Although the Polish left looks set to return to government after 18 years, its vote share decreased in last month’s election and it risks being subsumed within a coalition dominated by more economically liberal and socially conservative groups, writes Aleks Szczerbiak.

In recent years, the Polish left has enjoyed considerable influence on public debate. Many of its policy stances on both socio-economic and moral-cultural issues now enjoy widespread support and have been adopted by more liberal and centrist political groupings. However, this has not been matched by electoral success.

For much of the post-1989 period, the most powerful political force on the left was the communist successor Democratic Left Alliance (SLD), which governed Poland from 1993-97 and 2001-5. However, the Alliance’s support collapsed at the 2005 parliamentary election following a series of spectacular high level corruption scandals.

It contested the 2015 election as part of the United Left (ZL) coalition but narrowly failed to cross the 8% parliamentary representation threshold for electoral alliances (5% for individual parties). As a result, left-wing parties did not secure parliamentary representation for the first time since 1989.

The Alliance faced a challenge on its radical left flank from the Together (Razem) party, which gained kudos among many younger, left-leaning Poles for its dynamism and programmatic clarity. It accused the Alliance of betraying left-wing ideas by pursuing orthodox liberal economic policies when in office.

In the event, Together won 3.6% of the vote in 2015, which was not enough to obtain parliamentary representation but meant that it peeled away sufficient left-wing votes to prevent the United Left from crossing the 8% threshold. However, Together failed to capitalise on its early promise and attract a broader range of support beyond the well-educated urban “hipsters” that formed its core electorate.

In 2019, another left-wing challenger party emerged in the form of the social liberal Spring (Wiosna) grouping formed by veteran sexual minorities campaigner Robert Biedroń, at the time the Polish left’s most popular and charismatic politician. However, after a promising start, Spring struggled to carve out a niche for itself and only just crossed the 5% threshold in that year’s European Parliament election, well below expectations.

Consequently, these three parties contested the 2019 legislative election as a united Left (Lewica) slate and finished third with 12.6% of the vote, regaining parliamentary representation for the left after a four-year hiatus. Many left-wing activists and commentators hoped that the new Left parliamentary caucus would use this platform to shift the terms of the debate decisively to the left and challenge the right-wing and liberal-centrist duopoly that has dominated Polish politics since 2005. The Democratic Left Alliance changed its name to the New Left (Nowa Lewica) and merged with Spring, although Together chose to maintain its organisational independence and distinctive ideological identity.

In fact, last month’s parliamentary election results were bittersweet for the Left. On the one hand, opposition parties won enough seats to secure a parliamentary majority and it looks set to become the first left-wing grouping to join a Polish government for 18 years. On the other hand, the Left lost half-a-million voters as its vote share fell to 8.6%, which translated into only 26 seats in the 460-member Sejm, Poland’s more powerful lower parliamentary chamber. This was 23 fewer than in 2019, making it only the fourth largest parliamentary grouping. This means the Left will return to office as the smallest member of a governing coalition dominated by liberal- and agrarian-centrist parties.

Lacking a distinctive appeal

So why did the Left perform so badly? Firstly, its election campaign often came across as dull and unimaginative, with even politically sympathetic commentators acknowledging that it lacked emotional impact and a strong and clear over-arching narrative about what the grouping stood for and how it would govern differently from other parties.

Indeed, during much of the campaign, the Left behaved as if its overriding priority was simply to work with other opposition parties and remove the right-wing Law and Justice (PiS) grouping, Poland’s governing party since 2015, from office. This encouraged many of its potential supporters to switch to the larger liberal-centrist Civic Platform (PO), Poland’s ruling party between 2007-15 and subsequently the main opposition grouping. Put simply, the Left did not do enough to stress its distinctiveness as an independent political actor, particularly given that over the last few years Civic Platform has pivoted strongly to the left on both socio-economic and moral-cultural issues.

The fact the Left focused much of its fire on the smaller radical right free-market Confederation (Konfederacja) grouping also helped create the sense that it was competing for voters on the periphery rather than at the core of the Polish party system. Indeed, the Left appearing to acknowledge that it would only be a junior partner in a future anti-Law and Justice government also had a de-mobilising effect on its potential supporters, which even the most effective political marketing would have had difficulty overcoming.

An exit poll conducted for the Ipsos agency found that only 57.6% of 2019 Left voters stuck with the grouping in 2023, while 23.8% switched to Civic Platform (which secured 30.7% support overall and 157 seats) and a further 12.9% to the Third Way (Trzecia Droga), an agrarian- and liberal-centrist electoral coalition (which also finished ahead of the Left with 14.4% and 65 seats).

