It is the sixth day of the UCU strike with staff at 60 universities across the country participating and many more not crossing the digital picket. While academics, unions, and universities have been making headlines, we approach four students, Cara June Michel, Xara Zahibi Dutton, Thomas Cury, and Jennifer Irving to tell it as they see it.

During the ongoing University College Union (UCU) strike that universities such as University College London (UCL) are participating in, the lack of common discourse in the classroom setting and beyond can result in student narratives being muted. We are a group of UCL students who are thinking about our engagement with the strikes and would like to share our experiences – positive, negative, and neutral – about the UCU strike. We interviewed each other to provide some personal perspectives for you to read.

Why are students disengaged from strike action?

TC: I think a lot of it has to do with a lack of understanding of what the strikes are about it and its wider ramifications. In my experience, and over the past few days on the picket line, a lot of students don’t know the answer to basic questions: Why do staff go on strike? What is the significance of strike action? What conditions are staff working under? What even is a picket line? I think this is symptomatic of a wider issue and is no one’s fault as such: there’s a real lack of sense of community in our university. Students often engage with higher education as consumers and individuals; they buy a service and get something in return.

Ultimately, I think this leads to students viewing the strikes as a separate issue unrelated to them, and that they’re just unfortunate to be caught up in the mess. But really our struggles are interconnected: we’re all subject to the ongoing marketisation of the university, which plunges students into mountains of debt and makes university workers’ positions increasingly precarious. Over the past few days, I’ve felt that once students become more conscious of the conditions and struggles of staff – and often these are parallel to what they’re experiencing – they begin to realise the importance of what is going on.

How are students supporting the strike?

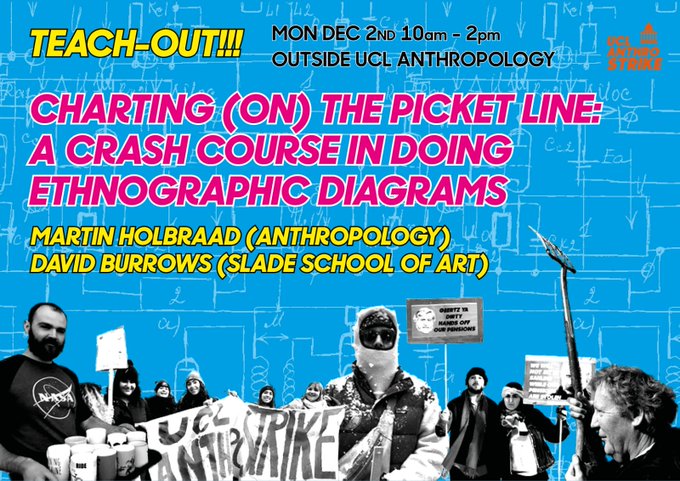

JI: Besides not crossing the picket line, students are making their resistance to the university visible in a number of ways. We have seen a number of students standing on the picket line and helping staff hand out flyers and trying to convince those crossing the picket line to stop. On a practical level standing in visible solidarity is the traditional way to send a message to the university administration. It’s also a great way to spread information and suggest alternative places to study, alternative forms of study. The picket line is not simply a barricade, but a dynamic place and a learning environment and by engaging with others on the picket line and in the concept of the picket line, we are educating ourselves and creating the university as we would like to be a part of. Teach-outs held by lecturers, students and staff are a very practical and literal manifestation of the possibilities of the picket line.

'Why we strike' - a teach-out at one of the UCL picket lines/@fguesnet*

'Why we strike' - a teach-out at one of the UCL picket lines/@fguesnet*

But like most people, this is not always possible to sustain everyday – health or assignment deadlines can get in the way. We are appealing to students to email Michael Arthur, the Provost of UCL: disrupting administration is a great way to directly express your solidarity in the “language of management” as my lecturer once said. It’s quick and easy and gets your voice out there. I have spent time speaking to friends – so many people don’t know what’s going on. Informing myself and others, spreading the word and talking to people about what is happening are valid ways of supporting the strike. I also plan to sign the open letter that will soon be published on our Student Union website.

