This contribution offers intimate insights on entering the field, establishing relationships with research participants and the use of visual methods to gather material. It builds on my work on the coexistence between the old and the new in Shanghai, spanning across multiple scales: from the structural forces that trigger and direct globalisation, migration and urban change to the processes of agency, which become manifest in individual perception, attitude and behaviour. The speed and scale of China’s urban transformation require not only the continuous questioning of established theories, but also the creative use of unconventional methods to capture ephemeral conditions, writes Deljana Iossifova.

This contribution builds on my previous doctoral research, Lives on the Borderland: The Sociospatial Transition of a Neighbourhood in Shanghai. Coming from an architecture background, I had practiced in China for several years before beginning my work on the PhD. I knew what I was interested in – the curious phenomenon of coexistence of and the human experience of transformation in in-between spaces that emerge when parts of the existing city are erased and replaced with new residential developments and their respective residents. In retrospect, it is safe to say that I entered the field blissfully, ignorant of basic theoretical approaches or research methods in social sciences. I had yet to invent my methods of data collection, and learn how to analyse my data and relate my analysis to the extant literature. This is an arguably difficult position to start from, but it left me advantageously unbiased and open to experimentation.

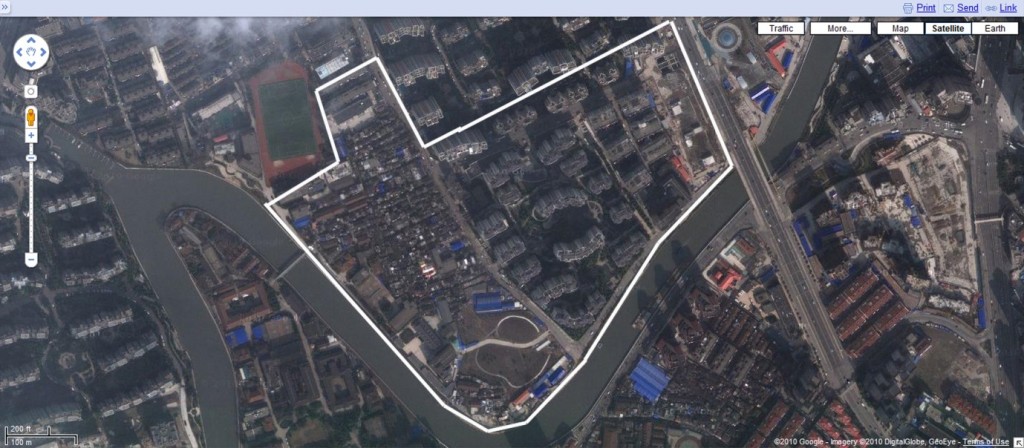

In early 2007, my fieldwork began with the task of identifying a suitable case study area. I chose an area north of Shanghai’s Suzhou Creek and west of the inner city. Here, there were two very different neighbourhoods adjacent to each other, separated only by a narrow street (see Figure 1). On one side, there was the remainder of a former slum; on the other, a new-build residential development – a typical gated residential compound. My work in the field included the visual and sociometrical cataloguing of interactions across the street between these two adjacent areas. It also included an inquiry into what people had to say about one another and about the borderland between them. In the following sections, I elaborate on participant photography and photo elicitation interviewing, which I used extensively to generate the data. I have added excerpts from my original field notes and hope that – without the need for too much further explanation – these reflect both the advantages and challenges of using a visual method by an inexperienced researcher in Shanghai.

It felt natural to begin my work in the field with systematic visual exploration of the site. Using a randomly spaced grid upon an aerial of the case study area to guide me, I set out to photograph each of the grid points in order to establish a rich digital database of photographs which I would later use in photo elicitation interviews. The residents and workers I came across in the process were usually very curious as to who I was and what I was doing; this made it easy to follow-up with interview requests. However, people easily withdrew as soon as it came to filling in formal questionnaires, let alone signing informed consent forms. Many simply could not read; others feared officials might be able to track them down, regardless of my reassurance that all data would be treated with utmost care and that, of course, they would remain anonymous. In order to avoid any risk of causing harm to them, I retreated to merely requesting verbal consent and used pseudonyms for each person from start to finish.

I take photos [in the old part of the study site]. I am suddenly surrounded by several people: a few young guys, an older man […] and a family of three – a young woman, a young man and their little daughter. Everybody wants to know what I am doing, so I show them the map and point at where we are right now, trying to explain that I am taking a picture at every point of the grid. […] She hands it back to me: ‘我不能读’, she says – ‘I cannot read’. As she turns around and disappears inside the little house, I am watching her, my mind working to decide whether this could possibly be true, or if they just want to get rid of me.

