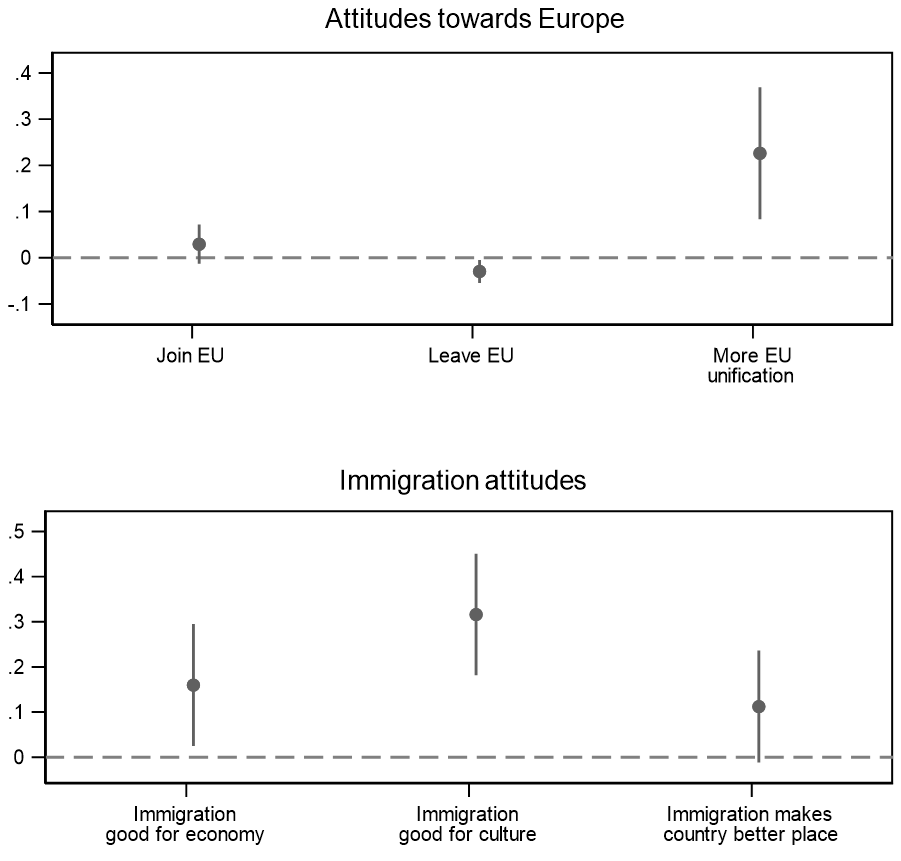

Moreover, the war made respondents of current EU member states less supportive of leaving the EU, while it had no effect on the views of non-EU respondents elsewhere about joining the EU. Respondents also appeared more supportive of European integration (top panel of Figure 2). Finally, the invasion has also changed views on immigration’s impact on a country (bottom panel of Figure 2): respondents surveyed within fourteen days of the start of the war had more positive views of the impact of immigration on a country’s culture and economy, and were more likely to declare that it makes their country a better place to live.

Figure 2: The effect of the Russian invasion of Ukraine on European trust, democratic and authoritarian attitudes

Notes: Each dot represents a coefficient from different regressions of a dependent variable on a dummy variable taking the value one if a respondent was interviewed after the invasion began, and zero otherwise, as well as a range of controls. The lines around each dot represent the confidence intervals around the effect, which were calculated using robust standard errors. When these lines do not overlap with the zero-line, this indicates that there is a statistically significant effect of the invasion on the particular attitude under consideration.

Overall, Russia’s invasion of Ukraine has increased trust in politics, strengthened support for democracy and freedom, and fostered positive views of immigration and redistribution in Europe. Going forward, whether European public opinion holds up in the medium term may prove crucial if European governments are to continue supporting Ukraine and its citizens.

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: European Union

I am not convinced. Latest polls in Germany suggest that confidence in the EU is low and, with regards to German institutions, falling to an historic low