Not winning enough younger women, losing older voters

The Left had hoped to tap into the political mobilisation generated by the huge demonstrations that erupted in October 2020 when Poland’s constitutional tribunal ruled that abortions in cases of foetal defects were unconstitutional. Poland already had one of Europe’s most restrictive abortion laws and the tribunal’s ruling meant that the procedure was legal only in cases where pregnancy put the life or health of the mother in danger or if it resulted from incest or rape.

The abortion protests were among the largest in Poland since 1989. Many young Poles were no doubt attracted by their carnival atmosphere at a time when the scope for social interaction was severely limited by pandemic restrictions, but some commentators also argued that they were a formative political experience for those who participated in them, particularly younger women.

However, although several of the Left’s leading figures were at the forefront of these protests, they did not appear to provide the grouping with an electoral boost. While the Left secured an above-average vote share of 10.1% among women (compared to 6.9% among men) this was considerably less than it was hoping for given how much of its campaign messaging was focused on trying to attract female voters.

The Left did attempt, to some extent at least, to showcase some its most effective female leaders who promoted the grouping’s policy promises on issues such as liberalising the abortion law. The Left was, for example, the only political grouping to be represented by a woman, Joanna Scheuring-Wielgus, during the sole televised party leaders’ debate.

However, for a political formation that professed to be in favour of increasing women’s representation (by mandatory quotas if necessary) it foregrounded male politicians during many of the most high-profile campaign moments. For example, it was New Left joint leaders Biedroń and veteran ex-communist Włodzimierz Czarzasty who spoke on the main platform during the opposition’s huge March of a Million Hearts (Marsz Milion Serc) in Warsaw two weeks prior to the election.

For sure, the Left secured the support of 17.7% of under-30s, among whom there was also a huge increase in turnout, the second highest vote share after Civic Platform on 28.3%. But this was the same proportion that the grouping won in 2019 and, again, it was hoping for considerably more, particularly given that in 2020 the CBOS polling agency found that the number of Poles aged 18-24 who identified with the political left had nearly doubled from 17% in 2019 to 30% in 2020 (the highest number recorded since the collapse of communism), rising to 40% among young women.

However, particularly disappointing for the Left was the massive defeat that it suffered among older voters: it only secured 5.1% of 50-59-year-olds and 5.2% among over-60s. For years, this demographic had comprised one of the Polish left’s most important electoral constituencies, especially the (admittedly declining) section of the electorate that had some positive sentiments towards, or direct material interests linking them to, the previous communist regime, such as those families who were connected to the military and former security services.

Responsibility without influence?

Moreover, although the 26 Left deputies are theoretically indispensable to a future government formed by the current opposition parties, the grouping risks being subsumed within an administration dominated by larger centrist parties whose instincts are more economically liberal or socially conservative – and, therefore, the Left will be unable to implement its flagship policies.

For example, the expected new government’s preliminary coalition agreement lacked a specific pledge to liberalise the abortion law in line with the Left’s programme because the Polish Peasant Party (PSL), the moderately socially conservative grouping that makes up one-half of the Third Way, made it clear they oppose this. The Left really needs to carve out a niche for itself by securing control of ministerial portfolios where it can make an impact either by advancing its political agenda on moral-cultural issues or where its socio-economic policy pledges are not reined in by overall government budget constraints.

In fact, the Left is divided on how to operate most effectively in the new parliament. While politicians from the more centrist New Left will take up government ministerial positions, the seven deputies who represent Together have decided not to formally join the coalition having failed to secure firm pledges on abortion and financial guarantees for the implementation of its social policy programmes in areas such as health care and housing.

However, Together has said that it will vote to install the new government in a forthcoming parliamentary confidence vote. The problem with this approach is that it risks leaving Left supporters feeling their votes have been wasted while, at the same time, Together is propping up – and, therefore, still being held responsible for (while having even less influence upon) – the new government.

A strategic dilemma

Even if the Left can finesse this and carve out a distinctive role for itself within the new administration, it still faces a long-term strategic dilemma. Many more Poles declare their attachment to left-wing views (around 20% according to 2020 CBOS data) than vote for the Left.

However, in Poland declarations of left-right self-placement are generally determined by attitudes towards moral-cultural issues rather than traditional left-wing socio-economic concerns. Indeed, less well-off, economically leftist voters tend to be more socially conservative, so often incline towards parties such as Law and Justice that are right-wing on moral-cultural issues but also support high levels of social welfare and greater state intervention in the economy.