A picket is not just a line of people, but is an ecosystem and it needs support! One of the ways I have found most personally rewarding to engage in the strike is by providing food for those on the picket lines. Feeding and caring for others can be a radical practice of dissent; this strike is not only concerned with pensions, but also with increasing workloads in conjunction with the casualisation of work and zero hour contracts. I think it’s important on a practical level not to make the picket a place of martyrdom and unnecessary suffering. We need to care for our teachers and ourselves in a university that is constantly trying to pit us against each other and treat our relationships as transactional. These are miserable rainy days with an increasingly bleak sense of the future. Approaching the strike as an opportunity to practice care and show solidarity with your lecturers is one of the best ways you can directly engage.

Striking and picketing aren’t easy or comfortable experiences. What has been difficult about maintaining picket lines?

XZD: The breakdown of daily structures and routines can be a real challenge. Not having a framework for your day, but still having work presents challenges to personal discipline. The breakdown of communities and routines of contact with friends and peers can also be challenging; given the fragmentation of our campus, lectures and seminars can be some of the only spaces which bring students together. Engaging with teach-outs can help to alleviate this feeling of isolation. The Institute of Education (IOE) and the Anthropology and English departments have been particularly active in organising teach-outs.

A teach-out flyer/@cagsgaraway*

A teach-out flyer/@cagsgaraway*

The breakdown of our daily routines mean we tread different pathways, which lead us to interact with our physical and social environment in new ways: interdepartmental contact is made. Contact which breaks down pedagogical hierarchies is made. Academic staff, non-academic staff, and students at UCL interface in ways which they simply couldn’t otherwise. This enmeshment is carried forward, at least in spirit, when strikes end. Missing lectures, seminars, and tutorials because of strike action isn’t simply a case of delighting at the extra time freed to spend in bed; UCL students and teachers would prefer to be in the classroom, engaged in the learning process. But the strikes also present opportunities to reflect on personal learning practices. Students have been encouraged to find alternative learning resources and study spaces, and hold peer-led seminars off campus (hint: for off-campus study-spaces try Senate House, The British Library, Friends House, The Wellcome Trust, SOAS Library and SOAS JCR). Adapting to impromptu learning circumstances provides experience that can be used to transform our personal learning practices for good.

It’s important to recognise as well that getting involved in picketing is particularly difficult for disabled individuals. Some students and members of staff have drawn particular attention to the need to communicate more clearly about the accessibility of picket lines. The IOE contains the only bathroom on campus that a paraplegic student or member of staff can use. The IOE therefore holds the only fully accessible picket line on campus. Learning about the need to think more about the accessibility of picket lines has been important. It has made it clear that there’s still a lot of work to do in making sure everyone’s voice is heard and integrated in this struggle. Beginning to have these conversations as we organise has made visible the daily accessibility limitations that UCL staff and students encounter everyday, and has provided a much-needed prompt to improve our consideration of the needs of all members of the UCL community.

What have you learned from being at the picket lines?

CJM: In both this as well as last year’s strikes, I have been visiting picket lines across the UCL campus. Despite working up to a few deadlines as part of my final year, I have not regretted attending teach-outs and other events. Being at university does not need to be solely about the courses we attend. Beyond the confinement of tightly scheduled lectures and busy tutorials, supporting the strikes gives you a rare chance to converse with professors — as well as put into practice some of the abstract things you theorise about in class, for instance decolonising the way we teach and learn. Or, to (somewhat reluctantly) reference Bourdieu’s practice theory, only through repeated bottom-up action can the university system be resisted — a system that leaves a lot to wish for not just for staff, but also for students.

The strikes have given me a glimpse of the possibility of a different university life. As ever-so-implicit hierarchies dissolved, a sense of community emerged.

The things I gained are invaluable to me. From lecturers’ kids running around to a respected professor gardening, the strikes have given me a glimpse of the possibility of a different university life. As ever-so-implicit hierarchies dissolved, a sense of community emerged. When I next encounter one of the many moments when I feel isolated at university or not supported in my studies, I will call to mind that this sense of community is something we need and can work towards. Ultimately, only jointly can students and staff resist the pressure that university policy places on us to compartmentalise.

We are very grateful to Cara, Xara, Thomas, and Jennifer, who met a very tight deadline for this post despite studies, strikes and everything else. Thanks for your contribution and commitment!

___________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

This post is opinion-based and does not reflect the views of the London School of Economics and Political Science or any of its constituent departments and divisions. __________________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Image info and credits:

Main picture: A teach-out with staff and students on women, LGBT people and the labour movement on the UCL Americas picket line/@joshhollands

‘Why we strike’ teach-out/ @fguesnet

UCU strike Anthropology flyer/ @cagsgaraway

The strike is to fight for the right!