In this piece that examines participatory methods with children and young people through an early stage research project, Alice Little describes her experience of engaging with a local community youth group and how it represents the many voices of children and young people engaging in research.

_______________________________________________

Children and young people have been increasingly engaged in research as co-researchers by a variety of academics and community organisations, opening new avenues of enquiry around what it means to co-create research. In 2005, Kellett described how the world of academia would need to explore and potentially broaden its definitions of what was accepted as ‘research’ if child-led research was to be accommodated and valued. Corney et al. (2021) suggest that supporting and facilitating opportunities for young people to participate takes significant resources, including time and mindful reflection, alongside an understanding of the ways young people are often marginalised by the way research is undertaken. This blog examines how early stage research can provide many opportunities for researchers to recognise and acknowledge young people’s attempts to engage with the research process and how participation can be identified as taking on many forms.

Embarking on a PhD examining the impact and efficacy of participatory methods with children and young people, I knew I wanted to explore and begin to understand what it was like for young people to engage with the research process. Often, research starts from an adult point of view, with a research question set or hypothesis to test, so the intention with this initial project was to include the young people at the early stages of the research process. The young people could therefore consider, and make decisions, relating to research questions, and I as an adult researcher could see how this participation shaped the project. Together, through participatory methods, I would try to determine what participation meant for the young people.

As a starting point for this project, I had to provide the University ethics board with an in-depth description of what the research would look like. In the very early stages, an honest description of the research plan meant that the method for collecting data could actually be one of many, that in fact I wanted the young people to decide upon the formulation of research questions and choice of methods right through to the analysis and dissemination of the research. In discussions with the adult youth workers, I decided to begin with a working title of ‘What does community mean to us/what does it mean to be in this place?’, in order to engage the young people in the first instance and be able to show them examples of what research looks like. It is important to note that this was the first experience of research for the young people, the youth workers and myself. Therefore, together with the adult youth workers, I identified that having a topic as a starting point would enable all members of our group to engage and to create a space for discussion.

In this project, time was taken to introduce this idea of research to a group of 14-15 year old young people who had been identified as a social action group within a local community. I decided to use a series of creative activities including mapping activities, photo voice methods and poetry writing, to determine what the young people would like to develop further. I was intending to ask questions about how the young people were participating in the research, and the adult roles surrounding this, through group discussions held on a fortnightly basis. Participatory methods that encourage its participants to become part of the research process, using a mixed method approach to make decisions about the research, have been described as achieving a deeper level of participation.

It was through discussions around the concept of ‘deep participation’ and the potential impact of this, that a research proposal began to form. A discussion identified that young people thought engaging in research could potentially ‘look good on your CV’ or also be ‘something fun to do’.

The initial intention of this research project was to engage with youth workers and young people as co-researchers, to develop a project together. I imagined a year-long project that combined a variety of methods, ways of engaging that would encourage the young people to take ownership and, if appropriate, to guide the project through each stage of the research design. The engagement with the group of young people, after 6 months of community involvement and participation, has raised many questions primarily around voice, participation, and choice in the research process. For example, the first session after the initial introduction provided an opportunity to reflect upon what participation means in regards to choice, as no one arrived to take part in the activities. The adult researcher’s agenda became irrelevant and offered an opportunity to reflect upon how children and young people are able to ‘voice’ their own agendas in many ways. Ben Lohmeyer (2020) suggests how viewing young people as having ‘parallel projects’ when it comes to engaging with research, enables the research process to be discussed and evaluated in terms set by both the adult researcher and the young people. Positioning the young people as researchers from the off was an agenda set by the adults, prompting us to question whether the young people were sufficiently able, at such an early stage in the process, or even interested in engaging with setting a research question.

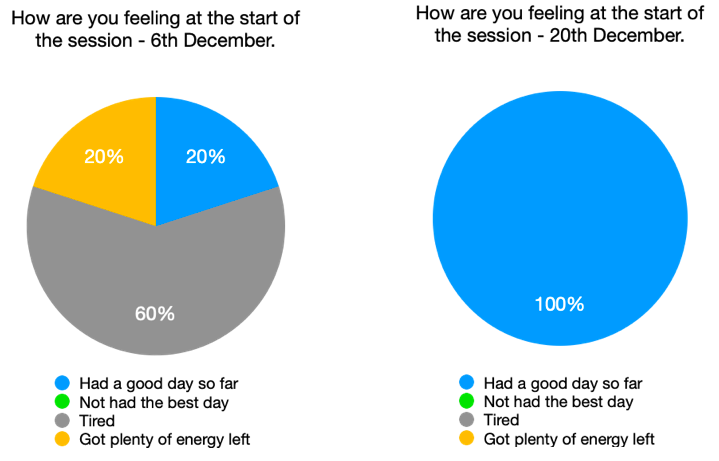

The nature of each interaction within these sessions informs part of the data collection, crucially recognising how participation is fitting into the young people’s lives and about how non-participation and voice are entangled within the definition of choice for the young people. Sessions were generally held after school and often the young people arrived describing their disengagement with school and lack of energy. Looking back on my reflective notes, I see that in the introductory session, before consent was obtained, I have noted that having a check-in style option could potentially alleviate some of the tensions when the young people first arrive. As a novice researcher it took weeks for this to come into fruition, my confidence in implementing things increasing week on week. Once I did implement this, I was able to see what the young people identified as feeling at the start of each session (see Figure 1). This was then compared with the activities done in session and the discussions that the group took part in. This comparison highlighted that tiredness had an impact upon their engagement during the sessions. By recognising how the sessions were fitting into their lives, I was able to build a picture of participation for the young people and shape the project according to what the young people were saying through the different avenues of communication. Moving forward I aimed to hold less sessions after school and more out of term time.

(Figure 1) Check in responses from participants

Chart 1 (left) – Post School; Chart 2 (right) – School Holidays

As I have a background in professional photography, I initially intended on using visual and creative methods with the young people, as they are also widely acknowledged for their ability to give voice when working with marginalised groups. Interestingly, in this project, these creative techniques have not enabled the young people to have multi voiced opportunities of expression, rather limited their outcomes to ones suggested by the adult researcher. So far, creative methods have provided less opportunity for the young people to express their lived experience than the more traditional qualitative method of informal focus groups. When comparing a photo elicitation exercise that the adult researcher directed, with a focus group that was led by discussions decided upon by the young people, I was clearly able to identify where the participation was enabling the voices of the young people to be elevated and how when driven by an adult agenda it was almost discouraging the expression of the young people. Consequently, discussions that arose from the focus groups have led on to the potential formation of research questions and progression led by the young people has meant that their ‘parallel project’ of doing something for the community and establishing community events is now leading the research proposal.

At this point I can see how working to understand and illustrate the complexities of research with children and young people, such as the multivoicedness of children and young people’s expressions and interactions, broadens the discussion around how to effectively build a research project that strives to elevate youth voice at every stage. This research is still in the very early stages, and as I am lucky enough to have an opportunity to engage with a group of young people through a longitudinal study, I hope to explore how researchers can further recognise the mulitvoicedness of children and young people engaged in the research process and how researchers can sufficiently respond to the multivoicedness of participation with children and young people.

______________________________________________

*Banner photo by Daniel on Unsplash

*The views expressed in the blog are those of the author alone. They do not reflect the position of the Saw Swee Hock Southeast Asia Centre, nor that of the London School of Economics and Political Science.