As I began to get to know the people in the study area, it became clear that many were rural-to-urban migrants who spoke their own dialects and that I would need substantial help if I wanted to communicate with them successfully. I was fortunate that Jaye Shen, my former Mandarin teacher with a degree in Psychology, agreed to become my research companion and help me to conduct over twenty open-ended, in-depth interviews with residents on the site. She also helped me to work through the realisation that seemingly unimportant matters would affect my perceptions and interactions with people, particularly where their lived realities were significantly different from mine. For instance, it was impossible to ignore that their everyday included casual practices developed to rid themselves of rats, cockroaches and other nuisances, whereas I seemed unable to rid myself of irrational feelings of fear and disgust. It took time and considerable effort to ignore how my body (and mind) reacted to common conditions; however, I cannot begin to describe how grateful I am to the people I worked with for the generosity and understanding they showed.

We are late about an hour for our appointment with Ms Ye. […] She appears from somewhere but seems very busy and asks us to join her upstairs. We follow her to the balcony, where she folds the laundry whilst complaining about the bad living conditions and how much better off people are when they live in modern high-rise buildings. I say that I live in one of those high-rise buildings; that it rains into the rooms there, too, and that it is cold in the winter and hot in the summer. But the moment I say these things out loud I feel stupid. We go back inside. […] We sit on the floor and watch Ms Ye make the bed. The room is clean; there is a night pot next to the running computer. I dare to ask Jaye if she thinks that there might be cockroaches in the house; she laughs at me in response. I feel ignorant, again. Ms Ye looks at us as if she is unsure about what to do with us; then tells us to go downstairs and start the interview with her parents. There, we are offered food and drink, and we have to eat as we speak. I try not to look, but as I place food in my mouth and pretend to focus on my notes, I see the cockroaches. Everywhere. On the table; on the bed; on the floor; and climbing up my stool. I pick up my bag and hold on to it for the rest the interview, angry at myself for my feelings.

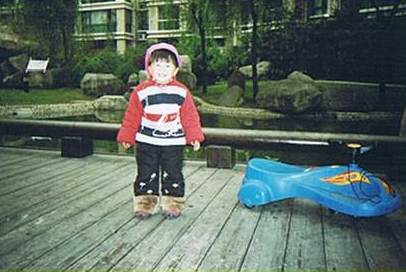

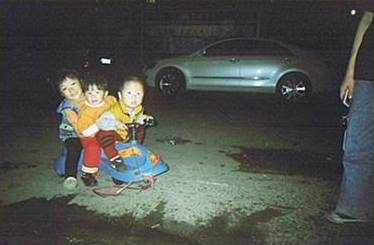

Most of the in-depth interviews we conducted were based on photographic materials: my own and the photographs taken by participants. In a lengthy (and not always successful) process, we had distributed a choice of analogue and disposable cameras among residents on both sides of the borderland and asked them to photograph the things, places and people that they regarded as generally important for their lives. I tried to keep instructions as vague as possible in order to give photographers the freedom to think about and choose what, where and who was important to them. Once equipped with their cameras, they had between several hours and several weeks to complete the task. Then I would meet with them to collect the films or cameras and schedule an appointment for a follow-up interview, when we would invite them to speak about the stories behind their photographs, their importance and meaning. With a few exceptions, participants could easily be recruited as they were generally excited about the opportunity to do something fun and creative, something that would let them break away from their everyday routines; equally, they often felt thrilled about the chance to speak openly and in-depth about matters so close to their hearts. They always received a copy of their photographs, and during interviews, we took great care to discuss with them which photographs I would be allowed to use in presentations, publications and other outputs later on.

Mr Hu appears from the house next door, holding a sizzling wok in one hand and waving at me with the other. He knows me now, we talk. I explain the purpose of the photo elicitation exercise, he seems to understand. Finally, he takes the camera and tells me to come back later that day to collect the film. As we speak, I see a crowd forming around us, twenty to thirty people staring at us and listening in. ‘I would like to participate, too’, one says, and I gladly hand him another camera. Others follow, and we make appointments when to meet again. [A few weeks later, we] walk into the alley and Mr Hu appears immediately. Mr Hu lights a cigarette and disposes of the ashes on the floor. I hand him a package containing [his photographs]. He begins flipping through them and seems very happy. Then he starts talking.

