Over the last decade, several far-right parties in Europe have expressed support for Vladimir Putin’s regime in Russia. But has this support changed following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine? Drawing on a new study, Adam Holesch and Piotr Zagórski show the invasion has triggered a significant shift among Europe’s far-right parties in their approach toward Russia.

The Russian invasion of Ukraine in 2022 served as a wake-up call for the EU to guard against authoritarian influence. In a new study, we show that the European far-right has not been immune to the fallout. Indeed, after the invasion, Putin’s regime became a toxic association for populist radical right parties.

This stands in stark contrast to the 2010s, a time when the far-right played directly into Putin’s hands. Parties like France’s National Front (now Rassemblement National – RN), Austria’s FPÖ, and Germany’s AfD propagated Russia’s anti-democratic and illiberal narratives. Viktor Orbán’s regime in Hungary was even seen as Putin’s ‘Trojan horse’ in the EU. In the European Parliament, most populist radical right parties aligned with Russian interests, with the former ENF group consistently supporting Putin. The rest of Europe, for the most part, remained indifferent, as Putin sympathisers found their way into various left and right-leaning parties.

However, there were notable exceptions to this trend. In 2015, the Polish Law and Justice (PiS) party rose to power, articulating an anti-Putin stance as part of its ideology. In 2022, other far-right players followed suit. Georgia Meloni and her Fratelli d’Italia party strongly criticised Russia during their electoral campaign, aiming to distance themselves from Matteo Salvini’s Lega, who had previously expressed admiration for Putin. This latest division in the populist radical right stance against Russia emerged simultaneously with a new unification effort by the far-right.

In the summer of 2021, populist radical right leaders signed a document in several European capitals, calling for a deep reform of the EU. Networking events in Warsaw (December 2021) and Madrid (January 2022) followed, attended by most signatories, though the Finns Party and the Danish People’s Party were absent. While it’s challenging to pinpoint a clear initiator of this effort, the Polish PiS and Hungarian Fidesz, both democratic backsliders in the EU, undeniably played a significant role. However, they themselves were divided over Russia, disagreeing on critical matters such as Russian sanctions and aid for Ukraine.

In our study, we analysed over 13,000 Roll Call Votes (RCVs) in the European Parliament from July 2019 to June 2022 to assess changes in the ‘assertiveness towards Russia’ of populist radical right parties. By comparing votes before and after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, we aimed to identify any shifts among the involved actors. We selected parties that participated in the Warsaw and Madrid summits and had at least three MEPs, excluding some populist radical right parties from Bulgaria, Estonia, Lithuania, Poland, and Romania with only 1 or 2 MEPs. Additionally, we included the German AfD, which still operates widely outside this network.

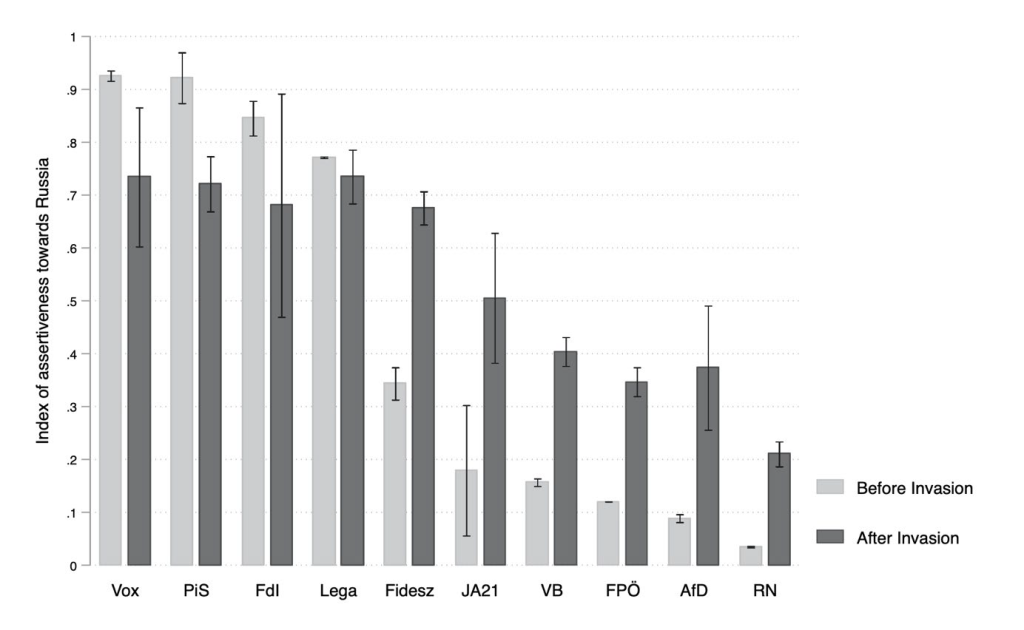

Figure 1: Assertiveness towards Russia before and after the invasion of Ukraine by party membership

Note: The figure shows European Parliament Roll Call Votes between July 2019 and June 2022. Source: Authors’ own elaboration based on VoteWatch EU data.

As depicted in Figure 1, the MEPs belonging to populist radical right parties exhibited significant variations in their views on Russia prior to the invasion. This division spanned from highly assertive positions held by Vox, PiS, and Fratelli d’Italia, with mean scores of 0.92, 0.92, and 0.84 respectively on a scale of 0-1 (where 1 represents full assertiveness towards Russia). On the other end of the spectrum, MEPs from the FPÖ, AfD, and RN displayed greater compliance with Russian interests, with mean scores of 0.12, 0.09, and 0.03 respectively. Notably, Fidesz emerged as the most assertive among the less assertive group of parties, garnering a mean score of 0.33.

Although the mean assertiveness of MEPs belonging to populist radical right parties showed only a slight and statistically insignificant increase from 0.53 to 0.57 before and after the invasion, respectively, significant differences in positions emerged among individual parties. Notably, the assertiveness of PiS and Vox decreased, while Fidesz’s assertiveness more than doubled (from 0.33 to 0.67) after the invasion.

These findings are surprising, as one might expect a divergence in assertiveness towards Russia among these parties. Unexpectedly, the Russian invasion appears to have brought PiS and Fidesz closer together. Orbán’s portrayal as Russia’s EU ally contrasts with the unclear position of Fidesz. Similar trends are observed among other populist radical right parties analysed in this study, with the German AfD displaying increased assertiveness towards Russia post-invasion. Overall, the Russian invasion has diminished the pre-existing differences among EU far-right parties regarding their stance towards Moscow.

As we delve into other aspects of the analysis, intriguing revelations emerge. The Spanish party VOX emerges as the boldest and most assertive, potentially driven by their desire to counter the pro-Russia stance of the Spanish far-left, at least prior to the invasion. Surprising is also the position of Italy’s Lega, considering their leader, Matteo Salvini, once sported a Putin shirt in Moscow. Meanwhile, the French RN and its leader Marine Le Pen appear to maintain a favourable stance towards Putin.

In conclusion, the issue of assertiveness towards Russia keeps the populist radical right parties at odds, even as they become more critical of Putin. The Russian invasion of 2022 dealt a severe blow to Russia’s influence among these parties, shattering their previous support. As a result, Putin’s regime became toxic, further complicating the prospects of far-right unification.

For more information, see the authors’ accompanying paper in West European Politics

Note: This article gives the views of the authors, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Сергей Карпухин, ТАСС / kremlin.ru