For example, only 5.1% of workers voted for the Left (its highest vote share, 21.9%, was among students) while 50.4% supported Law and Justice. Although the Left did include social programmes in its election platform, for most Poles it was associated primarily with moral-cultural rather than socio-economic issues.

At the same time, in Poland the younger, better-off, socially liberal voters who in western Europe would incline naturally towards left-wing parties are often also quite economically liberal. There is always a risk that these voters will support larger liberal-centrist groupings such as Civic Platform, particularly if they (as many of them did in this election) prioritise keeping Law and Justice out of office above all else.

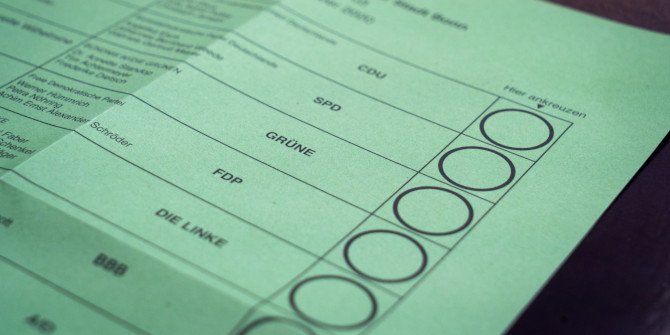

Note: This article first appeared at Aleks Szczerbiak’s personal blog. It gives the views of the author, not the position of EUROPP – European Politics and Policy or the London School of Economics. Featured image credit: Grand Warszawski/Shutterstock.com

This is a good overview of what happened to the Left in the October 15 general election, but there are some observations to be added. Firstly, the threshold for the Left’s entry to the Sejm was 5%, since its committee was registered as a party, whereas Third Way (i.e. PSL + Polska 2050) was registered as a coalition, needing to get over 8% of the vote. In the final week of the campaign, polls suggested that New Left would get 5% comfortably, but Third Way was iffy. If either committee failed to get over the threshold, PiS would have had a majority again. Thus, many people voted for Hołownia and Kosiniak-Kamysz’s Third Way just to make sure they got in.

Secondly, many former Left politicians have joined the Civic Coalition (KO) committee, either with their own small group (Inicjatywa Polska, the Green Party), or joined the Civic Platform (PO) outright (e.g. Arłukowicz). Even though PO is still called a right-of-centre party and belongs to the EPP Group in the European Parliament, the Civic Coalition is far to the left of where PO was, say, around 2007. Barbara Nowacka, who led the Left Alliance in 2015, and former SLD spokesman Dariusz Jonski, along with other ex-Left politicians, comprise the small but influential Polish Initiative (IP); both have been very prominent in the media in the last few years, and Barbara Nowacka got the fourth highest vote on Oct. 15, the highest for a woman in the nation. She is slated to become Minister of Education, a vindication of her inadequate debate performance in 2015 and the resulting PiS victory. Jonski is half of the Szczeba-Jonski team which has uncovered so many PiS scandals using the tool of a parliamentary investigation/audit.

Thirdly, the Left leadership is a bit questionable. Czarzasty is an old SLD warhorse who treats rivals rather like Donald Tusk and Jarosław Kaczyński, i.e. brutally, although he gave an excellent speech at the Oct. 1 March of a Million Hearts, and has undeniable skills. Biedroń, the gay rights activist who greatly enhanced his reputation as Mayor of the city of Słupsk, was elected to the European Parliament in 2019 and has somewhat tarnished his reputation and been absent in Brussels, while Together’s charismatic Adrian Zandberg has not displayed great capacity for working as part of a coalition or team and reassuring voters that he is not a Bolshevik incarnate.

On the other hand, the Left did surprisingly well in the Senate, and in both the Sejm and the Senate, the New Left has elected a number of really outstanding women (as did Civic Coalition and Third Way).

The net effect is that the new coalition majority has a large number of young, left-oriented members of the Sejm. I am a little concerned that some of them, especially the women, are enthusiastically and perhaps naively pushing socially “progressive” ideas, especially LGBT+ rights, at a time when the West is starting to discover the illiberal nature of Wokism, especially the corrosive impact of trans rights activists and the shackles of political correctness on free speech. While the conservative elements in Third Way may hold back progress where it is really needed, namely, on abortion rights, everybody may be too unfamiliar with the subject and with what has happened in the Anglosphere to restrain the excesses of Woke activists. This will provide much fuel for PiS, Confederation and the Polish Church (in effective schism from Francis’ Rome) to agitate the moral-cultural (“obyczajowy”) cauldron.