They started demolition in 2004. Most of the neighbours have moved away. Garbage is all over the place now. Nobody takes care of it. It is hard to keep the dog from eating garbage. (Mr. Hu)

It hurts me to see my son do this in midst all the garbage and debris. Different from the people in the gated residential compound across the street who have big playgrounds, my son has to go and rent a basketball court with his friends, and we would have to pay by the hour (Mr. Hu)

![Mr Hu cooking dinner in his kitchen/living room. Mr Hu: ‘This room used to be the bedroom for my parents, now it's the living room for my family – we cook here, eat, do the laundry. Everything. Over there [pointing at the gated residential compound], they have an extra room for everything. This is how it should be’. Photograph: Mr Hu, April 2007](https://blogs.lse.ac.uk/fieldresearch/files/2013/11/Iossifova-Fig4.jpg)

This room used to be the bedroom for my parents, now it’s the living room for my family – we cook here, eat, do the laundry. Everything. Over there [pointing at the gated residential compound], they have an extra room for everything. This is how it should be. (Mr. Hu)

When we arrive across the street from Ms Lu’s shop [after six months], I feel my stomach cramping up in expectation. Will we find them? We sit down for a while to absorb what is happening. I am shocked at first because everything seems to have changed. The shops are gone. In their place we find three small restaurants, very new and well frequented. I am worried, but then I see the Ms Lu’s little girl. We ask about her mother and she takes us inside the wet market. Ms Lu seems excited, she says she saw us sitting on the other side and it made her laugh: ‘Everything else has changed, but you are still there where you used to sit!’ As an outsider, it feels strange to be the only fixture in the neighbourhood. Her husband joins us and we are asked to follow them to their new ‘house’ – one of the small spaces that line the street, hidden behind a roller shutter. It is much smaller than their previous place, I think, but then again, it is meant for living only, now that they have a proper shop. We are asked to sit down on the tiny stools that magically appear, and Ms Lu’s husband arrives with bottles of cold water shortly after. I give them the package of photographs, and we start talking.

When the security guards know you, it’s not a problem at all to use the park. Any time. It’s a good place for my daughter to play (Ms. Wu)

Two of the neighbourhood kids have been sent back to the countryside by their parents – they had to move during the renovation and are now struggling to find new business. It’s a pity. One of the girls even got a place at the local kindergarten’. Two years later, Ms Lu had to send her own daughter back ‘home’ because she could no longer afford to keep her in the city (Ms. Lu)

Throughout my research, my confidence in any findings from previous stages was vehemently shaken and ultimately eroded by developments on the ground and how they affected the individuals, social groups and spatial territories that I had allowed myself to think of as stable or fixed.

In lieu of a conclusion, let me briefly summarise how visual methods and participant photography have helped me address my research questions. Photography and film are powerful tools that help researchers capture and analyse not only everyday dynamics in urban space, but also long-term patterns of change. The growing visual database that I created over time allowed me to revisit places and identify changes. Although it cannot replace verbal communication, photography can help bridge potential language barriers in that it adds a degree of universal understanding, just as it was the case for me as a non-fluent Mandarin speaker working with people from all walks of life, allowing discovery and clarification. Participant photography engages people in an act of creation, and photo-elicitation interviews often reveal stories, facts and meanings that would otherwise have remained hidden from the understanding of a researcher. Lastly, experience has taught me that photography can be invaluable in the communication of results to very different audiences. In short, the speed and scale of China’s urban transformation require not only the continuous questioning of established theories, but also the creative use of unconventional methods to capture ephemeral conditions.

About the author

Deljana Iossifova is a Lecturer in Architectural Studies at the Manchester Architecture Research Centre (MARC), University of Manchester. She holds a PhD in Public Policy Design from Tokyo Institute of Technology and a diploma in Architecture from the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology (ETH Zurich). Before joining the University of Westminster to work with Jeremy Till on the project Scarcity and Creativity in the Built Environment (SCIBE), she was a PhD/Postdoctoral Fellow at the United Nations University, Institute of Advanced Studies (Sustainable Urban Futures Programme). She has contributed to the Europe China Research and Advice Network (ECRAN) on EU-China relations around urbanisation and sustainability. As an architect, Iossifova has practiced in Europe, the United States and East Asia. Her research interests can be situated on the interface between the social sciences (such as social and environmental psychology, human geography and social anthropology) and professional practice. She holds considerable expertise regarding urban transformation of China with a special focus on migration, co-existence, place-related identity and the experience of sociospatial transformation in Shanghai.

A Note on the Research and Results

As noted, the contribution above builds upon my research for doctoral dissertation (Lives on the Borderland: The sociospatial transition of a neighbourhood in Shanghai), and the project started in October 2006 and was complete in March 2010. The field work and research have led to a number of publications, some of which are listed below:

- Iossifova, D. (2012). Shanghai Borderlands: The Rise of a New Urbanity? In T. Edensor & M. Jayne (Eds.), Urban Theory beyond the West: A World of Cities (pp. 193-206). London and New York: Routledge

- Iossifova, D. (2009). Negotiating Livelihoods in a City of Difference: Narratives of Gentrification in Shanghai. Critical Planning, 16, 98-116

- Iossifova, D. (2009). Blurring the joint line? Urban life on the edge between old and new in Shanghai. Urban Design International, 14, 65-83

2 Comments